In researching old, on-line, US Army records on the use of flame throwing tanks and napalm bombs by US Army forces in 1945, Luzon, Philippines fighting. I found a 15 March 1945 report by the US Sixth Army Chemical Warfare officer. He stated that some time between 03 Feb thru 03 Mar 1945 — during the bitter urban fighting between American troops and a combination of Japanese naval base troops and three Imperial Japanese Army infantry battalions of the Shimbu Group — Japanese troops attacked troopers of the American 1st Cavalry Division with hand held and 75mm gun fired chemical munitions.

The Japanese crossed the chemical warfare threshold in World War 2.

See:

Report of the Luzon campaign, 9 January 1945 – 30 June 1945 in four Volumes, Volume III.

REPORTS OF GENERAL AND SPECIAL STAFF SECTIONS

Annex No. 2 Annex 5 to Adm 0 17,

Chemical Plan

ANNEX N O. 2

HEADQUARTERS SIXTH ARMY

A. P. O. 442

0800 15 March 1945

Page 93

1. Enemy Chemical warfare Activities.

Catured enemy toxic munitions on Luzon to date consist of tear gas (CN), vomiting gas (DC), and Chlorpicrin (ps). Isolated instances were reported of the use of tear gas and vomiting gas in the form of self projecting gas candles and artillery shells against elements of the 1st Cavalry Division in Manila. Indications are that the employment of these munitions was against the policy of the Imperial Japanese Army as no large scale coordinated attack utilizing available toxic munitions was attempted. The gas was employed by fanatical suicide squads defending the city. The enemy is capable of using blister gas in chemical land mines only. In case of such action. The contaminated areas must be by-passed as no protective clothing will be carried into the operation.

And American military commanders choose not to retaliate…immediately.

But they did plan to retaliate.

The senior officers who planned Operation DETACHMENT, the invasion of Iwo Jima in Feb 45, had agreed to attack the island with gas first.

It was to be struck by a combination of the naval gun bombardment from landing ships LCI(M) mortar gunboats fitted with Chemical Warfare Service 4.2 inch chemical mortars (US naval guns lacked shells with lethal gas filling) and air delivered M47A1 100 lb bombs carrying phosgene and mustard gas.

This gas bombardment was personally vetoed President Roosevelt, who died two months after Iwo Jima.

When I first read about that Roosevelt veto, I had wondered why it was necessary. The USA had a chemical warfare “No-First-Use” policy in WW2. The American military did not initiate what we call “weapon of mass destruction” attacks independent of specific political authorization then, any more than they would today.

What this Sixth Army document means is that President Roosevelt didn’t veto American chemical warfare _first use_ at Iwo Jima by the US military.

He vetoed American Military RETALIATION.

The Japanese were buck naked in terms of Chemical defense versus an American mustard gas attack.

None of their cave or pill box positions had pressurized collective protection against chemical attack by persistent chemical agents.

After a mustard gas attack all their non-canned or air-sealed food, their water sources, all their weapons, and all their ammunition would be contaminated without enough protective clothing or decontaminating agent to make them usable. And mustard gas often stayed active in bomb proof dug outs in World War One for more than a week after it had dissipated in the surface.

Had we used gas, our Marines would have gone into Iwo Jima standing up, with most of our casualties being from serious heat exhaustion and burns from our own persistent blister agents.

I consider the passage I quoted above as a master piece of understatement and misdirection in light of the follow up request in the same annex, directing that the following be reported in the event of a future Japanese gas attacks:

c. In the event of the actual use of gas, a complete report is desired stating

weather conditions;

terrain features;

amount and kind of war gas used;

method of attack;

number of projectiles;

location of areas affected;

date and time of attack;

number and description of casualties (photographs if possible);

and any other pertinent data procurable.

Note that passage I found on the 1st Cavalry gas attack only answered, marginally, two of the requested 11 factors in the requested attack report template.

Nor did it list whether the “suicide squad” and its weapons were Japanese Navy or from one of the three Japanese infantry battalions the local IJA commander of the Shimbu group left to support the Navy.

The phrase “any other pertinent data procurable” means things like the uniforms of dead suicide troops, AKA were they Japanese Army or Navy.

