For most Americans, the great day of realization of the seriousness of the COVID-19 threat—or more precisely, the seriousness of the official reaction to it—was Thursday, March 12th, when they woke to the news that the previous evening, the National Basketball Association had postponed an OKC Thunder-Utah Jazz game after a player’s test result came back positive, and then quickly canceled the remainder of the season. I was less concerned with the NBA, but coincidentally, also on Thursday the 12th, was informed that a certain institution of higher education that we all know and love was moving to remote learning for undergraduate and graduate classes for its entire Spring Quarter of 2020. Simultaneously, nearly all students were ordered to plan to vacate their on-campus housing by 5 PM CDT on Sunday, March 22nd.

I had also just returned home from a severely truncated trip to Italy which had gotten no farther than New York City. Had the Italy leg been undertaken, I would have been on one of the last flights out of that country before it was locked down entirely, and would have been a strong candidate for two weeks of quarantine upon arrival in the US. I was therefore necessarily concerned with pandemic response, and on the day after my return home, sent an e-mail to several leaders and volunteers in my church with a general offer of expertise and recommendations to pursue several of the items discussed below, especially a communications plan.

Response was enthusiastic. Church elders formed a response team immediately and began sending communications out to congregants within 24 hours. Text announcements went out on Church Community Builder (CCB), and volunteers quickly produced a short video and uploaded it to the church’s YouTube channel. A technical volunteer quickly created a support e-mail address for communication of needs—or resources—to the response team.

That response team, led by an elder, included the senior pastor, an associate pastor, the facility manager, and interested volunteers. It began to meet weekly, with about half of its membership attending physically and the remainder by online videoconference. I drafted a communications plan, which the leading elder revised and circulated internally. It took the form of a matrix with one row for each item, with columns specifying:

- audiences (congregation, response team, senior leadership, subject-matter experts, all church staff, support volunteers, etc)

- frequency (daily, weekly, “often,” as needed, etc)

- medium (CCB/e-mail, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Zoom, etc)

- creators (specific elder[s], staff members, volunteers, etc)

- typical content (video messages, online meetings, online services, requests for/offers of assistance, action items, latest developments, expectation-setting)

The comm plan also included a roster of content creators, especially the response team itself. Those creators duly produced and transmitted content according to the recommended schedule in the comm plan. One of my first items took the forms of an e-mail and a brief appearance in a video to urge some of the medical adaptations and attitudes described later in this document.

Completeness requires mention of two items which the response team has not yet pursued, as of this writing:

- a skills inventory of the congregation, especially to identify anyone with first-responder or medical training/experience; and

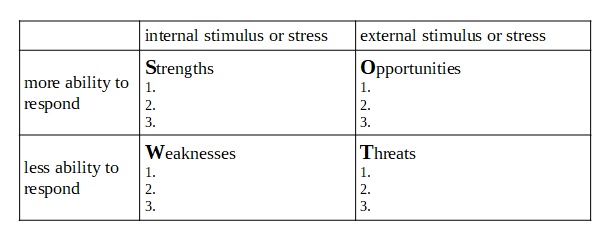

- a SWOT analysis for the church, which might look something like this …

Several weeks later, when state and local guidelines began to be relaxed, a church elder developed and published (via CCB) a “Post-Coronavirus Survey” to query the congregation on their opinions about the church’s actions during the pandemic and when they might be willing to resume in-person meetings and regular Sunday services. Responses exhibited a full range of reactions, from complete unwillingness to attend any function before sometime in July to insistence that the church reopen immediately.

While Federal guidelines literally fit on a (large) postcard, mailed to 138 million addresses in late March, in Missouri, Governor Parson issued a “Stay Home Missouri” Order effective Monday, April 6th, initially to run through Friday, April 24th, and revised several times thereafter. It was two and a fraction pages, single-spaced; a revision on Thursday, April 16th, and the “Show Me Strong Recovery Order” of Monday, April 27th and its revision of Thursday, May 28th added another six single-spaced pages to this. Missouri’s restrictions were noticeably less comprehensive than those of many other states, but still formidable, and ran through June 15th. On Thursday, June 11th, Parson announced that all businesses could fully reopen with the beginning of “Phase 2” on Tuesday, June 16th, but that local restrictions remain in effect.

