One of the most frustrating things in researching General Douglas MacArthur’s World War 2 fighting style is dealing with the mayfly like life of the many logistical and intelligence organizations his military theater created. Without their narrative stories, you just cannot trust much of what has been written about the man’s fighting and command style. Nowhere is that clearer than with the radar countermeasures (RCM) and electronic intelligence (ELINT) Section 22, General Headquarters, South West Pacific Area (Sec 22, GHQ, SWPA). Born in November 1944 to support the air campaign against the Japanese bastion of Rabaul and dissolved in mid-August 1945 after the Japanese surrender. Section 22 gets but two ‘unsourced’ sentences in US Army lineage series history CMH Pub 60-13 Military Intelligence published in 1998 and not even a single mention CMH Pub 70-43, U.S. ARMY SIGNALS INTELLIGENCE IN WORLD WAR II, A DOCUMENTARY HISTORY, Edited by James L. Gilbert and John P. Finnegan, published in 1993.

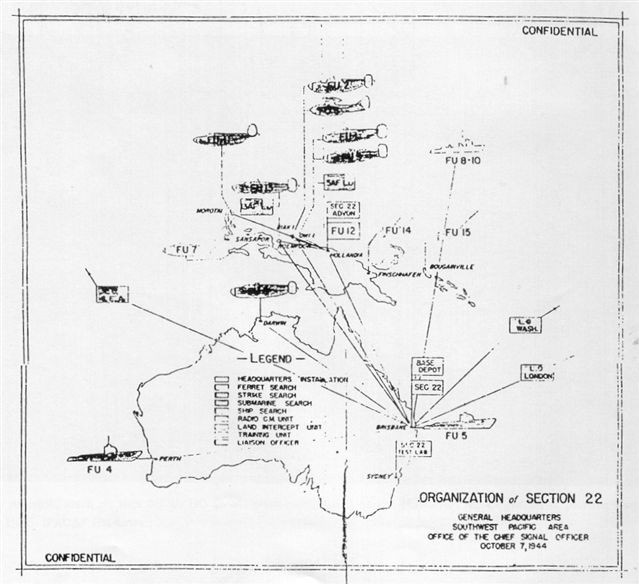

Yet Section 22 was a large, continent spanning, intelligence organization with squadrons of radar/electronic intelligence gathering planes, ships, submarines and multiple teams of “Retro-High Tech Commandos” doing their own tropical 1944-45 raids on Japanese Radar sites equivalent to the British “Operation Biting” or “Bruneval Raid” did 27–28 February 1942 to gather technical data on the German Wurzburg radar. See the poor copy of a microfilm document Section 22 organizational chart from Alwyn Lloyd’s rather eclectic book ‘Liberator: America’s Global Bomber’ (1993) below.

The job of peeling back the who, what, where, when, why, and how history of Section 22 — and why that history was buried for decades — is the work of many books and articles visiting archives across three continents. This column can at best occasionally take you on journeys describing Section 22 like that proverbial “blind man describing an elephant”.

This column has twice dealt with General Douglas MacArthur’s will-o-the-wisp Section 22 radar hunters. First with field units 12 and 14, “High tech Radar commandos” and later with the radar hunting USS Batfish — the US Navy’s champion submarine killer of WW2. Today’s column will pull back its focus from individual Field Units and show Section 22 over all at the peak of it’s size, capability and influence.

Section 22 in Oct 1944 had seven aircraft “ferrets” (named that for “ferreting out” radar signals), three surface ship ferrets, two submarine ferrets, along with two radar ground intercept teams, a mobile training team, a Section 22 Special Laboratory at Sydney and five liaison offices in the 5th Air Force, 13th Air Force, London, Washington D.C. and the China-Burma-India theater. Curiously, there were no similar liaison officers with 7th Fleet or to Admiral Nimitz’s command in Hawaii.

Section 22 was what post-war historians would call an impossibility in the WW2 Pacific, let alone MacArthur’s SWPA theater. It was both a “Joint and Combined” organization, that is joint service and combined nationality. It had US Army, Navy and Marines, British Royal Navy, Australian Army, Royal Australian Navy and Royal Australian Air Force as well as Royal New Zealand Air Force and Royal New Zealand Navy personnel.

To the best of my ability to determine, Section 22 Field Units on Oct 7, 1944 were as follows:

Field Unit 1 – Unknown/Unnumbered Aircraft Ferret*

Field Unit 2 – Unknown/Unnumbered Aircraft Ferret*

Field Unit 3 – Unknown/Unnumbered Aircraft Ferret*

Field Unit 4 – Submarine Ferret* associated Perth

Field Unit 5 – Submarine Ferret* associated Brisbane

Field Unit 6 – B-24 380th Bombardment Group (H), associated Darwin

Field Unit 7 – PV-1 Ventura (?) associated Sansapor*

Field Unit 8 – Surface Naval Unit* associated Brisbane

Field Unit 9 – Surface Naval Unit* associated Brisbane

Field Unit 10 – Surface Naval Unit* associated Brisbane

Field Unit 11 – Unknown/Unnumbered Aircraft Ferret*

Field Unit 12 – Australian Military Force (AMF) long range, RCM listening recon patrol/direct action Commandos (See: Kevin Davies, “Field Unit 12 Takes New Technology to War in the Southwest Pacific,” Studies in Intelligence Vol 58, No. 3 (September 2014) pages 10 – 20) — associated Hollandia

Field Unit 13 – This was a group of New Zealand radar physicists with 5th Heavy Bombardment Group, 868th Bombardment Squadron (H). This Squadron had the 10 cm SCR-717 anti-ship radar version of the B-24, the “SB-24 Snoopers.” They built their own B-24J Ferret hunter-killer, helped build a B-25J Ferret hunter-killer, and developed a special “Foxhole Ferret” radar intercept kit for minimally attended ground operations.