The Navy commander in Manila was in mutiny to General Yamashita’s orders, but if the chemical munitions were from the Japanese Army, and used by Army troops, it makes Yamashita’s death sentence in a war crimes trial much more understandable.

It now looks like the “hypothetical” chemical weapon attack on Iwo Jima described in the CWS Green Book series was in fact a description of the chemical retaliation plan we were going to use at Iwo Jima, and that Pres. Roosevelt vetoed.

It also makes the “Further topics not covered in the minutes” for the June 18, 1945 meeting between Truman and the JCS over approving both the use of the A-bomb and the Invasion of Japan to take place if the A-bomb failed, take on much darker tones.

Especially in light of;

1) The gas attack plan military historians Norman Polmar and Thomas Allen found in 1995 (and Tom Holsinger wrote about over at Strategypage.com) that now looks certain to have been briefed then,

2) General Marshall’s comment about the use of gas against fortified Japanese islands, and

3) MacArthur’s criticism of the USMC casualties on Iwo Jima.

Any number of very important historical questions come to mind based on this attack happening.

Here is one for you to consider:

Was General MacArthur’s shot at the number of USMC casualties on Iwo Jima a political marker being laid down against the future. A marker that got him the supreme command for the Invasion of Japan from Pres. Truman?

MacArthur accused of played political games with the Republicans to pressure Roosevelt to sign off on the Philippines invasion instead of Formosa invasion that the Joint chiefs of Staff preferred.

Doing the same thing with a Japanese gas attack and the high casualty fiasco at Iwo Jima seems right up his alley.

One more thing.

The American Army over ran a significant, but unnamed amount of Japanese chemical weapon stocks in Leyte.

I have read a large number of histories of the 1941-45 Pacific War, and this was the first time I had read anything like this:

HEADQUARTERS SIXTH ARMY

A.P.O. 442

2300 3 December 1944

Annex No. 1 Annex 5 to Adm 0 16,

Chemical Plan

Page 91

1. Enemy Chemical Warfare Activities

The Jap Leyte garrison was prepared both Offensively and defensively for gas warfare when American forces landed. Munitions filled With tear gas (CN). vomiting gas (DC) and nerve poison (AC) were found in captured ammunition dumps. PWs stated that all unit from companies up were supplied with toxic munitions, including 75mm blistering gas (H or H-L) filled shells. Captured documents reveal that orders were issued in July 1944, to all troops in the LEYTE area to the effect that special smokes and other gas munitions would not be used without a special order and that in View or the Allies’ preparedness to resort to chemical warfare no excuse would be given them for retaliation. It may be inferred that a decision by the Japanese on whether or not to use gas will be based entirely upon strategical considerations.

I said in the comment section of my first Okinawa 65th anniversary post that academics were ignoring post-Cold War declassified documents about the end of gas warfare at the end of World War Two.

What I never expected was to personally find something this big to underline that fact.

