[ cross-posted from Zenpundit — Jefferson, economics of possession and ideas, Occupy COG, library ]

1.

Let’s start with Thomas Jefferson. I don’t know if he was the first to mention this curious distinction on record, but he makes the point nicely:

If nature has made any one thing less susceptible than all others of exclusive property, it is the action of the thinking power called an idea, which an individual may exclusively possess as long as he keeps it to himself; but the moment it is divulged, it forces itself into the possession of everyone, and the receiver cannot dispossess himself of it. Its peculiar character, too, is that no one possesses the less, because every other possesses the whole of it. He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me. That ideas should freely spread from one to another over the globe, for the moral and mutual instruction of man, and improvement of his condition, seems to have been peculiarly and benevolently designed by nature, when she made them, like fire, expansible over all space, without lessening their density at any point, and like the air in which we breathe, move, and have our physical being, incapable of confinement or exclusive appropriation. Inventions then cannot, in nature, be a subject of property.

John Perry Barlow quotes that gobbit of Jefferson as the epigraph to his essay, The Economy of Ideas.

2.

Here’s Lawrence Lessig, in his essay Against perpetual copyright:

Tangible goods are rivalrous goods

For one person to gain some tangible item, another person must lose it. For one person to gain the ownership of some piece of land, the previous owner must surrender ownership. T his is the ordinary state of physical property, and the laws around physical property are designed around this fact. Property taxes, zoning laws, and similar legal constructs are examples of how the law relates to physical property.

Intellectual works are non-rivalrous

Intellectual works are ordinarily non-rivalrous. It is possible for someone to teach a work of the mind to another without unlearning it himself. For example, one, or two, or a hundred people can memorize the same poem at the same time. Here the term “work of the mind” refers not to physical items such books or compact discs or DVD’s, but rather to the intangible content those physical objects contain.

3.

As someone whose work falls almost entirely in the “non-rivalrous” category, I am naturally very interested by this distinction, both for my own sake, and because (if the coming economy is an “information” or “imagination” economy) it may be the hinge on which the future of that economy turns…

4.

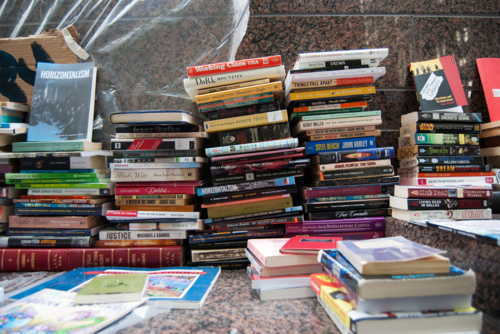

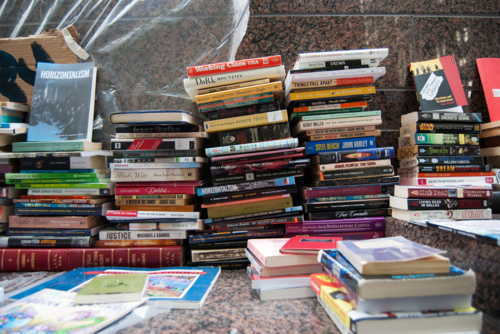

Which brings me to the Occupy movement, and to this curious fact which I found in an article I didn’t otherwise read. It’s from David Graeber, On Playing By The Rules – The Strange Success Of #OccupyWallStreet :

It’s no coincidence that the epicenter of the Wall Street Occupation, and so many others, is an impromptu library: a library being not only a model of an alternative economy, where lending is from a communal pool, at 0% interest, and the currency being lent is knowledge, and the means to understanding.

In quoting this, I mean neither to endorse nor to condemn the movement, but simply to note that its center of gravity as described here (although technically, books are rivalrous goods) falls clearly within the non-rivalrous category: it is a market-place of ideas.

5.

As a one-time tank-thinker, I was trained to spot early indicators.

I don’t know what this one means, but I suspect it’s an indicator. Give me another to pair it with, and I may be able to foresee a trend.

What do you see?

6.

I spotted a copy of Mikhail Bulgakov‘s The Master and Margarita in one of the photos.

photo credit: Blaine O’Neill under a CC BY-NC 2.0 license

and DH Lawrence, Sons and Lovers and Christopher Isherwood, The Berlin Stories; Strindberg, The Plays and Beckett, Krapp’s Last Tape; Dr Who, yeah and Star Wars too; William Gibson‘s Neuromancer and his Mona Lisa Overdrive; Max Marwick‘s Witchcraft and Sorcery; Orson Scott Card‘s Ender’s Game and Lewis Carroll‘s Alice in Wonderland — and for the politics of it all, Marina Sitrin, Horizontalism: Voices of Popular Power in Argentina and Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan, Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict… which I’ve linked for your convenience.

7.

For what it’s worth…

Nathan Schneider‘s article, What ‘diversity of tactics’ really means for Occupy Wall Street, cites Zenpundit blog-friend David Ronfeldt‘s study (with John Arqilla) Swarming & the Future of Conflict — along with (among others) Gene Sharp, whose work I discussed on Zenpundit a few months back.