Field Unit 14 – AMF long range, RCM listening recon patrol/direct action Commandos (Again Kevin Davies) — Associated Finschnahfen.

Field Unit 15 – B-24 SQUADRON RAAF – FENTON, This squadron took over the Netherlands East Indies work that the 380th BG had been doing prior to their move to the Philippines. Apparently this F.U. was in training Oct 7, 1944. Associated Brisbane

FILLING IN THE BLANKS

The unnumbered Ferret aircraft associated with the above list of Field Units are as follows:

5th Air Force Bomber Command – Ferret VII B-24D — FB-24D1 THE DUCHESS OF PADUCAH. Ferret VII was on loan from Vth Bomber Command; it passed to 43 Heavy Bombardment Group (H) 63 Heavy Bombardment Squadron. Like the 868th, the 63rd Sqd had SB-24 Snoopers. Afterwards THE DUCHESS OF PADUCAH was used by 380 BG(H) 530 BS. It may also have been on temporary duty (TDY) 90 BG(H). It was salvaged was “war weary” May 21, 1945.

5th Air Force Bomber Command – Ferret VIII B-24D — FB-24D1 ATOM SMASHER was with 380 BG(H) 530 BS. It was later transferred to 43 BG(H) 63BS. Ferret VIII was originally to be assigned to 4th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron 13th Air thought to be on TDY 5AF; It suffered a major operational accident Dec 29 1944 and was scrapped.

5th Air Force Bomber Command — Captain Victor Tatelman’s B-25D Ferret “Dirty Dora II” with the 499th Bombardment “Bat outta Hell” Squadron, 345th BG (M) Air Apache’s. This plane started as a salvaged B-25D in named “Sir Beetle” at the Biak air depot. It was equipped with experimental Bell Lab’s radar hunting equipment and flew 36 radar hunting missions between the fall of 1944 and March 1945. The experimental equipment was removed at that point for a lack of Japanese radar targets in the Philippines.

13th Air Force — B-24J Ferret Hunter Killer, FU 13. It was built with resources in-theater to fill the Ferret role of the diverted FB-24D1 ATOM SMASHER.

13th Air Force — B-25J Ferret Hunter Killer, FU 13? It was built with equipment on-hand to duplicate the Bell Labs equipped “Dirty Dora II.”

7th Fleet — U. S. Navy PBY-5 Ferret flight, Lt Lawrence R Heron commanding, associated at various times with VPB-33, VPB-34, VPB-71 disbanded in May 1945. The flight wore out two PBY-5 aircraft before its disbandment.

UNNUMBERED SHIP FERRETS

7th Fleet — DD-445 USS Fletcher – [See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Fletcher_(DD-445)] 1944 & 1945 combat history) Ship joined 7th fleet April 1944 and is shown in ‘The History of US Electronic Warfare, Vol 1 by Alfred Price with a 1944 ELINT/Jamming unit picture between pages 264 & 265

7th Fleet — Motor Torpedo Boat (MBT) Squadrons. It is unclear if these were operations with F.U. 12 & 14 Kevin Davies wrote upon or were separate Section 22 F.U. The US Navy War Diaries and Muster roles on the Fold3 US National Archives document digitization service give evidence for both possibilities.

7th Fleet — USS Batfish, possible then FU #4 Submarine ferret — see my “History Weekend — MacArthur’s Section 22 Submersible Radar Hunters”, Posted Chicagoboyz.net by Trent Telenko on 1st March 2015

“The USS Batfish was based at Freemantle Australia for its war patrol #5 (October 8 – December 1, 1944) and the Batfish lost its primary APR-1 Elint operator on War Patrol #4 (July 31 – September 12, 1944), on 25 August 1944 due to nerves, and both WP #5 and #6 had much better RCM reports.”

SOME FRUSTRATION RESOLVED

So now you see why much of what has been said and written about General MacArthur cannot be trusted, if an intelligence organization that big can be erased from the US Military’s institutional historic record, and why I’ve had more than a little frustration on researching MacArthur’s will-o-the-wisp Section 22.