In Kansas City, the mayor’s office issued a State of Emergency proclamation on Monday, March 16th, prohibiting gatherings of more than 10 people. This was followed by a series of “Amended Order[s],” the first of which was issued on Saturday, March 21st, and effective Tuesday, March 24th, which effectively precluded in-person church services prior to Sunday, May 31st. One such order was aggressively misinterpreted by a lawyer in Orlando to require churches to turn over membership rolls to the city government, which set off a nationwide reaction in social media and required an explicit denial of any such requirement in the next revision.

Fortuitously, the church has a congregant who works in the mayor’s office as an aide, and who spoke at a special prayer meeting at the church on Tuesday, May 5th, which was shown live on YouTube. Like all other events at the church between the Sundays of March 15th and June 7th, it was limited to a handful of people onsite and viewed remotely by anywhere from 50 to 200 people at a time.

As of this writing, the “Fourth Amended Proclamation Declaring a State of Emergency,” issued Thursday, August 13th, and running to three pages of single-spaced text, has no occupancy limit for religious services but requires masks for all indoor public accommodations. It is to remain in effect through Friday, January 15th, 2021.

“All disasters are local”—this admonition from an acquaintance who works in emergency management for the KCPD nicely encapsulates what should guide a church’s response to COVID-19: local conditions. In particular, the vastly elevated (and thankfully unique) death rate in the New York City metropolitan area skews US national statistics. Even within Missouri, as of this writing there have been 200 deaths in the KC-area counties, but nearly 1,000 in the St Louis-area counties, which have only 2/3 more population, for a per capita death rate 3 times higher. The case fatality rate (CFR) for the Missouri side of the KC metro is, so far, 1.7%.

Per capita mortality from COVID-19 in the KC metro overall as of mid-August is ~21 per 100,000, modestly greater than that of the heat wave of 1980, but spread over four months rather than concentrated into three weeks. (Historical note: it was 580 per 100k for the Kansas Flu of 1918.) The relevant medical resources, that is, for the entire metro area, are ~6,000 hospital beds and ~700 ICU beds. The outbreak would have to be many times worse to seriously strain those resources.

But even for metro areas rather than states, aggregate infection levels can be misleading, so church response teams—and they should make decisions as a team—would be well advised to base their decisions on how to manage risks on the very highest-resolution data available. A brief search finds that case counts are far from equally distributed demographically. Data from the KCMO city government show that crude case rates are nearly 2 ½ times higher for blacks than whites, and Hispanics are at 3x the risk of the general population. Notoriously, a very large share, approaching half, of all deaths in the vast majority of jurisdictions nationwide, have been of residents of nursing homes.

These disparities can manifest geographically in striking fashion. The KCMO data indicate that ZIP codes 64123/4, just northeast of the church—and in which many of our congregants live—have COVID-19 case rates exceeding 3,000 per 100,000 of population. They also have median household incomes in the range $27,000-$37,000 per year. For comparison, my ZIP code has a case rate around 700 per 100k and median household income of nearly $50,000 per year. Other ZIP codes in less densely-populated (and even more affluent) areas of the city are all but untouched by the disease.

The overall span of per capita differences can reach two full orders of magnitude. It is therefore shockingly likely that suburban/exurban churches exist where a congregation of 1,000 has experienced, at most, a handful of mild cases, while an urban congregation of 100 has had tens of mild cases, several severe cases, and one or more fatalities. A hair-raising example of this occurred at a church conference in the Quindaro neighborhood (ZIP code 66104; 77% nonwhite, MHI $38,000) of Kansas City, Kansas, in March; of 150-200 attendees, there were 51 symptomatic cases of the disease and 7 deaths.

The risk to be managed by my church—and any other church with a significant urban ministry—is therefore contact with, and among, high-risk individuals, who are nearly always some combination of ethnic/racial minorities, elderly, and low-income. Anyone in regular contact, which is to say oftener than biweekly, with any high-risk person must themselves take precautions to avoid transmitting the disease to their vulnerable friends and relatives.