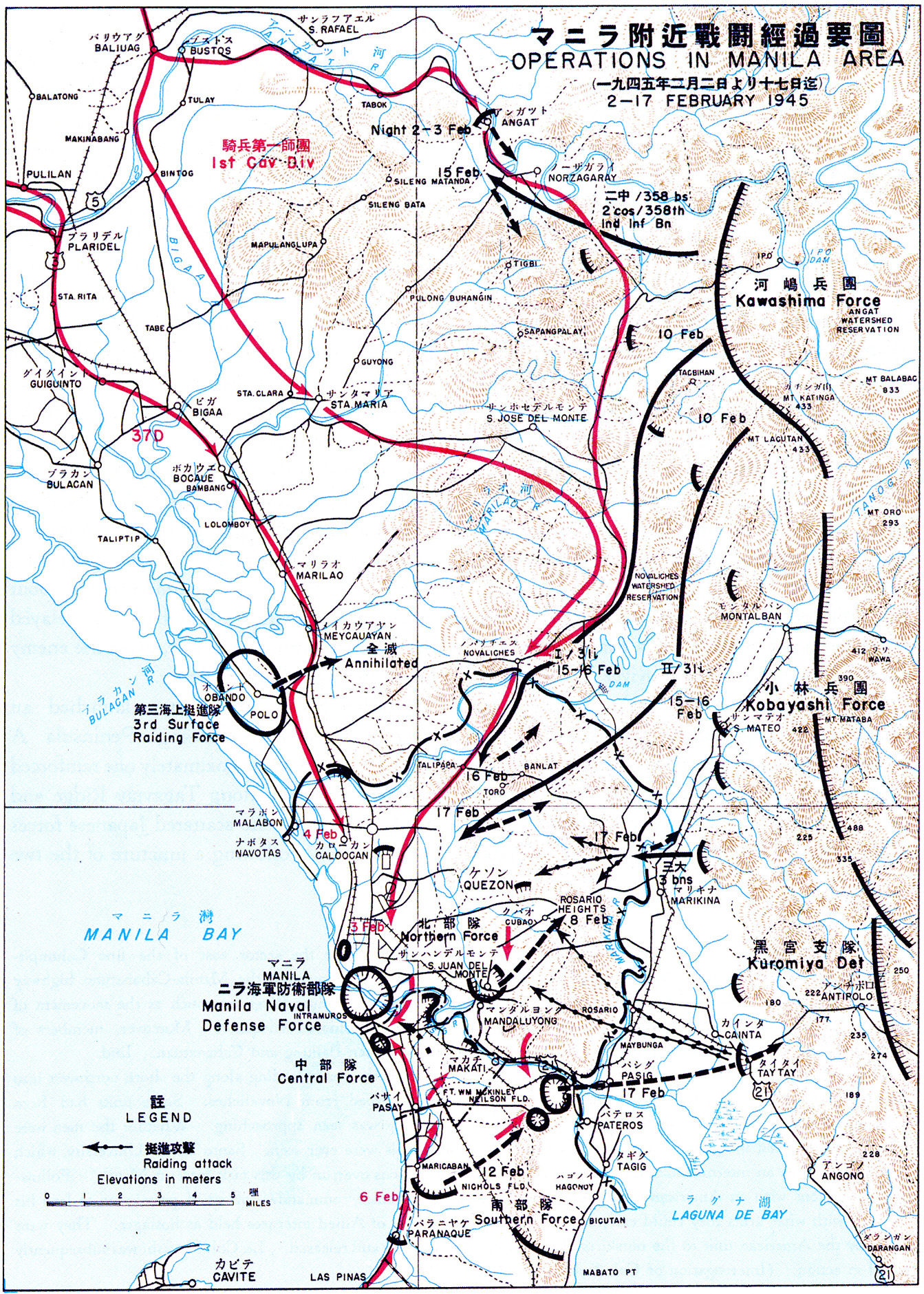

A Japanese Map of the Battle of Manila, 2 February-17 February 1945

I don’t know if the people of the day would consider non-lethal “annoyance” gasses a chemical weapon requiring a retaliatory response. Such non-lethal gasses where used occasionally by all sides in the war. Many smoke munitions could be classified as irritants if used heavily.

Besides, being to quick to respond to a single minor, unplanned provocation would undermine deterrence. If the other side believes that the least mistake on their part will provoke a chemical attack, they have a greater reason to believe they will face a significant attack first and that therefore they should attack first.

I think there were three major practical reasons why chemical weapons were considered a last resort in WWII. (1) Against prepared troops, chemical weapons simply aren’t to effect. (2) In most cases, the CW present as big a danger to the side using them as it does to the target side. (3) In fast moving, mobile warfare, chemicals aren’t as useful. Targets simply move away. (4) The saturation threshold is relatively low such that a small outnumbered force can chemically hit a large force just as hard as the large force can hit the small force. This last means the large force has no incentive to use CW first and that CW can’t help the smaller force get an edge.

The major reason however, was the prospect of staggering civilian casualties. The trench warfare of WWI, for all its horrors, was a contest between soldiers. Civilians were kept well back of the front lines. In the mobile warfare of WWII, the use of chemical weapons would have meant dozens of civilian deaths for every soldier killed. It is not impossible that fighting near major urban areas could have killed hundreds of thousands in mere hours.