Notes and Sources —

Kevin Davies, “Field Unit 12 Takes New Technology to War in the Southwest Pacific,” Studies in Intelligence Vol 58, No. 3 (September 2014) pages 10 – 20

Peter Dunn, SECTION 22 GENERAL HEADQUARTERS, SWPA

AN INTELLIGENCE ORGANISATION DURING WWII – Australia @ War

http://www.ozatwar.com/sigint/section22.htm

Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR) World War 2 Narrative No.3, Radar, Copy No.3 -Archives New Zealand Reference AAOQ W3424 16

Captain Don C. East, USN, “A History of US Navy Fleet Air Reconnaissance, Part 1, The Pacific and VQ-1”

Alfred Price’s “The History of US Electronic Warfare. Volume 1: The Years of Innovation – Beginnings to 1946”. (Westford, MA: Association of Old Crows, 1984)

“The Search For Jap Radar”, RADAR No. 10, 30 June 1945, published by MIT Radiation Laboratory through USAAF Air Communication Officer Major General Harold McClelland, page 9.

Vic Tatelman’s Biography

http://www.eaf51.org/newweb/Documenti/Storia/B25%20Pacific_ENG.pdf

Capt. Vic Tatelman’s Photos

http://www.adamsplanes.com/Vic%20Tatelman’s%20photos.htm

Vic Tatelman’s Stories

http://www.adamsplanes.com/Vic%20Tatelman’s%20stories.htm

Trent Telenko, “History Weekend — MacArthur’s Section 22 Submersible Radar Hunters”, March 1, 2015.

https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/47665.html

Trent Telenko, “History Friday — MacArthur’s High Tech Radar Commandos” January 2015.

https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/47125.html

“The Special Flight”

Liberator Operations on Radar Countermeasure With 160 Squadron, 159 Squadron and 1431 Flight

SEAC January, 1944 to October, 1945

A special thanks to Peter Dunn and Robert Livingston for their assistance in researching this article.

Another great article. It is sad how much I think I “know” that probably isn’t true, and I’ve studied WW2 for many years. Thanks again for looking at these primary sources and doing the research yourself in an unbiased and thorough manner. You are a major credit to this blog.

I just read Conrad Black’s “Flight of the Eagle” which is a US history. His books are always well written and give a new perspective on some things. He is a big fan of MacArthur and argues he was correct in his ideas about Korea, including bombing Manchuria. He has some other ideas about Vietnam but here, I am less impressed. Still, an interesting POV.

Mike K,

MacArthur’s SWPA command style was of “Service Coordination & Cooperation” with MacArthur as the final arbiter of operations and strategy level decisions and the flag level principles of the various services being scattered over thousands of miles of territory during the planning and decision making for future operations.

MacArthur occasionally “held court” with his senior commanders and made the various commanders fight it out in front of his staff to figure out who was trying to snow him. This was a profoundly low-trust, political style that required the “Prince” that was “Holding court” be very much on the top of his game to make good choices.

MacArthur had both the intellectual and experiential chops to pull that off. This, BTW, was Pres. Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s command/leadership style, and MacArthur made clear that in terms of DC politics he was a babe-in-the-woods compared to FDR.

By way of contrast, the Central Pacific command style was a centralized, Navy dominated, “joint” style with the US Navy as “first among equals” with all the senior flag principles being in one place under Adm. Nimitz’ eye to make all the strategic and many of the operational decisions.

MacArthur, by providing signals intelligence directly from the Allied Central Bureau, and now it seems Section 22 Radar intelligence, to all major commands operating in his theater exerted command influence over them, even if they reported directly to Nimitz. I am speaking here of the signals intelligence liaisons MacArthur had with 3rd/5th fleet with Admirals Halsey and Spruance.

MacArthur’s Central bureau and Section 22 were much more horizontal and decentralized intelligence institutions than the US Navy’s and US Army Signals intelligence mandarins were willing to continence. For example, the creation and updating of the Japanese Radar electronic order of battle had to be mainly decentralized to be of any use to the airmen and sailors fighting the war. However, these more horizontal intelligence organizations suited MacArthur’s command style to a Tee.

The US Navy and particularly Admiral King never realized how MacArthur’s more rapidly reacting intelligence services manipulated the Pacific Fleet into supporting MacArthur’s drive to the Philippines over Formosa.

The whole Philippines vs Formosa argument is interesting and I have never decided who was right. Black’s comments are more in the way of an affection for Mac than any real policy analysis. The atomic bomb probably kept us from seeing who was really right. And a good thing, too.

Mike K,

Mac was right and King/Nimitz were wrong. And it isn’t even close.

The following are the 13 Feb 1945 Effective combat strengths of US Army Division in Luzon.

37th Div 95%

40th Div. 88%

1st Cav Div 85%

32nd Div. 81%

43rd Div. 71%

158th RCT 66%

These strength shortages were due to the absolute priority for infantry replacements for the Hurtgen Forest (The First Army had suffered 24,000 dead, wounded, captured or missing in action, plus another 9,000 disabled by other nonbattle injuries in the 5-month fight there.) and Battle of the Bulge depleted US Army in Europe.

The SWPA got only 5,000 infantry replacements for the whole of the 6-month (Jan – June 1945) Luzon campaign.

This compares to the 12,000 US Army infantry replacements 10th Army got for 83-day Okinawa campaign.

American Army rifle companies TO&E strength was 193 men. It had three 40 man rifle platoons with three 12-man rifle squads with 10 M-1 Garand rifles and a Browning automatic rifle. Plus two MG squads with two .30 cal air cooled medium machine guns and a 60mm mortar squad.