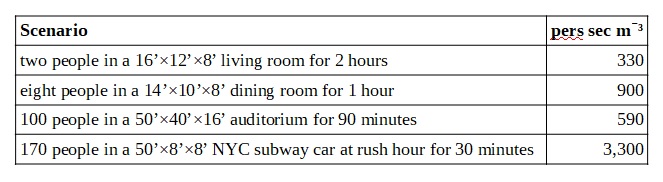

Any large group meeting indoors poses some risk, which varies widely by the number of people present and room size. Without factoring in individual susceptibility or air circulation, consider the number of person-seconds per cubic meter in the following situations:

The specificity of the third scenario above is due to its resemblance to an average service at my church. The second scenario modestly resembles a small group Bible study. The fourth scenario is the grim math behind the deaths in the NYC metro, one-third of all mortality from COVID-19 in the entire US to date.

The number of possible conversations in a group of people goes up as the square of their number—the formula is C = N × (N 1) —so the average church service can easily facilitate a hundred times as many encounters between people as a small-group meeting. This reinforces the need for caution among those who might subsequently encounter vulnerable people as part of their weekly routine.

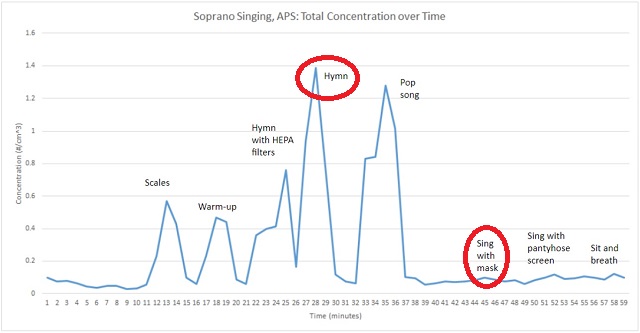

Group singing as a disease vector was made infamous by the Skagit Valley Chorale rehearsal in a church north of Seattle in March, which became a “super-spreader” event in spite of liberal use of hand sanitizer and good social-distancing practices. A webinar in early May put on by the National Association of Teachers of Singing and the American Choral Director’s Association, among others, became well-known in church circles for elucidating the medical dangers of even relatively small indoor performances. The deep breathing associated with singing is unpleasantly effective at both distributing the “respirable fraction” of aerosol particles < 5 μm in diameter and depositing it deep in the lungs. Fortunately, this can be tracked, as explained below, by taking COâ‚‚ levels as a proxy for viral load.

And even more fortunately, it can be greatly reduced by wearing masks.

Churches should of course encourage good individual behaviors, especially by their own staff and volunteers: the combination of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) which has already been massively promoted—handwashing, masks, social distancing—and, arguably, the quasi-pharmaceutical intervention of taking vitamin D supplements. But again, urgency varies drastically with demographics. Middle-class congregations with few members from, or little interaction with, low-income areas and ethnic/racial minorities are ten to a hundred times less likely to experience or cause a significant outbreak of COVID-19.

New Life CityChurch (NLCC) is situated in the East Crossroads neighborhood, just south of the downtown freeway loop in Kansas City, Missouri. The area immediately to its east, reaching from the Blue River to within one mile of the church, is among the most impoverished and uneducated urban environments in the US; in late 2013, the Washington Post’s “Super Zips” webpage, which ranked ZIP codes by MHI and percentage of adults with college degrees, placed 64126/7/8 in the very bottom 1% of the country. It is no coincidence that they are among the most affected by COVID-19 now. NLCC’s response has therefore been driven by both a general willingness to cooperate with local government guidelines and the specific exigencies of its geography.

At NLCC’s final in-person Sunday services on March 15th, and again from resumption on June 7th, volunteers cleaned all “high-touch” surfaces frequently. They also minimized the number of such surfaces by propping most doors open and manning a coffee-serving station rather than allowing attendees to get their own coffee and thereby touching numerous items. There were no printed bulletins or other handouts (there is, inevitably, a phone app for transmission of such information); and no communion ceremony at the end of services. On June 7th, and every Sunday since, they have worn masks as well. Mask compliance in the congregation looks to be ~95%, based on my own observations and reports from others on the response team.

