In Thomas Pynchon’s novel Gravity’s Rainbow, one of the characters explains a ‘European-style gangster hit’, which he says consists of three shots: head, heart, and stomach. Yes, that should definitely ensure the target’s demise.

It struck me that this comprehensive approach to high-certainty murder provides a pretty good analogy for some of the malign happenings in America and in many other Western nations, and I wrote a post on that theme last year. In my analogy, ‘stomach’ represents the basic, essential physical infrastructure of society–energy and food supply, in particular. ‘Head’ represents the society’s aggregate thought processes: how decisions are made, how truth is distinguished from falsehood. And ‘heart’ represents the society’s spirit: how people feel about their fellow citizens, their families, friends, and associates, and their overall society.

Over recent years, all of these things are under assault…and, given that 2024 is an election year, I think it’s fair to note that the ideology of the Democratic Party is a major factor in driving all of these malign trends.

Stomach: The suicidal energy policies of Germany could serve as a poster child here, but similar trends are in place in other countries, although mostly not so far along. (The US state of California seems to want to be next on the list of bad examples.) The destructive farming policies of Sri Lanka, implemented with the enthusiastic cheerleading of Western experts, now have echoes in Canada and in the Netherlands. And energy and agriculture are of course closely coupled…for the production of fertilizer, for the operation of farm equipment, and for the transportation of supplies to the farms and the transportation of agricultural products to process and distribution centers and ultimately to consumers.

Nearly all physical goods and products come ultimately from farms or from mines. At least in the US and in much of Europe, regulations and litigation have made it very difficult to open new mines and even to keep existing ones in operation. Yet there are very extensive materials requirements for the wind, solar, and battery systems required for the envisaged ‘energy transition’…and the answer, if one asks where these materials should come from, seems to be only ‘not from here.’

Pressuring people and entire economies for maximum use of wind and solar…while at the same time amping up the difficulties and disrespect facing the people and companies involved in the extraction and processing of the necessary materials…is a sure recipe for shortages and Greenflation.

Speaking of disrespect, the American businessman and politician Michael Bloomberg, has made some rather remarkable assertions about both farming and manufacturing. With regard to farming, he said:

“I could teach anybody, even people in this room, no offense intended, to be a farmer,” Bloomberg told the audience at the Distinguished Speakers Series at the University of Oxford Saïd Business School. “It’s a process. You dig a hole, you put a seed in, you put dirt on top, add water, up comes the corn.”

…and regarding manufacturing:

“You put the piece of metal on the lathe, you turn the crank in the direction of the arrow and you can have a job. And we created a lot of jobs.”

All of which elides the vast array of knowledge and skills required in order to do either farming or manufacturing successfully. I doubt that Bloomberg, for all his knowledge of information technology and finance, has much comprehension of any of these areas. What he projects here is a feeling of contempt for people who are involved in the physical world rather than his own symbolic world of information technology and media.

Journalists and politicians, in particular, seem to have little grasp of those essential technologies, which I have metaphorically classified under ‘stomach’, even at the most fundamental levels. And too many political leaders think…even while preaching about their respect for Science, that they can ignore people with actual, practical experience with energy and the other technologies which they wish to control. For example:

Trudeau’s green hydrogen announcement, as big an international energy policy statement as there has been in memory, was held far from Canada’s energy heartland, and included no one from the energy sector that is currently shouldering the load.

Not only were they not invited, but Trudeau went out of his way to make an absurd statement about the lack of an economic case for LNG that was akin to a drama teacher going on stage at the Detroit Auto Show and telling the audience to get rid of all their wrenches because he didn’t think they were needed anymore.

Head: The cognitive methods that have made Western societies thrive are under assault. Such benign things as asking students to get the right answer and to show their work are denounced as racism. Debate and discussion have become difficult as disagreement is often perceived as a threat. In law, the adversary system itself is under attack as lawyers are pressured not to represent unpopular clients…something that has long been the case in totalitarian nations and in areas dominated by mobs and by lynch law.

A vital part of the toolkit that has driven progress–social progress as well as technological progress–has been the open discussion enabled by the spirit of free speech. This is under severe attack, not least on university campuses. A recent Quillette article provides multiple data points on campus hostility to allowing speakers whose view might offend somebody. Link A 2017 study, based on a sampling of all US registered voters, shows that 30% of Americans favor banning speakers “if the guest’s words are considered to be hateful or offensive by some.” Among Democrats–and professors and administrators are much more likely to be Democrats than to be Republicans–the corresponding number is 40%. And for Democrat women–a demographic which is in the ascendency in key roles on campus–the opposition to free speech, as measured by the above question, is 47%. Link Not a hopeful sign for the future of campus free speech or for the direction that American society will evolve as students who have come of age in its universities move out into the wider world.

In science, ideas and conclusions which conflict with established views and prestigious people are increasingly likely to be condemned and suppressed as ‘misinformation.’ This paper Link argues persuasively that identity politics and censorship go hand in hand. Major scientific publications are now evaluating submitted papers based on (what someone thinks are) the moral implications of the proposed conclusions, not just on the truth or falsity of those conclusions–see Alex Tabarrok’s recent post as well as this Quillette article.

There are of course precedents for this kind of thing. As the blogger Neo notes, “The Soviets actively squelched science that contradicted certain political messages they wished to get across.” The agricultural catastrophe that was brought about by the nonsensical but politically-correct and politically-enforced theories of Lysenko is well-documented history, but the damage is much broader than that. This article mentions that the Soviets at one point banned resonance theory, in chemistry, as “bourgeois pseudoscience.” The field of cybernetics–feedback systems and automatic control–was at one point denounced as “a misanthropic pseudo-theory”, among other things. (It is interesting to note that “few of these critics had any access to primary sources on cybernetics”…the denunciations were largely based on other Soviet anti-cybernetics sources.)