An American dismounted Cavalry Troop (Company) was 167 Troopers with three rifle platoons of 29 Troopers. The Cav Platoons were composed of a 5 man HQ and three eight trooper squads. Each squad had a Squad Leader with an SMG, a BAR man, an assistant BAR man (armed with an M1903 rifle with M1 grenade launcher) and five troopers armed with M1 rifles.

Given the higher casualty rate of infantry rifle companies, the above division effective combat strength meant the divisions [and 158th regimental combat team (RCT)] had rifle companies (or Cav Troops) at 80, 60, 40 and even 30 men.

This shortage of US Army rifleman was made up by over 30,000 armed Filipino guerillas that rose up when the American Army liberated the Philippines.

Now imagine an invasion of Formosa without those 30,000 Filipino guerillas on the American side with likely triple that number of Japanese supporting civilians on the Japanese Army’s side.

” Battle of the Bulge depleted US Army in Europe.”

I think it is Forrest Pogue’s biography of Marshall that goes into the severe problems he had with Congress and the Selective Service boards that shut down the draft in 1944. They did not want to see any more draftees and the army was desperate for men after the Bulge. Eisenhower went through the cooks and JCH Lee’s army of logistics people to get more infantrymen. Lee had an enormous empire and he was referred to as “Jesus Christ Himself Lee.”

Your point about the Philippine guerrillas is a good one. I don’t know if you have read any of WEB Griffin’s novels about WWII but he goes into great detail about Wendell Fertig.

During his post-war years he was widely regarded as a hero by the people of Mindanao, and was a highly respected figure among the U.S. Special Forces.[6][7] One authority lists him among the top ten guerrilla leaders in history.[1]

My comment has not appeared and I”m getting a duplicate comment error message.

” Battle of the Bulge depleted US Army in Europe.”

I think it is Forrest Pogue’s biography of Marshall that goes into the severe problems he had with Congress and the Selective Service boards that shut down the draft in 1944. They did not want to see any more draftees and the army was desperate for men after the Bulge. Eisenhower went through the cooks and JCH Lee’s army of logistics people to get more infantrymen. Lee had an enormous empire and he was referred to as “Jesus Christ Himself Lee.”

Your point about the Philippine guerrillas is a good one. I don’t know if you have read any of WEB Griffin’s novels about WWII but he goes into great detail about Wendell Fertig.

During his post-war years he was widely regarded as a hero by the people of Mindanao, and was a highly respected figure among the U.S. Special Forces.[6][7] One authority lists him among the top ten guerrilla leaders in history.[1]

This was the comment that vanished.

There…fixed.

Mike K,

FYI, there was something funky about the “Wendell Fertig” link, which seems to be why both posts went to moderation.

I’ve read almost all of Griffin’s books that are written before 2005. They have deteriorated since as he is quite elderly now. Some, especially the Argentina series and the WWII series, have a lot of information that he got from non-traditional sources, like his neighbors in south Alabama.

The US Navy and particularly Admiral King never realized how MacArthur’s more rapidly reacting intelligence services manipulated the Pacific Fleet into supporting MacArthur’s drive to the Philippines over Formosa.

All the history I have read about that debate MacArthur and Nimitz had with Roosevelt watching in Hawaii over Philippines vs. Formosa in 1945 never mentioned this. All of them made it out that MacArthur won it by declaring that not liberating the Christians in the Philippines and the political firestorm from not doing that were what won Roosevelt over.

Thank You for your research on this Trent. It is amazing how the anti-MacArthur cabal was able to write the history of the Pacific war without any correction from MacArthur supporters.

Though I do still think MacArthur screwed up big time twice, first in thinking he could stop the Japanese with only two good trained regular divisions and not implement Plan Orange immediately upon hearing about Pearl Harbor and the second time in Korea when he ignored intelligence about Chinese intentions. If he had acted upon that intelligence, he could have set up a slaughter of Chinese troops that would have made Passchendaele look like a school picnic. He would probably have gotten permission to do a limited bombing on the other side of the Yalu River after that on humanitarian grounds on preventing another slaughter.

“I do still think MacArthur screwed up big time twice”

The worst, although not that significant in the long run, was his freezing on December 8, 1941 and allowing Japan to destroy the Air Corps in Luzon. Another, not his fault, was ordering the surrender of Sharp in Mindanao when Wainwright surrendered Corregidor.

The Korea story was one place where I disagreed with Black and where Mac seemed to be getting senile. Ridgeway saved that situation although we lost a lot of casualties before the truce. Black says Eisenhower told the Chinese he would use nukes if they didn’t sign the armistice. The wiser course for Mac would have been to stop at Pyongyang where the peninsula is narrow. Going to the Yalu was a mistake. I was in 8th grade and had a map of Korea on my bedroom wall.

Joe,

Nothing was decided at that conference. Roosevelt made no real commitment to the Philippines over Formosa. Events later dictated the choice.

There was a lot going on inside the US Navy regards the intelligence mandarins fighting to control naval intelligence distribution that allowed MacArthur to undercut both them and Adm. King.