We could have certainly saved the lives of Americans during the Island campaigns by using gas but we could have done so only by completely exterminating the civilian population. Bombing cities was hard enough but at least the vast majority of the people in the cities survived. With gas, there wouldn’t have even been insects left.

Shannon,

Chloropicrin was not a non-lethal “annoyance” gas. By itself, it is highly toxic. It was typically used a cocktail with other war gases because on its own it caused vomiting (AKA a lacrimator), blindness and lung damage.

It’s delayed effect mean that you could dose troops with it, induce vomiting and then hit them with more lethal agents when they could not properly mask up. The Italians were victims of this type of attack in 1917.

Unlike phosphine or mustard agents, it was weather independent in its effects.

The Chinese were repeatedly victims of “smoke candles” dispensing this agent in the 1937-45 Sino-Japanese war.

This is the MSDS posted on wikipedia:

Safety

Chloropicrin is a highly toxic chemical: NIOSH 1995 states that:

* Chloropicrin is a lacrimator and a severe irritant of the respiratory system in humans; it also causes severe skin irritation on contact. When splashed onto the eye chloropicrin has caused corneal oedema and liquification of the cornea.

* Exposure to concentrations of 15ppm cannot be tolerated for more than 1 minute, and exposure to 4ppm for a few seconds is temporaily disabling.

* Exposure to 0.3-0.37 ppm chloropicrin for 3 to 30 seconds causes tearing and eye pain. Exposure to 15ppm for a few seconds can cause respiratory tract injury.

* Exposure to 119ppm in air for 30 minutes is lethal; death is caused by pulmonary oedema.

Examples of industrial exposure in humans: 27 workers in a cellulose factory who were exposed to high levels of chloropicrin for 3 minutes developed pneumonitis after 3 to 12 hours of irritated coughing and difficulty on breathing; they subsequently devloped pulmonary oedema and one died.

EU classification of chloropicrin is: R22 Harmful if swallowed, R26 Very toxic by inhalation, R36/37/38 Irritating to eyes, skin and respiratory system, R43 May cause sensitisation by skin contact, R50/53 Very toxic to aquatic organisms, may cause long term adverse effects in the aquatic environment.

Because of chloropicrin’s stability, protection requires highly effective absorbents, such as activated charcoal.[3] Chloropicrin, unlike its relative compound phosgene, is absorbed readily at any temperature, which may pose a threat in low or high temperature climates.[5]

The use of the substance has been restricted by the US government, although such restriction is outdated now [7]

Trent J. Telenko,

Chloropicrin was not a non-lethal “annoyance” gas. By itself, it is highly toxic.

Anything is lethal at high concentrations. The British accidentally killed Kurds back in the 30s with tear gas. We tossed smoke grenades and shells down tunnels to smoke defenders out. In an enclosed space, the smoke is lethal.

I’ve never seen Chloropicrin categorized as a lethal gas. It has been used in crowd control whereas you would never think of using phosgene or mustard gas.

The major difference between irritants and lethal gasses is that with irritants, the debilitating physical irritation occur at exposures far under the lethal level. Chloropicrin will send people to their knees upchucking their socks at exposures way, way under lethal levels.

With lethal gasses, by the time you feel their irritation effects, you have already been exposed to a potentially lethal dose.

In my youthful recklessness, I made a bunch of chlorine in my home lab. I had a break in my apparatus and doused my self with chlorine gas. It barely caused any irritation at all. I didn’t pay it any mind until the next day when I started coughing up huge amounts of clear fluid from my lungs and my chest hurt like hell.

Phosgene and mustard gas are even worse. You can receive a lethal dose of mustard gas without even knowing you were exposed. The most dangerous place to be in a mustard gas attack was on the periphery or downwind where you couldn’t see the actual munitions detonating. People just started coughing and clawing at their eyes. Even if they got their mask on, it was to late. One of my great-great uncles was maimed in just such an attack.

I don’t think anyone in WWII, especially the veterans of WWI, would have classified Chloropicrin as a lethal gas. Even if they did, I don’t think they would have gassed an entire island in retaliation for one unauthorized use of the gas at another battle.

If the Okinowa planners had had any idea what was in store, I think they would have plastered the defenses with chemicals.