Rated capacity of the auditorium, as it is called (prior to the pandemic, the building was also heavily used as an event space), at NLCC is 195 persons; again, current KCMO orders do not restrict this. Recently purchased seats, larger and more comfortable than their predecessors, effectively limit capacity to ~140, and socially-distanced seating by household cuts this roughly in half. A modification to the church website allowed would-be attendees to reserve seats. The actual maximum number of persons present in the auditorium at any one moment since early June has been ~70, in an area of ~2,000 ft ² and a volume exceeding 30,000 ft ³ (~900 m ³); for a 90-minute service, this would be a rating of ~420 in the units suggested earlier, not much more than the two-people-watching-a-movie-at-home scenario.

Beyond relatively passive measures, however, NLCC is pursuing active air purification in the form of bipolar ionization. Devices installed in the HVAC return vents create oxygen ions which react with cell membranes and viral envelopes to inactivate nearly all microbes passing through them within minutes. Aerosol droplets with ions attached to them are easily caught in filters.

As of this writing, both return vents leading out of the NLCC auditorium have been fitted with bipolar ionizers sourced through a vendor contact. Fortunately the devices were in stock, that is, onshore; demand is heavy and continued supply is fraught with uncertainty, the current manufacturer being Chinese. Installation of four more devices to cover the rest of the building, including the children’s area, offices and conference rooms, and a wedding chapel, is imminent. All HVAC filters have been replaced (for the first time in … a while) and a schedule/budget is in development to do so frequently with the highest-quality HEPA filters that are readily available. Total cost for parts and labor will be $~3,000 for the entire facility of ~7,500 ft ²; the bipolar ionizers require no replacement parts, but regular filter changes will add noticeable operating expense.

This is not a silver bullet. The devices only work when the HVAC fans are running, so those fans must be run continuously on Sunday mornings and during any other high-occupancy periods. That, in turn, affects sound quality in the auditorium, especially during the sermon, and will modestly increase NLCC’s electricity bill.

While it is not possible to directly measure the quantity of viruses being shed by a group of people, it is reasonably well-established that for COVID-19, the predominant mechanism of transmission is through aerosols exhaled by infectious people and inhaled by others. Since people also exhale carbon dioxide, and COâ‚‚ detectors are readily available, after becoming aware of this proxy, I obtained an appropriate device; here are the results from the auditorium for the morning of Sunday, June 14th, our most heavily attended services to date:

The COâ‚‚ level gradually increased as congregants entered the auditorium. The service started with singing at 9 AM, which caused a noticeable rise, with a modest peak about half an hour later. The second service began at 10:45 and showed another, sharper increase over its first twenty minutes. Concentrations never approached a threshold of concern—very generally, 1000 ppm, although the detector will sound a subtle alarm, like a metronome ticking faintly, at 800.

Overall the effect was quite moderate and indicative of relatively low risk of disease transmission. A major reason for this, however, is an unusual feature of the auditorium: it has two glassed-in garage doors, 8′ wide and 7′ tall, facing the street, which can be, and were, kept open for the duration of both services (to minimize the effect of this on its measurements, the COâ‚‚ detector was in a back corner, across the length of the room, > 50′ from them). This greatly improved airflow around and through the room. What the detector will read on Sundays when it is too hot or too cold to have the garage doors open is among the unknowns.

Church leaders have not chosen to reduce the usual amount of singing in a service, and since outdoor transmission of the disease seems to be minimal, as long as the garage doors can be opened, especially in combination with bipolar ionization and mask-wearing, this decision appears justified.

By far the most important resource for meeting the challenge of a novel viral pandemic, or any other seemingly unprecedented disruption, is attitude. Eric Hoffer famously wrote: “In a time of drastic change it is the learners who inherit the future. The learned usually find themselves equipped to live in a world that no longer exists.” So there is a sense in which everything has to be on the table.