Section 22 mapped out the Japanese radar networks of the West Pacific and Southern/Central Philippines for Halsey’s raid on the Palau’s island group and Mindanao in the Southern Philippines in late 1944. This intelligence was provided by US Army signal corps liaison with 5th fleet — along with whatever ULTRA decode MacArthur had of the area and that the USN intelligence mandarins hadn’t distributed to the fleet yet — directly to Adm. Halsey.

Halsey used that data for the raid and called out that the Japanese were exceedingly weak, that we should go straight to Leyte, and we should skip Peleliu (or Beliliou) in the Palau island group.

Halsey was wrong on the first and right on the second, but MacArthur jumped upon it and Nimitz agreed.

The bottom line was that logistics, in terms of things like infantry replacements, sea lift, and particularly the need to screen that sealift from Japanese land based airpower from Luzon was what really killed the Formosa plan, not MacArthur’s reported histrionics.

Nimitz used the logistical chops requested from the War Department for Formosa to do both Iwo Jima and Okinawa instead, with a great deal left over for either Nimitz’s China coast operation or Olympic.

As far as the Dec 8th 1941 debacle, from 0330 until 1014, HQ USAFFE specifically denied Brereton permission to launch his bomber force at Clark (19 B-17s) against Japanese port facilities on Formosa.

It also did not allow Lt. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton to speak directly with MacArthur either in person or on the telephone.

FEAF dispersed the B-17 bombers to holding positions in the air at about 0800 to avoid an attack expected that morning. Most of the bombers were in the air most of that morning.

MacArthur gave Brereton permission to attack Formosa during a telephone call at 1014, and Brereton recalled the dispersed force which began landing about 1100.

It took two to two and a half hours to refuel, load bombs, and prepare an attack, thus FEAF’s aircraft were on the ground at about 1220 when the Japanese air forces, delayed by fog on Formosa for roughly five hours, reached Clark.

Why neither Brereton nor MacArthur thought to disperse the B-17’s to airbases out of range south of Clark Air Field to try again the next morning has never been explained.

This fade south and launch the next morning technique was how B-17’s were used in New Guinea in 1942-43…but only after the bad experiences at Clark Air field and Darwin.

Now, some figures of merit for consideration in the MacArthur’s FEAF debacle.

First figure of merit:

To hit one 60 ft. x 100 ft. target in WWII required 1500 B-17 sorties carrying nine thousand 250 lb bombs because they had a circular error probability of 3300 feet. [1]

Circular error probability is defined as 50% within the CEP circle around the target and 50% landing somewhere else outside it.

That level of performance assumed,

1) Good daylight visibility and

2) Good target contrast from the background to achieve a good aim point.

A second figure of merit:

There were nineteen B-17’s available to the FEAF at Clark Air field with a maximum payload of 12 x 500 lb bombs for a total of 228 bombs in one 19 sortie mission.

Point in fact, the FEAF B-17’s only had 100 lb and 300 lb bombs to work with. [2] And this was 12-15 months before USAAF armorers got around to placing multiple lighter bombs on the B-17 500 lb. bomb stations.

A third figure of merit:

There was no effective way for FEAF B-17’s to deliver their loads of bombs through fog on Formosan airfields, to get in the first punch against Japanese airpower, even if MacArthur had said yes sooner.

It was years before the US Military deployed radio beam navigation for night/bad weather bombing (LORAN) and it was February 1944 before the H2X (AKA “Mickey set” or more properly the AN/APS-15) 3cm airborne radar arrived in USAAF service in UK based B-17’s to aim bombs through clouds and murk. [3] This also leaves out accuracy considerations of upper level jet stream wind patterns over Formosa.

A fourth figure of merit is the following partial list of Japanese military airfields on Formosa. [4]

Okayama Airfield

Shenei, Shoka

Tainan Airfield

Japanese airfield

(Home of 84 A6M2 Zero/Zeke fighters & 100 bombers used 8 Dec 1941 at

Clark Field)

Kaohsiung (Takao)

Harbor and airfield

Toko Airfield

Japanese airfield

Toshein Airfield

Japanese airfield

Toyohara Airfield

Japanese airfield, located in the central portion of the island

Koshun Airfield

Japanese emergency airfield

Matsuyama Airfield

Japanese airfield

Karenko Airfield

Japanese airfield

Shinchiku Airfield [5]

Japanese wartime airfield

Koryu Airfield

Japanese wartime airfield

Anyone who thinks nineteen pre-B-17E model Flying Fortresses in December 1941 could make a meaningful dent in the above Japanese

airfield infrastructure on Formosa, given that B-17 force’s technical limitations, and the efforts in terms of sorties that the 5th Air Force put into suppressing Formosan airpower in the anti-Kamikaze campaign of March thru June 1945, is trafficking in delusion. [6]

There was no way that the FEAF could survive in range of Japanese air power on Formosa in 1941, and it didn’t. Nothing MacArthur did, or didn’t do, would have changed that outcome.

