How to spot high-agency people. Interesting list.

The genealogy of nuclear fear. (Nuclear here referring to nuclear power, not nuclear war.)

A survey cited at LinkedIn: Gen Z (aged 16-25) wants to work in media and entertainment when they grow up. “This generation values things like work-life balance, flexibility and creativity over more traditional values like job security” also, half of this demographic is interested in pursuing entrepreneurship in some way. Here’s a link to the actual survey.

How much ‘work-life balance’ does a successful actor or director really have, though? And entrepreneurship, other than the most casual, tends to be quite intense in its time demands.

CBS News reports that roughly one in three young shoppers in the U.S. has admitted to giving themselves five-finger discounts at self-checkout counters, according to a recent survey. A response at X:

America does not have the moral cultural norms for there not to be a massive amount of theft. We’re too self-centered, individualistic, and we celebrate envy as a desert claim in the name of “equity.”

There is certainly a big cultural problem here, but I question the idea that Individualism and Community are opposites…traditionally, there has been quite a lot of both in America, as I believe Tocqueville observed. My thought is that both individualism and community are in danger of being replaced, and in many case have been replaced, by anomie.

Claire Lehmann suggests some books for helping children learn about history and philosophy. Other suggestions in the replies.

NYT finally reports what many others have been writing and speaking about for some time: the school closures for Covid are correlated with a sharp decrease in student learning. How do we square this data, though, with what we know about the preexisting generally poor low and declining quality of US public education?

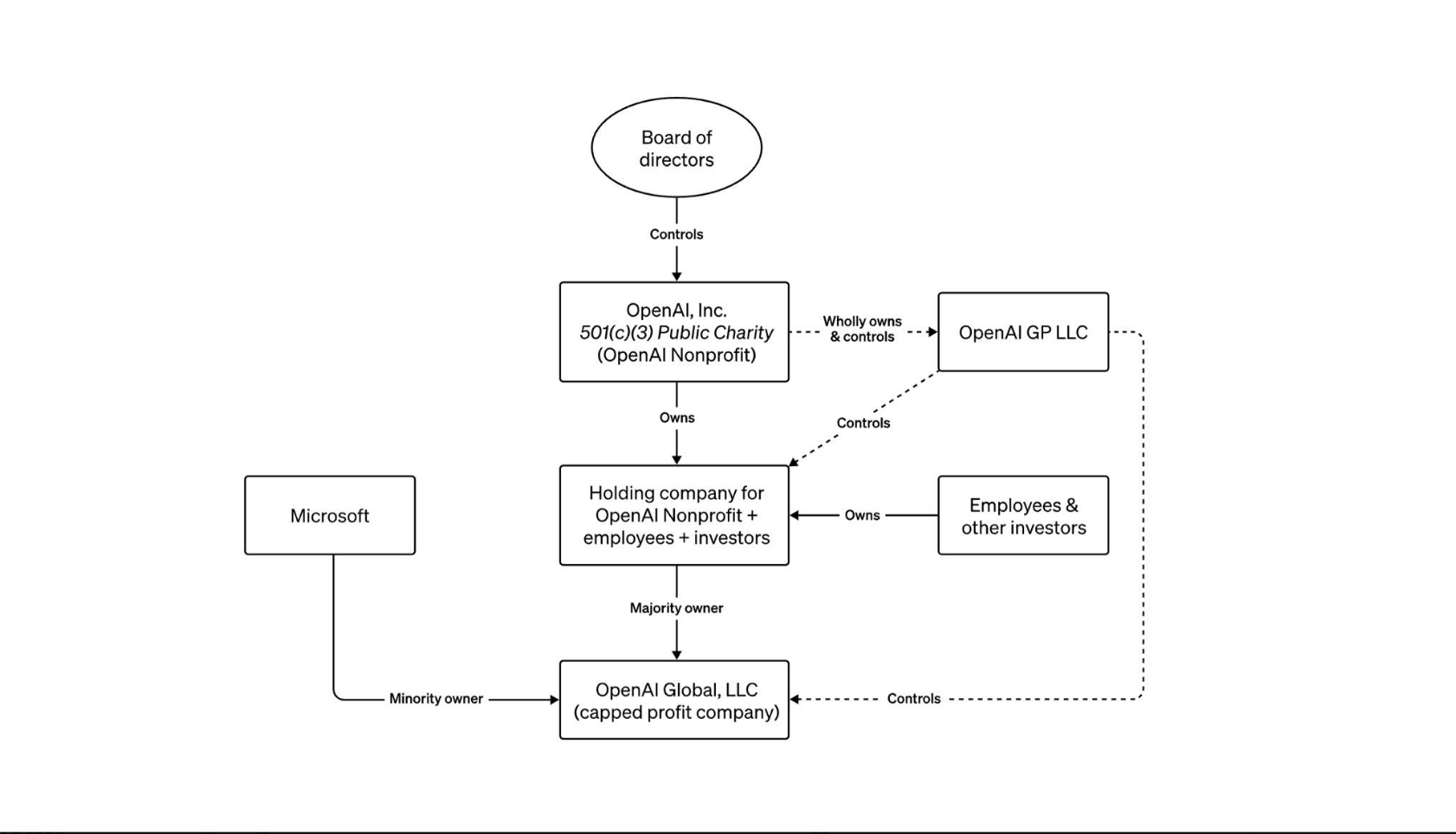

The AI world is all astir with the news that San Altman has been removed as CEO of OpenAI…and now, the board is negotiating with him for his possible return! There are many explanations floating around as to what is really going on. The organization/governance chart for this enterprise, which someone posted at X, is rather…unique.

Speaking of AI, somebody at X thought that Biden should have issued an executive order to require the rehiring of Sam Altman and his associate who also left. (Tweet now deleted.) There was no mention of what possible legal authority Biden might have for issuing such an order, but increasingly people seem not to worry much about such things. The other thing that struck me was that such an order would be analogous to an order by President Eisenhower to require the Traitorous Eight to return to Shockley Semiconductor in 1957. Or, even earlier, to require Bardeen and Brattain to remain at Bell Labs and keep working with Shockley on grounds that the transistor was such a critically important technology for national security and economic well-being.

A lot of people have trouble grasping the idea that if something important is being done by a particular institution, that doesn’t mean it could not be done equally well…or much better…by other institutions, including ones that may not yet exist. We see this phenomenon, for instance, in discussions of education and the future of the Social Security system.