This is my first time reading On War, and I have to say that I am so far impressed with the relative ease with which Clausewitz can be applied to modern situations. Book I serves us well not only as an overview of the entire work, but also provides the reader with good baselines, defining fundamental concepts with simple language and examples that I presume would make it possible for the completely uninitiated to understand.

What I find most fascinating though is the high level of Clausewitzian thought found in Marine Corps culture, and I would guess (hope) to some extent in the cultures of other US services as well. I am not certain whether this is by conscious intent, or rather a coincidental development stemming from the Corps’ history and role, but several examples were immediately obvious to me as I read.

Clausewitz Roundtable

Clausewitz, “On War”, Book 1: Jason Bourne and ‘friction’

Last night I watched “The Bourne Ultimatum”, the film about renegade assassin Jason Bourne. In the climax, CIA operative Pamela Landy is faxing a bunch of documents that expose a conspiracy within the agency. She’s racing against the clock – a renegade CIA chief is about to break down the door. Just as the bad guy bursts in, pistol in hand, the last document is sent safely on its way.

If you’ve ever had to fax stuff in a hurry, you’ll know that in real life it never works this way. The machine is turned off, or in power-saver mode. It takes its own sweet time to warm up. It’s out of paper. You punch in the wrong number, or forget to dial an outside line. Then an error message appears. Finally the paper feed jams…

Clausewitz, On War, Book I.: A Man of His Time or for All Times?

Should we still read Carl von Clausewitz?

I am by training, a historian and that education leads me, when I am reading great books like On War, to ask fundamental questions about them as I read – “Is Clausewitz the last, best and final word on the nature of War?” or ” How far did Clausewitz see and where was he blind?”. Such training also inclines me to pay closer attention to the cultural and historical context in which seminal works emerged.

Should American officers today be leading troops or planning campaigns without having had the benefit of the lessons Clausewitz can teach? Supposedly, Moltke the Younger and his generation of officers on the Grossgeneralstab disdained to read Clausewitz(1) but given the results of the Great War, it is reasonable to assume that they and Imperial Germany might have profited from the exercise.

It is is difficult not to be impressed with the brilliance of Clausewitz’s insights as I read Book I. His disciplined yet speculative mind was not constrained by the Newtonian paradigm that governed the 19th century’s increasingly deterministic understanding of nature; nor did he become intoxicated by the mythic Romanticism that pervaded European elite culture and abandon the rigor that can be found on every page of On War. There is ample evidence to be found in Book I. of Clausewitz surpassing his times to grasp concepts and truths that do not emerge in other fields for decades or more than a century.

Yet there are also passages that show the rootedness of the worldview of a European military officer who survived the cataclysm of the Napoleonic wars. I finished Book I. firmly convinced of Clausewitz’s genuine greatness as a philosopher but remain unconvinced that that he has discovered the eternal nature of war in all it’s varied manifestations – I am also deeply skeptical that such a thing could even be possible.

Clausewitz, On War, Book I: War is a Buffet. Eat Up.

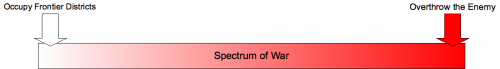

Clausewitz teaches the faithful that war is a spectrum. He identifies several points on this Spectrum of War. Here’s two from his note of July 10, 1827:

War can be of two kinds, in the sense that either the objective is to overthrow the enemy—to render him politically helpless or militarily impotent, thus forcing him to sign whatever peace we please; or merely to occupy some of his frontier districts so that we can annex them or use them for bargaining at the peace negotiations…the fact that the aims of the two types are quite different must be clear at all times, and their points of irreconcilability brought out.

Clausewitz, On War, Book 1: War as a Single Short Blow

(UPDATE: beaten like a rented mule by Cheryl Rofer; see https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/6619.html)

Apologies in advance for exceeding the recommended “above-the-fold” limit:

If war consisted of one decisive act, or a set of simultaneous decisions, preparations would tend toward totality, for no omission could ever be rectified. The sole criterion for preparations which the world of reality could provide would be the measures taken by the adversary — so far as they are known; the rest would once more be reduced to abstract calculations.

… if all the means available were, or could be, simultaneously employed, all wars would automatically be confined to a single decisive act or a set of simultaneous ones — the reason being that any adverse decision must reduce the sum of the means available, and if all had been committed in the first act there could really be no question of a second.

— Carl von Clausewitz, On War (Book I [On the Nature of War], Chapter 1 [What is War?], section 8 [War Does Not Consist of a Single Short Blow]), 1832

At what point shall we expect the approach of danger? By what means shall we fortify against it? — Shall we expect some transatlantic military giant, to step the Ocean, and crush us at a blow? Never! — All the armies of Europe, Asia and Africa combined, with all the treasure of the earth (our own excepted) in their military chest; with a Buonaparte for a commander, could not by force, take a drink from the Ohio, or make a track on the Blue Ridge, in a trial of a thousand years.

— Abraham Lincoln, Address to the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois, 27 January 1838

Time-of-flight equation for a ballistic missile:

t – t0 = √a3/ µ [2Ï€ + (E – e sin E) – (E0 – e sin E0)]

— Bate/Mueller/White, Fundamentals of Astrodynamics (Dover, 1971)

Having deliberately refrained from reading any of the other roundtable contributions so far, lest I become overwhelmingly intimidated, resign from my contributor status, and tell Lex to forget he ever heard of me, I have decided to comment on one very small portion of Book I, specifically Chapter 1, section 8 (page 79 in the edition we are reading). Because, of course, for an American baby boomer, no war that directly affected the entire population was, prior to the late 1980s, expected to be anything other than a single short blow.

So, with the sure knowledge of my limited qualifications ever before me, and the entirely unmanaged risk of merely restating, and poorly, what someone else has already said, I begin …