The only thing that would be different, had MacArthur said “Yes” to a B-17 raid on Formosa hours sooner, was the place where those B-17’s died, in a raid over a Japanese port facility over Formosa or in the ocean between Formosa and the Philippines as Japanese Zero fighters followed them back to clark field.

More modern evaluations — AKA less colored by immediate post-war reputation protection and organizational agendas — of the FEAF performance are more telling.

The best look at that I have seen on that debacle is in Chapter 10 of “Why Air Forces Fail: The Anatomy of Defeat”, edited by Robin Higham, Stephen J. Harris, which evaluated the real readiness of the Far Eastern Air Force on Dec 8, 1941. That essay, titled “The United States in the Pacific” by Mark Parillo, addresses the FEAF Philippines performance starting at page 296.

The bottom line was that the B-17 force at Clark field did not have:

1) The intelligence to effectively strike Formosa air fields with the limited number of bombs available at Clark Field. There were No pre-war over flights of Formosa, No human intelligence and thus No intelligence photos for inexperience photo interpreters to work from, There were reasons for this. USAFFE persistently denied Brereton’s efforts to conduct reconnaissance of Formosa prior to 8 December. MacArthur didn’t want to start a war before he was ready, nor did he have directions from Washington DC to fly such missions.

The 19th Bomb Group’s target files apparently did contain enough information to strike a Formosan port facility, making the planned attack on Formosa more than just a shot in the dark. However, given that the invasion fleet had already sailed. It would have been a useless gesture.

2) The B-17 did not have the accuracy to strike ships at sea from 20,000 feet, See B-17 performance per pre-war doctrine at Midway, but unknown at the time,

3) Nor did the B-17 force have the logistical chops in its supporting FEAF fighter units — which lacked coolent for high altitude operations and were so short of .50 cal ammunition for its P-40E’s there was no test firing of guns until combat commenced — to conduct escorted strikes at the B-17’s normal operating altitudes anywhere within P-40 range,

5) The B-17 force at Clark Air field were pre B-17E models lacking tail guns and powered turret guns. Thus they were dead meat for Japanese A6M Zero/Zeke fighters with 20mm cannon on Formosa (See

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/B-17_Flying_Fortress_variants),

6) There was no effective early warning system at Clark Field, as then Captain Chennault’s exercise tested as effective telephone. radio & binocular equipped ground observer system was drummed out of the Army Air Service (along with his person) as a threat to the Heavy Bombardment clique’s B-17 budget. And like Pearl Harbor, FEAF SCR-270 Radar units and fighter controllers were too inexperienced to be of any use.

The B-17 force was sold as a high value “force in being” to the American high command such that it made the force’s commitment without a clear high value target — like the expected Japanese invasion convoy — a non-starter, given a lack of clear targets on Formosa.

The pattern of Axis versus Allied airpower in WW2 was that the two major Axis powers had made the transition to 1st Generation piston engine mono-plane fighters & bombers, and it took a year of these more advanced aircraft being in service before they could be used to best advantage in terms of proper logistics. Then it took further months of combat to get proper tactical doctrine for this new equipment.

German had the Czech crisis, Spain and Poland to iron these things out before the main event in the Battle of France.

Japan had the Sino-China War starting in 1937, plus major border incidents with Russia, before dropping down on the FEAF at Clark Field.

Clark field was too close to a modern, combat tested Japanese Air Force to survive and nothing Gen MacArthur did, or did not, do would have changed that outcome.

Notes:

1) “Effects-Based Operations” Col Gary Crowder, Chief, Strategy,

Concepts and Doctrine Air Combat Command. See Document Link:

http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/dod/ebo_slides/030318-D-9085-024.pdf

2) See the “MacArthur’s Pearl Harbor” section at

http://www.homeofheroes.com/wings/part2/00_infamy.html

3) See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LORAN and

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H2X_radar

4) See: http://www.pacificwrecks.com/provinces/formosa.html

5) The following link shows B-25 Mitchells using 5th Air Force low

level airdrome attack techniques on the Shinchiku Airfield complex in

April 1945 — http://shulinkou.tripod.com/dawg2e.html

6) See the 5th Air Force’s 1945 Formosa campaign history at

http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/AAF/V/AAF-V-16.html

Good point about the 1941 air power disparity between Formosa and the Philippines, Trent.

Note also that the White House and War Department both treated B-17’s as their version of the Sioux “Ghost Dance”

Joe Wooten,

The interesting thing about MacArthur’s biggest mistakes is that he was usually in a cloud of flag rank and political conventional thinking when he did them.

Nobody but nobody in the American government thought that the Chinese were going to intervene in Korea.

Point in fact we were planning phased withdrawals of forces as we were moving to the Yalu.

See:

Refighting the Last War: Electronic Warfare and U.S. Air Force B-29 Operations in the Korean War, 1950-53

Author(s): Daniel T. Kuehl

Source: The Journal of Military History, Vol. 56, No. 1 (Jan., 1992), pp. 87-112

Published by: Society for Military History

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1985712

…The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) approved sending two additional B-29 units to FEAF, and on 8 July 1950 FEAF Bomber Command was formed. Although these units had no atomic capability, they could conduct conventional bombing operations, and within a week they were engaged in combat. By the end of July the first two units which SAC had sent to the Korean theatre, the 22d and 92d Bomb Groups, were augmented by two additional units, the 98th and 307th Bomb Groups. As the United Nations (U.N.) forces retreated into the Pusan Perimeter, FEAF/BC operated in support of a three-fold mission: close air support of hard-pressed U.N. ground forces, interdiction of North Korean lines of communication, and destruction of North Korean war-related industry.’

