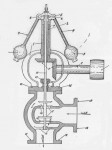

The object shown is a governor for an engine. This device was invented by James Watt for use with his steam engine, and has been applied, in one form or another, ever since. It allowed the engine’s use in applications where precise speed control was essential, notably textile manufacturing, and was an invention of great economic and conceptual importance.

It strikes me that the role played by the legal profession and the financial industry is analogous to the role of an engine governor. Like the governor, law and finance are control systems; they are essential enablers and regulators of the activities of the rest of the economy. But also like the governor, the percentage of total system resources that they themselves consume should be reasonably small.

What would we think of a governor that scarfed up 30% of the horsepower of the engine that it was serving? Most likely, we would conclude that it was either poorly designed or inadequately maintained, or both.

There is no question that the legal and financial industries are both vital. Contracts must be drafted, disputes must be adjudicated, and capital must be allocated effectively. But the numbers of people in these industries, and the share of national income devoted to their compensation–along with related expenses such as buildings and computer systems–is perhaps excessive.

For discussion:

1)Would you agree that the legal and finance industries presently represent a more-than-optimal share of the overall economy?

2)If so, what factors have led to this situation? In particular, to what extent is it a function of market failure versus a result of unwise government policy?

3)What, if anything, should be done to correct the situation?

As an engineer I’ve spent a good amount of time dealing with feedback control systems. People like to try to represent the fed as some sort of negative feedback system. I don’t really agree. I see the fed as, ideally following along after the economy trying to match the money supply to GDP. And adding more money to create inflation, and, er, provide stimulus (ha ha.)In reality, the fed seems to be mainly psycodrama for whichever jerk is in charge.

This isn’t feedback, it’s a combination of after the fact response, and forcing. and it doesn’t work very well, either. To put it in Keynsian terms, would an economy “overheat” without government input?

The free market works more like a feedback mechanism without external interference. The invisible hand has its finger on the controls. I don’t think an economy could be modeled as one big feedback loop. More like lots of little, small loops inside one big system. Which is probably not really modelable with any real accuracy because too much is unknown, and it’s too complex. I have never seen a really good overall economic model, for this reason.

The reason a governor works so well is that it’s tightly tied to the variable it’s controlling, and the loop is a lot faster than the rate of change of the variable being controlled. Imagine a governor with a 6 month to year delay between cause and effect, and dozens of other factors with as much input and the output starts to look more like the economy. A system like that is likely to have huge, nearly random looking excursions, which is a lot like what we see.

Feedback is one of the most misused terms I’ve seen.

try this one:

http://electronicdesign.com/article/analog-and-mixed-signal/what-s-all-this-p-i-d-stuff-anyhow-6131.aspx

Dunno. I was talking to some students participating in the student inventor’s contest at the U, and as engineering students that shared the belief that all engineers have, that engineering constitutes the real creative act and that all the financial stuff was just expensive window dressing.

I countered that sentiment, expressing the view that our modern technological society had its origins in the Medici Bank, where it was the emergence of new modes of directing money that was the spark. Much as I share the engineering philosophy, which is perhaps a version of Marx’s Labor Theory of Value, you need someone to put the capital in Capitalism. Finance is not so much as a regulatory function as an enabling function.

Perhaps complaining about the resources going into Finance instead of paying the engineers and workers is perhaps like complaining about the resources going into the fuel required to run our machinery.

I don’t know as much about the financial industry, but it is increasingly looking like the legal industry is going to experience the same downsizing everyone else has — Instapundit and law professor Glenn Reynolds is warning about the legal bubble.

I’m not sure about financial institutions but lawyers are a plague on business of all types. Two of my kids are lawyers and both do useful things for society.

I have spent a lot of time with lawyers in the medical malpractice business. Most of the plaintiff lawyers I knew were sincere in wanting only “good” cases and were uninterested in frivolous cases. However, I have also seen two frivolous cases in which I was the defendant. One was a case in which the patient died post-op, That case went to trial and we were exonerated plus awarded court costs (which we never could collect). The plaintiff lawyer was the president of the trail lawyers association of Orange County. I could not understand how he thought he could win that case. He had an expert who lied and maybe misled him about the merits of the case. In another case, the plaintiff had not paid a bill and had forged the surgeon’s signature on the insurance check. That was dismissed when I informed the plaintiff lawyer that I would sue him for malicious prosecution.

My point is not that I have had malpractice suits filed against me. It is that there is a certain amount of friction created by the threat of lawsuits. It is an additional cost in the transaction. The new Consumer Protection Agency created this year by Congress will be a nightmare for businesses that manufacture consumer goods. The Democrats are, of course, allied with the trial lawyers and have little interest in business. Businessmen to them are always suspect and are motivated by profits which Democrats consider immoral.

The financial people seem to live in a world of their own. I watched the housing bubble with misgivings although I was also caught up in the imaginary “values” of houses. My house went up in value nearly fourfold over 20 years. It dropped 25% in the collapse but I still sold it for 250% of what I paid to buy it. I am still uneasy about the mortgage market and the finagling of home financing. I liked it better when I made a 20% down payment and the S&L serviced the loan. I’m sure that system limited profits but the exotic derivatives seemed to get out of control. I’m not sure the people using them understood what they were doing.

PaulM…totally agree about the importance of the financial industry. But no matter how important, there is an optimal size for everything.