The commitment to learning itself, however, is a constant principle, and since NLCC is a church, after all, it has other constant principles to bear in mind and to help form its response:

- The greatest reward in the Beatitudes is reserved for “peacemakers” (Matthew 5:9), and a beautiful figure of speech in the RSV translation of Zechariah 11:7 speaks of shepherd’s staffs named Grace and Union; fittingly consoling images in a time of great national discord.

- An entire chapter in the Pauline epistles is about exhibiting mutual respect through individual conduct—over, as it happens, matters of perceived contamination (Romans 14)—while a famous paragraph in another models finding common ground with all kinds of people (1 Corinthians 9:19-23).

- On a more cautionary note, in a fraught legal/regulatory environment and a time of division, some of the greatest hazards may be posed—at least in the current American context—by fellow believers (Mark 13:9, 11-13; Matthew 10:17-22; Luke 12:11-12).

NLCC’s elders and staff have repeatedly conveyed, through videos, e-mails, and sermons, that all are welcome, that no political litmus tests are being applied, and that the church is striving to both cooperate with local authorities and pursue its mission as normally as possible, encouraging its members to model good behavior and “live peaceably with all” (Romans 12:18).

The wider society seems to be struggling to adopt appropriate risk-management strategies. Political debate is often presented as a stark choice between pure risk avoidance and pure risk acceptance, which for the church would mean either no gatherings at all or doing things that might well endanger congregants—or vulnerable people they might visit. Far better to pursue direct risk mitigation, as with air purification/monitoring, sanitizing, masking, social distancing, etc, or risk transfer, by continuing to offer online alternatives to physical presence, reassuring anyone who feels unsafe in a room with too many others that they can still be a valued member.

NLCC is, in most ways, managing its COVID-19 risk well, although we have a ways to go before we are back to anything like our situation at the beginning of this year. Ongoing and imminent issues include:

- persistent need to reiterate the messages of Romans 14 and 1 Corinthians 9:19-23

- general stress on congregants and volunteers

- temporary—I hope—loss of congregants and volunteers on both sides of the perceived-risk spectrum, that is, 1) self-identified high-risk people afraid to attend in person … and 2) people refusing to follow public-health directives from the mayor’s office, that is, anti-maskers

- imminent likelihood of congregants and volunteers testing positive and needing to both self-isolate and provide reports in support of contact tracing

- imminent likelihood of controversy over the annual flu vaccine this autumn

- imminent likelihood of controversy over the much higher rate of COVID-19 infections, serious cases, and deaths among racial/ethnic minorities

- physical discomfort in the auditorium over the winter if we continue to operate with garage doors open during high-occupancy periods

- possible capacity restriction on religious gatherings by the mayor’s office (we already plan to go to three services plus overflow rooms on Sunday mornings to compensate)

- likelihood of controversy over an eventual COVID-19 vaccine

Future challenges deriving from the pandemic are already well within the horizon. Millions of Americans are unemployed, disproportionately among lower-income, hourly workers. A rapid, but partial, economic recovery is underway, and the altered post-pandemic preferences of the most, and least, vulnerable will have massive economic and cultural effects. Full recovery may take several years, and church attendance and involvement may slip noticeably, with believers culturally marginalized and congregations far smaller—but comprised of relatively fervent, active members.

Education is being massively disrupted at every level. On any given weekday from mid-March to late May, half of the schoolchildren in the KC metro were disengaged from any form of schoolwork, neither attending online nor involved in homeschooling. Operation of school districts and institutions of higher education this autumn is deeply uncertain, largely due to age-related risks posed by the disease to the most senior (and therefore powerful) administrators, professors, and teachers. Few if any local school districts are starting classes until after Labor Day, or holding classes in person until various criteria for bringing the pandemic under control have been deemed to be met—which could mean by late September, but in practice means indefinitely. The sharp risk avoidance/risk acceptance dichotomy mentioned above is not helpful in this regard; the CDC’s heavily risk-avoidance-oriented guidelines to schools would drastically reduce their capacity.