The B-29s systematically wrecked nearly every significant industrial installation in North Korea within a matter of weeks, and by late 1950 the bombers were almost out of targets, due to the U.N. advance into North Korea and the JCS-imposed prohibition on operations across the Yalu River. The 22d and 92d Bomb Groups were even returned to the United States in October, as the Air Force looked towards an end to hostilities.2

1. John Pimlott, B-29 Superfortress (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1953), 52;

James F. Schnabel and Robert W. Watson, The History of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Volume III, The JCS and National Policy, The Korean War, Part I (Washington: JCS Joint Secretariat, Historical Division, 1978), 179;

Robert F. Futrell, The United States Air Force in Korea, 1950-53 (Washington: GPO, 1983), 45-46, 87, 179;

Far East Air Forces Bomber Command (FEAF/BC), “Heavyweights Over Korea,” Air University Quarterly Review 8 (Summer 1954): 99-100;

Curtis E. LeMay, with MacKinley Kantor, Mission with LeMay (New York: Doubleday, 1965), 485.

2. Futrell, USAF in Korea, 1950-53, 185.

And as for bombing North of the Yalu to kill Chinese, see the “political correctness” of the Truman Administration below, before there was a description of the malady:

Raiding the Beggar’s Pantry: The Search for Airpower Strategy in the Korean War

Author(s): Conrad C. Crane

Source: The Journal of Military History, Vol. 63, No. 4 (Oct., 1999), pp. 885-920

Published by: Society for Military History

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/120555

“…Rather than bomb a single target system as in the assault on German oil in World War II, these objectives were chosen because of their concentration of different industries, similar to the selection system used in the bombing campaign against the Japanese. O’Donnell had commanded a wing under LeMay in those operations, and though SAC planners preferred destroying the targets with demolition bombs, O’Donnell and LeMay wanted to repeat the urban area firebombing they had executed against Japan.5

This became apparent as soon as O’Donnell arrived in Tokyo. When he was introduced to MacArthur, the airman quickly proposed “to do a fire job on the five industrial centers of northern Korea.” When MacArthur asked for more details, O’Donnell said that they had learned in World War II that bombing tanks, bridges, and airdromes was useless. Instead of such “infighting,” MacArthur should announce to the world that communist reactions to his pleas for peace forced him to use

“against his wishes, the means which brought Japan to its knees.” His declaration of intent to burn the industrial cities of North Korea would also serve as a warning to get all noncombatants out, and systematic attacks would begin after twenty-four or forty-eight hours. MacArthur listened to the whole presentation and replied, “No, Rosy, I’m not prepared to go that far yet. My instructions are very explicit.” He did agree to bomb military objectives in those cities with high explosives, and added, “If you miss your target and kill people or destroy other parts of the city, I accept that as part of war.” MacArthur’s sentiments ab4out indiscriminate firebombing would be echoed by later Joint Chiefs of Staff targeting directives. LeMay complained to interviewers in 1972 that his plan might have convinced the communists that the United States was serious and ended the war. Instead the war went on and “every town in North Korea and every town in South Korea” was destroyed anyway. He believed that “once you make a decision to use military force to solve your problem, then you ought to use it and use an overwhelming military force…. And you save resources, you save lives-not only your own but the enemy’s, too.”6

5. Vandenberg to Stratemeyer, 3 July 1950, Redline Message, TS 1814, Lemay Diary #2;

Maj. Ilarold D. Jefferson, “Development of FEAF Bomber Command Target System,” FEAF Bomber Command History, 4 Jul-31 Oct 1950, vol. 1, book 1, File K713.01-1, AFfIRA.

6. O’Donnell to LeMay, 11 July 1950, File FEAF 1, Box 65, LeMay Papers; Coffey,

Iron Eagle, 306.

I did say that there was no long term consequence of the Clark Field fiasco. Frank Kurtz in his book “Queens Die Proudly” written by White, recounts the confusion that morning as the crews waited for the word to do something. Dispersal was a better option than a futile mission.

The Air Corps was not alone. The Navy had non-functional torpedoes until 1943.

Mike K,

The “Charlie Foxtrot’s” of the American military intelligence at the beginning of WW2 were repeated in exquisite detail during Korea to the same General, MacArthur, for many of the same reasons.

It wasn’t until the American National Security public policy “unicorn” known as the Goldwater-Nichols Act that some of those issues got addressed.