If we had invaded Japan, we would have thrown everything we had at them, after the Okinowa experience.

Shannon,

Your reactions to the Japanese use of CHLOROPICRIN is colored by your knowledge of its use as modern crowd control agents.

You need to read more WW1 histories on gas warfare.

CHLOROPICRIN was one of the two most common suffocating agents fired by the Imperial German Army at American troops in WW1, the other being PHOSGENE. Point in fact, these agents were usually fired together in the same barrage.

Given what happened to american troops 28 years earlier, any use of CHLOROPICRIN by the Japanese against Americans of 1945 would be seen as a lethal chemical attack.

See:

The Medical Department of the United States in the World War, Volume XIV, Medical Aspects of Gas Warfare

http://www.vlib.us/medical/gaswar/gas.htm

CHLOROPICRIN was both a LACRYMATOR, which means it caused blindness, and a SUFFOCATING GAS.

From the link:

CHLOROPICRIN requires a higher degree of concentration to cause a suffocative action than could readily be obtained in field use. It was frequently used in conjunction with phosgene the enemy hoping that the prompt irritant effect of the chloropicrin would prevent the wearing of the gas mask, thus rendering the soldier an easy prey to the accompanying phosgene.

and

The following toxic substances were most frequently used by the Germans in their chemical warfare: (1) Lacrymators: Benzylbromide. (2) Sternutators: Diphenylchlorarsine. (3) Lung irritants: Chlorine, phosgene, carbon oxychloride, chlormethylchlorformate, bromacetone, chloropicrin. (4) Vesicants: Dichlorethylsulphide, chlorarsines, bromoarsines.

This classification, while eminently practical and convenient, does not imply that some of the gases have no physiological action other than that of their group. This is not true. For instance, bromacetone and chloropicrin, when employed in concentrations too low to affect the lungs, are lacrymators.

and

…For example, a concentration of chloropicrin which is perceptible to the eye in time will injure the lung epithelium, but several days of continuous exposure are required before there is evidence of the development of lung edema. The effect on the eyes, however is instantaneous, suggests a physical or a molecular effect, and is a striking example of specificity. The time element precludes the possibility of hydrolysis or other decomposition, and suggests that this compound is itself a protoplasmic poison with a particular chemical relation to the compounds of the corneal nerve filaments, so that these are stimulated long before other nerve endings or other types of tissue cells are affected. After prolonged exposure, recognizable only in the eye, the respiratory mucosa shows definite injury, and rhinitis, bronchitis, pneumonia, and lung edema develop. At a still later period the kidney also shows injury. Chloropicrin is evidently toxic, therefore, to many tissues. As is well known, it is quite stable chemically, and hydrolyzes only very slowly in water. It is soluble in the fat solvents and the fats. Like chloroform, it is picked up by the blood stream from the lungs, and because of a certain degree of tissue specificity it reaches and damages the kidney more perceptibly than the liver, muscles, nerve cells, or other types of tissues. In this it resembles its chemical relative, chloroform, whose specific action on the liver is well known.

and

The action of chloropicrin on the respiratory tract has already been touched upon. At moderate concentrations it produces lung edema, intense irritation of the whole tract, violent coughing, and retching. The edema comes on with considerable delay after exposure. Chloropicrin hydrolyzes very slowly in water, so that its effect on the respiratory mucosa can hardly be attributed to a production of hydrochloric acid within the cells, though this factor may contribute in the delayed action. A very general injury to the whole organism is suggested in the fact that men exposed to this gas are described as aging quickly, though the kidney lesions may account for part of this general deterioration. Nothing at all definite is known concerning the chemical action of this gas on protoplasm.

Shannon,

The US government as a policy choice decided to bury 1930’s and early 1940’s Japanese lethal chemical warfare use in China much the same way it ignored Iraqi chemical warfare against Iran in the 1980’s.

I found the following, which references a recently declassified War Department document “File I.B. 152-A.”

This is what a Japanese researcher found after he read it.