A large plurality, if not an actual majority, of victims of COVID-19 are in nursing homes, raising the prospect of a de facto policy of euthanasia of the unwanted elderly. Pro-life organizations have warned of such a possibility for decades. Whether they will resist its manifestation remains to be seen. A search of both the Kansans for Life and Missouri Right to Life websites, however, finds no such response.

The wider church’s influence on American society may be attenuated by its association with the promulgation of an array of discordant, mean-spirited conspiracy theories. It is already common to hear that this or that political officeholder deliberately acted to make the pandemic worse, if not cause it altogether (and that the removal of this or that officeholder will thereby fix the problem), or that this or that billionaire is plotting or promoting some opportunistic wickedness to be attempted in the near future (followed by placing this or that billionaire’s name in nomination for the Antichrist). The reality that they’re all groping in the dark like everyone else is the reason for Paul’s admonition at the beginning of 1 Timothy 2.

The wider church can keep from shooting itself in the foot by following some do’s and don’ts:

- be steadfast (James 1:2-4, 12)

- have a servant attitude (Philippians 2:3-7)

- as part of that steadfastness and service, remember to regard the most vulnerable in prayer and action—homeless shelters, nursing homes, prisons—being cognizant of the ultimate unity of believers (Romans 14:7)

- do not endanger vulnerable people through carelessness or selfishness (Isaiah 42:3)

- do not promote distrust in public health organizations (1 Peter 2:13a) … including by promoting New Age “alt-med” home remedies

- do not promote unproductive arguments and controversies, and shun repeat offenders (1 Timothy 6:4; 2 Timothy 2:23; Titus 3:9-11)

On that last point, my experience with such people is that they are strikingly likely to display the precise behavior described in Proverbs 29:9.

Understandable resentment over China’s handling of the early stages of the pandemic, possibly including months of cover-up and certainly including weeks of misdirection, threatens to join other, equally understandable resentments over official Chinese policies (suppression of religious minorities, the crackdown on Hong Kong, etc) to coalesce into a full-blown casus belli. Both China and the US are now led by a generation with no lived experience of the last global crisis during the 1920s-1940s—in China, Japanese occupation and civil war; in the US, the Great Depression and World War II. Geopolitical risks are thereby heightened, especially US-China tensions, and if Xenakis’ “58-year hypothesis” holds, this very year will see an echo of the Cuban Missile Crisis. In this context, peacemakers may be needed as never before in the lifetimes of anyone younger than 75.

Quantitative risk analysis is hard, or at least frequently counterintuitive. But if it has any significant lifesaving ability, everyone capable of doing so must attempt it. Properly pursued, it will guide action toward effective strategies—and away from ineffective ones. Urban churches, in particular, face difficult choices to reconfigure themselves and adopt safety measures which can have nontrivial costs that become a serious draw-down on already-scarce resources. Nonetheless, they and the suburban/exurban and rural churches far less directly threatened by COVID-19 should be working toward full reopening as soon as possible. The difficulty is, of course, massive negative publicity in the event of identification as the host of a “super-spreader” event; this is the likely reason why the largest church in the Kansas City metro has repeatedly delayed resumption of in-person services and is even planning to abandon its traditional Christmas activities. A $100 million facility (I worked on that project as a volunteer IT project manager) might as well be Urakami Cathedral 75 years ago this month for what the reaction to COVID-19 has done to its operations. Without significant reprioritization and commitment, many churches, even the seemingly most resourceful, will become dormant.

Envoi:

This is a revised and updated version of a document I prepared in June to advise Living Water Christian Church in Parkville, Missouri. I have published a more detailed and rigorous account on LinkedIn.

I explicitly acknowledge our very own “Dan from Madison” for his assistance in acquiring bipolar ionizers.

No effort I have undertaken since my involuntary semi-retirement four and a half years ago has given me greater satisfaction or a more profound sense of gratitude for my current situation and the resources available to me.