See:

1. Two Strategic Intelligence Mistakes in Korea, 1950

Perceptions and Reality

P. K. Rose

https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csi-studies/studies/fall_winter_2001/article06.html

2.Days of Future Past

Joint Intelligence in World War II

By JAMES D. MARCHIO

Joint Force Quarterly May 1996

http://www.higginsctc.org/intelligence/WW2Intel.pdf

3. The Evolution and Relevance of Joint Intelligence Centers

Support to Military Operations

James D. Marchio

https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csi-studies/studies/vol49no1/html_files/the_evolution_6.html#_ftn33

and

4. The Collapse of Intelligence Support for Air Power, 1944-52

Two Steps Backward

Michael Warner

https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csi-studies/studies/vol49no3/html_files/Intel_Air_Power_4.htm

This passage from “Collapse” is particularly cringe worthy.

Consequences in Korea

The Truman administration’s decision to allow the “departments” to provide their own intelligence thus abetted, in practice, a situation in which a single service, through simple inattention, could deprive the nation of a valuable asset. In Korea, a surprised US Air Force had to reconstruct, almost from scratch, the sort of intelligence support for strategic air operations it had enjoyed in 1945. For the first two months of the conflict, a single reconnaissance technical squadron in Yokota, Japan, had to handle all photo interpretation work for the US Army and Air Force in Korea.[29] The Army had pledged in a series of deals dating from 1946 to handle much of the interpretation of photos of the front-lines, but the Eighth Army had no photo-interpreters at all until February 1951, by which time United Nations forces had twice been threatened with eviction from the Korean peninsula. When Lt. Gen. Matthew Ridgeway took over the Eighth Army in late December 1950, he found that his command literally did not know the sizes and locations of the Chinese formations facing it. To add insult to injury, an urgent reconnaissance campaign to locate those forces found little or nothing, largely because the harried photo-interpreters were relying in most cases on imagery alone to spot camouflaged Chinese positions, without the aid of other intelligence sources.[30]

Something seemed to have gone seriously wrong. Indeed, the chief of the Far East Air Force, Lt. Gen. Otto Weyland, complained that “it appears that these lessons [of World War II] either were forgotten or never were documented.”[31] Not until mid-1952—two years into the conflict—did theater command have at its call an all-source imagery intelligence, targeting, and battle-damage assessment capability.[32] By the end of the war, imagery support was once again competent and robust, but recouping that capability had been expensive in time, money, and lives—and there was still little understanding that the job was perhaps too big for any one service.

James Marchio’s research adds an interesting side note. Early in the Korean war, the several commanders-in-chief of the unified and specified commands endorsed a director of naval intelligence proposal to fashion joint intelligence centers in each of their commands—an idea that was soon forwarded to the Joint Chiefs of Staff. For some still undetermined reason, the Joint Secretariat in 1951 returned the proposal with the cryptic explanation that it had been “withdrawn from consideration by the JCS.”[33] That is roughly where matters would stand until the implementation of the Goldwater-Nichols Act, almost four decades later.

These are the source notes for that passage above.

[29]Futrell, The United States Air Force in Korea, 1950–1953, 545–46.

[30]Ibid., 272–73.

[31]Cited by Robert F. Futrell in “A Case Study: USAF Intelligence in the Korean War,” in Walter T. Hitchcock, ed., The Intelligence Revolution: A Historical Perspective [Proceedings of the Thirteenth Military History Symposium], (Washington: Office of Air Force History, 1991), 275.

[32]Futrell, The United States Air Force in Korea, 1950–1953, 501–4.

[33]James D. Marchio, “Support to Military Operations: The Evolution and Relevance of Joint Intelligence Centers,” 41–54.

Trent, thanks for the clarification. I guess what I had read over the years about certain intelligence guys warning the Chinese were serious about coming across the Yalu and being ignored by MacArthur were wrong. I did know that Truman’s administration was not concerned before it happened.

Joe Wooten,

There were a few low level CIA and US Army analysts saying the Chinese were going to come. They were buried in a sea of politically correct group think. Group think that MacArthur himself agreed with.

After the disaster, Mac was made the goat for the group think.

Mac was a big boy who played the game and lost. That is usually what happens to high end politicians at the end of their careers.

The thing about learning all of this is that it makes Pres. Truman’s reputation look much smaller in much the same way history has made General Omar Bradley’s reputation much smaller.

Hmm, here’s a data sheet for The Duchess of Paducah.

http://380th.org/HISTORY/PARTV/DuchessPaducah.htm

Though the data’s a bit sparse, the site’s interesting because there’s a link to the Duchess’ mission history and photos of the airplane, as well as a lot of the other bombers associated with the 380th Bomb Group.

“There were a few low level CIA and US Army analysts saying the Chinese were going to come”

One of the reasons why I have read all of WEB Griffin’s original novels, those from 10 years ago and earlier, is that he tells many of these stories with a mixture of real and fictional characters. One of them has the story of the guy who figured out the details of the Inchon invasion. There were small islands in the channel that had to be taken without giving away the invasion plan.

His Marine Cops series has a lot about the Australian who ran the Coast Watchers in WWII. I have a copy of that guy’s memoirs.

He also has the story of how the Raiders were formed. I had a high school teacher who had been a Raider.

Marine Cops?

I thought Navy SP’s did the job?

It’s a novel and I don’t know the facts but he does credit a navy guy with the plan. Many of the people who took the islands were Korea police. The navy guy was David Taylor and he is featured in the story.