See for example this link on the US financial industry as a % of the GDP.

The governors might govern better if they governed that which needed governance and which could be governed. That means abolishing the departments of Education and Energy, the endowments for the Humanities and Arts, public broadcasting, etc.

I think the financial industry worked much better when those who made bad decisions could go bankrupt. I just read an interesting book, The Lords of Finance, about the four heads of the great national banks in the 1920s. It supported my conviction that reparations had a lot to do with the 1929 collapse and the Depression. The world financial system was too fragile because that issue was always in the background. The author doesn’t like the gold standard much either. Keynes was right for so long that it is hard for many people to realize he is wrong now. There is nothing like politicians to screw up a good theory.

Or we might conclude that it was designed for the express purpose of harvesting energy from the engine, and that it was functioning more or less as intended.

Without getting into the unresolvable debate about the intentions of those who originally created the regulatory structure, I think it’s irrefutable that the current function and goal of those at the top of the structure is to maintain and enhance their own power and profit.

The irony of the situation is that if the financial and legal systems actually worked at their nominal “governor” functions, then hardly anybody except hard-line libertarians would notice or care. If the justice system actually provided some consistent and perceived measure of justice, if the financial system provided some measure of financial stability and prosperity, then people would just shrug at the high legal and compliance costs and get on with their business.

The two explanations that I can come up with for the current situation are:

1) The folks at the top really have no clue. They are honestly trying to make the system work and are failing.

2) The current turmoil is a sort of Hail Mary play for more power and control. Deliberately make the situation unbearable in the hopes that the solution will result in an even sweeter deal, and not a collapse of the system.

Confusing the situation is the fact that the legal and financial professions do face some degree of market test, so you can’t impute all of same the motives and world view held by politicians and other members of the true parasite class. The stupid/evil duality is much harder to understand for people who ought to be some of the smartest folks around.

Setbit, I think your two explanations are valid – in short, the “stupid” vs. “evil” question. Unfortunately for those of us NOT runing things, it’s even worse than that – it’s both options at once.

I think replacing the governor with a pilot-operated pressure reducing station and hiring Siemens to automate the management system would be ideal. But not that French version of Siemens (Areva?), they scare me. Combined with a high turndown, dual-fuel burner we should see some serious returns on our investment and a long life span with regular maintenance.

The financial crisis, I believe, came from a quest for more profits and the development of investment vehicles that no one understood. The financial firms were hiring physics PhDs and they were calculating risk with formulas that were pretty arcane. I think this article is the best explanation I’ve seen.

A year ago, it was hardly unthinkable that a math wizard like David X. Li might someday earn a Nobel Prize. After all, financial economists””even Wall Street quants””have received the Nobel in economics before, and Li’s work on measuring risk has had more impact, more quickly, than previous Nobel Prize-winning contributions to the field. Today, though, as dazed bankers, politicians, regulators, and investors survey the wreckage of the biggest financial meltdown since the Great Depression, Li is probably thankful he still has a job in finance at all. Not that his achievement should be dismissed. He took a notoriously tough nut””determining correlation, or how seemingly disparate events are related””and cracked it wide open with a simple and elegant mathematical formula, one that would become ubiquitous in finance worldwide.

For five years, Li’s formula, known as a Gaussian copula function, looked like an unambiguously positive breakthrough, a piece of financial technology that allowed hugely complex risks to be modeled with more ease and accuracy than ever before. With his brilliant spark of mathematical legerdemain, Li made it possible for traders to sell vast quantities of new securities, expanding financial markets to unimaginable levels.

His method was adopted by everybody from bond investors and Wall Street banks to ratings agencies and regulators. And it became so deeply entrenched””and was making people so much money””that warnings about its limitations were largely ignored.

Then the model fell apart. Cracks started appearing early on, when financial markets began behaving in ways that users of Li’s formula hadn’t expected. The cracks became full-fledged canyons in 2008””when ruptures in the financial system’s foundation swallowed up trillions of dollars and put the survival of the global banking system in serious peril.

David X. Li, it’s safe to say, won’t be getting that Nobel anytime soon. One result of the collapse has been the end of financial economics as something to be celebrated rather than feared. And Li’s Gaussian copula formula will go down in history as instrumental in causing the unfathomable losses that brought the world financial system to its knees.

The rest of the article is worth reading.

The other factor was the willingness of the rating agencies to “rent” their credibility. There were people who feared that the whole system would come tumbling down but several were punished by being removed from boards after complaints by the rating agencies and others. They were making too much money to stop and worry about risk.

After all, they were too big to fail. The political-financial nexus needs to be broken but it is very powerful. Secretaries of the Treasury were a revolving door with Wall Street. They were there because they were supposed to know the most about the business. That turned out to be questionable.

Here’s another account of the Bush years and the financial crisis.

This comment is long enough so I won’t quote that article. Peter Wehner is the one who was removed from a board because of his warnings.

MK…basically, MBAs with IQs of 125, advised by PhDs with IQs of 140, made mistakes that would never have been made by an old-line loan officer with an IQ of 115.

A big part of this being the difference between making decisions about individual cases involving known people, and making decisions about large aggregates of anonymous data.

Mathematical models are very useful, but also very dangerous when treated as gospel–especially by people who have a strong motivation to believe the results.