One small point. The Commie flu was found in the sewers of Venice, in December of last year. :https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53106444

The Chinese always claimed it came from outside, perhaps they have a point.

this assumes that someone taking no measures is behaving in an “unsafe” manner … that is a fallacy … for 99% of the population safety requires no measures …

I recommend reading Alex Berenson’s pamphlets on SARS CoV-2 and COVID-19. In the 2nd one, he goes over the fact that not even in the worse-case scenario for a pandemic did the CDC have a lockdown as a response to outbreak–this based on the science. https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B08F7W9276/ref=dbs_a_def_rwt_hsch_vapi_tkin_p1_i0

}}} The fourth scenario is the grim math behind the deaths in the NYC metro, one-third of all mortality from COVID-19 in the entire US to date.

I really doubt it’s as much as you might think. It’s more relevant to most other high-density areas than it is to NYC.

If it were, then NYC would not be the center of it all, other high-density places — Chicago, LA, Boston, etc., would be similarly bad, instead of just “bad” (Chicago, Philly, LA, Detroit are hotbeds, but not on the level that NYC is.

The numbers have certainly changed somewhat, but early on, when the NY area represented 2/3rds of the fatalities, the Johns Hopkins “worst 20 counties”, there were five counties — LA, Cook (Chicago), the one Philly is in, and the one Detroit is in along with one adjacent to Detroit. The other 15 counties all surrounded NYC, and were either NYC, adjacent to NYC, or adjacent to one of THOSE. The only “exception” was Hartford (CT) county, which, clearly, also interacted with NYC a lot. These still remain high fatality areas.

It should also be noted that of the above “worst 20 counties”, every single one had enacted a statewide policy demanding that Nursing Homes take in the CV-exposed, despite the fact that this clearly exposed one of the most vulnerable populations from the very start (Again, “Dated stat”, but at one point, if not still, fully 62% of all fatalities were people in Nursing Homes).

Even the elevation of Miami, FL (Dade County), into that “hardest hit” list, that’s THE most common place for old people to be in FL, as a mecca for retirement.

I will point out, the MEDIAN age of a CV fatality in the USA is 75 or so.

Meanwhile, the LIFE EXPECTANCY of people in the USA is 75-82 depending on State of residence, and only three are 81-82, with 13 @ 75-76.

So, while any death is a personal tragedy, CV really really isn’t actually increasing overall risk much… It’s really just becoming one of those “The bullet that gets you.” things, like accidental falls or cancer. You do what you can to reduce your personal risk and Get the Eph On With Life.

One specific issue NYC has is its extreme dependence on public transit, especially the subway.

And they made the situation worse than it needed to be by shortening the train lengths and thereby increasing the packing of people.

I think that Jay’s program is very well thought out and really hope it turns out to be effective. It beats anything that I’ve heard of so far.

It stands in stark contrast to the actions of the supposedly “professional” safety head at my work place. His total precautions to date have consisted of supplying a Chinese infra-red thermometer and a big stack of questionnaires that we all have to fill out every day. The Chinese thermometer came with a “certificate” on a small slip of paper wholly in Chinese. This in a place where everything else we use has to have a properly documented traceability to NIST standards.

The temperature and humidity traces of your CO2 detector are suspiciously flat. If your HVAC system is that good, even with big doors open, you have a true gem. Otherwise, it’s probably in a more or less stagnant area. The normal place to sample is the return duct.

I don’t quite understand the chart on singing. Was the trace an actual count of true particles or based on CO2? If it was CO2, I don’t believe wearing a mask would change the concentration. I accept that CO2 is probably the only practical proxy for how “used” the air is. Measuring actual particles would be very difficult and expensive and impossible to do in real time. It’s certainly plausible that deep breathing coupled with projection would increase infection.

The how do I make money question seems to consist of trying to sell me various skin temperature monitoring systems. The winner so far cost about $20K. I got an offer for hand sanitizer for $0.50 an ounce, no word on whether or not it is also toxic. Lex’s idea about approaching the problem from that direction in the other thread may give a place to start but it isn’t likely to yield a good answer when the people buying are operating on some combination of panic, ignorance and conformity.

If there had only been some sort of government agency charged with determining how disease was spread and how it could be controlled in the real world. Instead, we have to make it up as we go along, based on hunches, surmise and conjecture.

As I said, much better than anything else I’ve seen, I’ll have to see how I can use it.

Thanks, Jay.