In Arthur Koestler’s novel Darkness at Noon, protagonist Rubashov is an Old Bolshevik who has been arrested by the Stalinist regime. The book represents his musings while awaiting trial and likely execution.

A short time ago, our leading agriculturalist, B., was shot with thirty of his collaborators because he maintained the opinion that nitrate artificial manure was superior to potash. No. 1 is all for potash; therefore B. and the thirty had to be liquidated as saboteurs. In a nationally centralized agriculture, the alternative of nitrate or potash is of enormous importance: it can decide the issue of the next war. If No. 1 was in the right, history will absolve him. If he was wrong…

Note that phrase in a nationally centralized agriculture. When things are centralized, decisions become overwhelmingly important. There will be strong pressure against allowing dissidents to “interfere with” what has been determined to be the One Best Way.

The assault on what I have called “cognitive methods that have made Westerns societies thrive” has not originated only from the universities, but they have been the most influential source of this destructive challenge. Which is ironic, given that the great growth of educational institutions was driven by and premised on the Enlightenment ideals that all too many of these institutions seem focused on negating.

There was once a rather sinister toy: it consisted of a box with a switch on the side. When you turned the switch to on, the box would open, and a hand would come out, and the thing would turn itself off. The behavior of much of western academia seems modeled after the behavior of that box. Unfortunately, it’s not just themselves that these institutions may succeed in turning off.

Read more

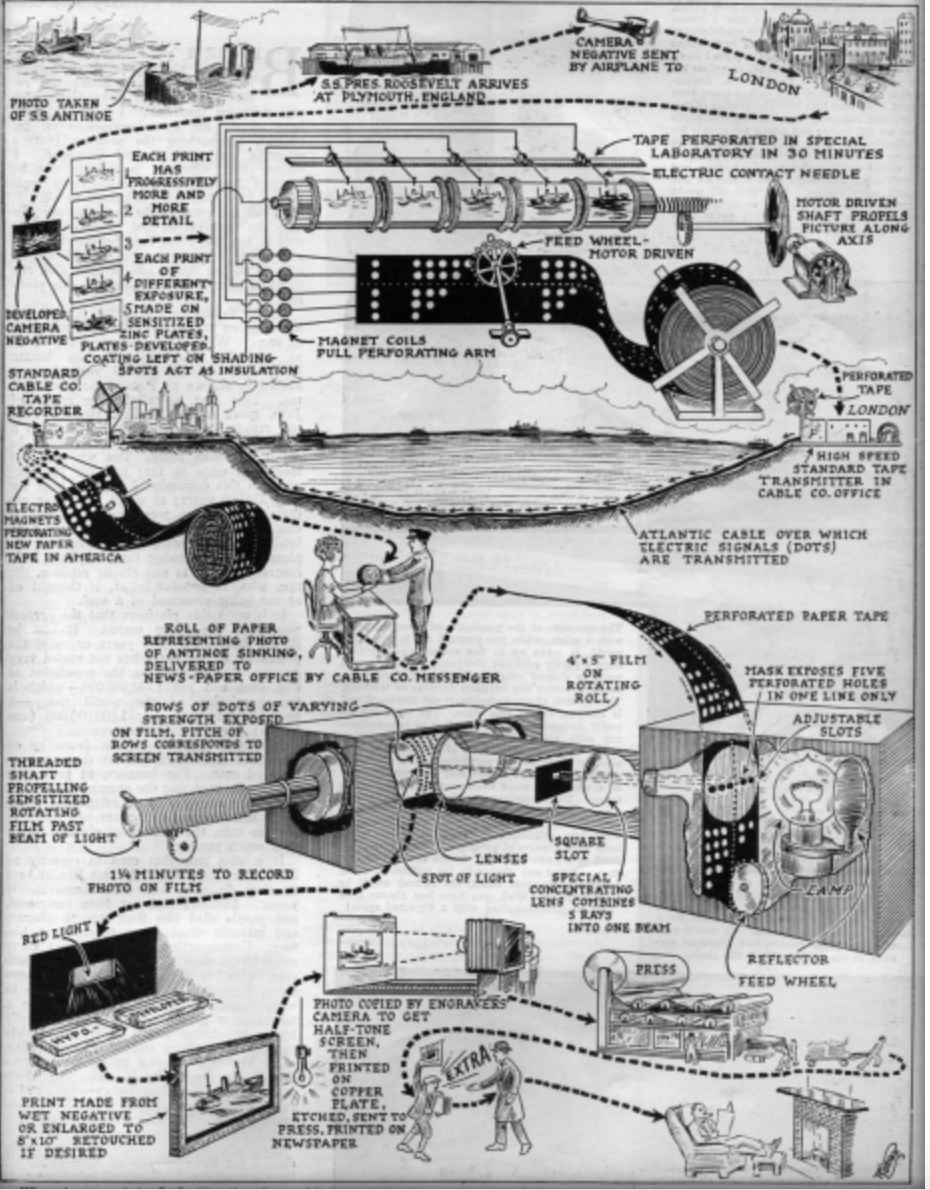

The twenties. An era of Prohibition (and gangsters)…jazz…flappers…The Great Gatsby…and an accelerating stock market. I thought it might be fun to take a look at the state of technology as it stood a century ago, in 1925. This post first post of a series will focus on communications and entertainment..

The twenties. An era of Prohibition (and gangsters)…jazz…flappers…The Great Gatsby…and an accelerating stock market. I thought it might be fun to take a look at the state of technology as it stood a century ago, in 1925. This post first post of a series will focus on communications and entertainment..