See:

http://chinajapan.org/articles/07.1/07.1wakabayashi3-33.pdf

Considering all of this, the most thought provoking issue emerg- ing from File I.B. 152-A has to do with official American attitudes toward Japanese chemical warfare. Copies of this file were distributed to the President, the Secretary of War, the Chief of Staff, the State Department, General Headquarters, and other high state officials. Assuming that the file was read, many people at the highest levels of both the United States Government and military must have been privy to its contents.

In November 1941, then, American officials knew when, where, and

to what effect Japan was using poison gas in China; and they projected that an escalation in this chemical warfare might take place at any time. Even allowing for a degree of skeptical detachment and for the usual dryness of bureacratic language, File I.B. 152-A discloses a remarkable lack of American concern for China’s plight. The opening comments in Miles’s “Memorandum for the Chief of Staff,” for example, would hardly inspire a Frank Capra movie.

Hence, the overriding question posed by File I.B. 152-A is: How

should we comprehend this seeming American nonchalance? It cannot be explained solely by the fact that the United States was not yet at war with Japan. Well before Pearl Harbor, the US Government was using the issue of Japanese aggression to justify imposing trade sanctions against Japan, and the American mass media were leveling intense moral criticism at other Japanese attrocities in China. Japanese chemical warfare.would seem to present an ideal issue to be exploited for those purposes.

and

The issue of Japanese chemical warfare against China was swept under the rug at the Tokyo War Crimes Trials despite ample evidence presented by US prosecutor Thomas H. Morrow. Morrow submitted a detailed report entitled “A General Account of Japanese Poison Warfare in China, 1937-1945”– a report that incorporated the contents of File I.B. 152-A. His arraignments took place for two days in August 1946, but then he was Suddenly returned to the United States without explanation; and the issue of Japanese chemical warfare was dropped from the proceedings. After the Tokyo War Crimes Trials ended, this issue received scant attention from historians; and, as a result, many general accounts of warfare in the twentieth century still mistakenly assert that poison gas was employed only in World War I.

It is fairly easy to understand why the US and other Allied

Powers after 1945 were disinclined to condemn Japan for perpetrating chemical warfare. The Americans themselves had already practiced atomic warfare and were contemplating the use of chemical defoliants against Japan when the war ended. Later, at the Tokyo Trials, US Occupation officials granted immunity from war crimes prosecution to the leaders of Kwantung Army Unit 731 in exchange for top-secret information on biological Warfare. All of this made it awkward Americans for to cast the first stone. Furthermore, we now know that the Soviet Union deployed–and presumably planned to use–chemical weapons

such as iperito on the Far Eastern front. Indeed, Soviet poison

gas factories continued to operate in the postwar era; and the Soviet Navy, for lack of a better disposal method, dumped some 30,000 tons of these chemical weapons into the Sea of Japan. 8

However, the question of why America and the other Allied Powers

remained silent about Japanese chemical warfare against China during the war awaits a clear answer. Aside from raising this particular problem, the declassified US military intelligence file reproduced below may provide some preliminary clues for solving it.

And this is one of the documents in I.B. 152-A

CONFIDENTIAL

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE

I.B. 152-A

JAPANESE USE OF POISON GAS IN CHINA

INTELLIGENCE BRANCH

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE DIVISION

WAR DEPARTMENT GENERAL STAFF

TAB B

Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, Washington, D. C.

No. 9730

Office of Military Attache

AMERICAN EMBASSY

Peking, China

February 9, 1939

Subject: Chemical Warfare in China

1. The enclosed letter and documents, the latter with translations,are forwarded in connection with reports of use of gas by the Japanese Army in China.

2. I doubt the assumption that the Japanese have used chlorine, although my opportunities for investigation have been very limited, I am satisfied that they have used tear and sneezing gas on many occasions, and also some kind of an irritant smoke.

3. Analysis by the British of a sample of gas used by the Japanese on the Yangtze front showed that it was a very volatile

toxic smoke with a lung irritant effect. The chemical name is DIPHENYL-CYANOARSINE, formula (C6 H5) Cn As. It is mixed with pumice stone to get a slow-burning effect. In the sample analyzed, twenty six ounces of chemical were mixed with one pound and ten ounces of pumice.

/s/ Joseph W. Stilwell,

Joseph W. Stilwell

Colonel, Infantry

Military Attache