When I started writing my “History Friday” columns, one of my objectives was to explore the “military historical narratives” around General Douglas MacArthur, so I could write with a better understanding about the “cancelled by atomic bomb” November 1945 invasion of Japan. One of the least explored aspects of MacArthur’s fighting style was his highly flexible approach to logistics, which he described as “We are doing what we can with what we have.” Logistics being the ability to transport and supply military forces. In describing MacArthur’s flexibility, and poor documentation of same, I wrote previously:

“One of the maddening things about researching General Douglas MacArthur’s fighting style in WW2 was the way he created, used and discarded military institutions, both logistical and intelligence, in the course of his South West Pacific Area (SWPA) operations. Institutions that had little wartime publicity and have no direct organizational descendent to tell their stories in the modern American military.”

The importance of logistics is the reason for the adage, “Amateurs talk tactics while professionals talk logistics.”

Today’s column is the story of one of those many “throw away” logistical institutions. In this case, it was MacArthur’s “human porter logistics” — native workers provided by the Australian and Dutch East Indies colonial authorities — married to the 5th Air Force’s primitive bootleg radio beacon navigation. A mid-20th century great-great-grandfather of today’s Global Positioning System radio beacon satellites.

The story of MacArthur’s “Human Porter Logistics” comes by way of the 1955 book “CAVES of BIAK – An American Officer’s Experiences in the Southwest Pacific” by Harold Reigelman, a retired reserve US Army Colonel who was a Corps Level staff officer in the US Army I Corps during World War 2 (WW2). Reigelman had been a pre-war politician/Lawyer in New York City and was a practicing Jew. He had an eye for detail and a smooth written “voice” that made his book part combat story, part travelog, part military lessons learned training manual. I learned more about the functioning of a Corps level staff officer during combat than in any other book I have read on WW2.

That eye for detail yielded up the following bit from page 26 of “Caves of Biak” on MacArthur’s logistics I have never seen in print anywhere else in decades of readings on WW2:

Natives were supplied in work groups by headmen. They were paid with rations, plus two twists of tobacco and ten shillings monthly. For this they cleared the jungle, built shacks; corduroyed, graded and ditched the roads; and hand-carried over trails passable only afoot. A three-day carry-load was sixty pounds, of which forty was food for the carrier and twenty, “pay-load.” To supply 3,000 troops six days’ journey from base required forty-one hundred carriers. Of each 7,000 pounds started from base only 350 pounds would reach the troops. The balance was food for the carriers. The pay-load increased as the length of the journey decreased.

That works out to only 33% useful payload fraction for a 3-days march and a 5% useful payload fraction of every pound or kilogram of supply sent forward with porters after a six days march to front-line allied troops. That three or six days march is only from the start line to where the troops are. For the Porters, those are six-day and 12-day round trips respectively. Round trips where they often took back wounded as well as took forward food.

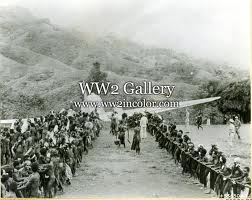

Now you know why the Kokoda Trail, and the Battle of Buna, were such ordeals for the troops involved. (See photo below)

The other half of this logistical solution comes from General George Kenney’s book “The MacArthur I Know.” This passage is from pages 71 and 72:

Over at Port Moresby the transport pilots worked out a scheme of dropping supplies in bundles of 300 pounds, each with a parachute attached; this method could be used in bad weather. Flying on instruments, just as if he were in a fog, the pilot flew toward the airdrome radio station, using his radio compass for direction. When the plane passed directly over the radio station, the needle of the compass flipped and at that moment the pilot signaled the man in the rear of the airplane to shove the bundle with its attached parachute out the door. The plane would then circle and keep repeating the performance until the whole cargo had been delivered. I had watched a test during which sixteen bundles had been dropped from an altitude of 2,500 feet, while the pilot was flying hooded and entirely by instrument. The bundles had all fallen inside a circle one hundred yards in diameter.

This delivery tactic was used to resupply the 32nd Division troops at Buna in 1943 and saved the invasion after three days of bad weather cut off food resupply. Once this tactic was available, it was later used by Kenney for his most famous deception operation of the war, The destruction of Japanese air power at Wewak. The following is from pages 252-253 of “General Kenney Reports – A Personal History of the Pacific War”:

Squeeze Wurtsmith said he would like to fly up there the next morning in a P-40 and take a look at the place. I told him to go ahead but to have someone else follow him with an A-24 two-seater, which could land and take off in a much shorter space than a P-40. That would give him a chance to get home, in case the P-40 cracked up or the field was not long enough or good enough to attempt a take-off. I told Squeeze to load up the empty back seat of the A-24 with trade goods to give the natives a good start on preferring our business to dealing with the Nips. Lieutenant A. J. Beck took the A-24.

.

The next day General Squeeze Wurtsmith and Lieutenant Beck landed at Marilinan and made a complete reconnaissance of the whole area. The old strip could be lengthened a little more but would only be satisfactory for cargo airplanes like the DC-3.

.

Wurtsmith had to have some more grass cut to get off as the natives had cut only about I 200 feet. Squeeze claimed he made the shortest landing ever made with a P-40. However, four miles north of Marilinan, at a little village called Tsili-Tsili, they found an excellent site, which looked as though it could be made into an airdrome with double runways 7000 feet long and with plenty of room for dispersed parking areas.

.

Whitehead had been wanting for some time to build an airdrome up near Bena Bena at a place called Garoka. We didn’t have the cargo planes to support a real show up there but I told Cooper to send someone to Garoka and get the natives to start clearing a strip right away. I didn’t care about making anything more than a good emergency field, but I wanted a lot of dust raised and construction started on a lot of grass huts so that the J aps’ recco planes would notice. Also I ordered some indications of activity at Bena Bena itself and told Cooper to be sure to explain to the natives that we were playing a good joke on the J aps, that we were trying to get them to send some bombers over. If the Nip really got interested in the Bena Bena area, he might not see what we were doing at Marilinan. In about a week I figured the Nip should get worried and start bombing.

.

In the meantime, we would fly into Marilinan enough Aussie ground troops to cover all the trails coming into the area and then move in the 87 1st Airborne engineers to build the main base at Tsili-Tsili. Squeeze liked that name but both Cooper and I liked the sound of Marilinan better. Besides, Tsili-Tsili might have suggested to some people that it was descriptive of our scheme of getting a forward airdrome.

Kenney’s deception worked even better than his radio beacon air drop plus human porter logistics. Wewak was eliminated and that opened the gateway to a sustained six week air campaign that, with assistance from Admiral Halsey’s other pincer in the Operation Cartwheel offensive, destroyed Rabaul as the key forward base for Japanese power in the South Pacific.

And now you know about another logistical institution that MacArthur used and was later forgotten in the official institutional narratives of WW2.

Sources and Notes:

George C. Kenney, The MacArthur I Know, Copyright, 1951,DUELL, SLOAN AND PEARCE, New York, Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 51-10404

George C. Kenney, “General Kenney Reports – A Personal History of the Pacific War” published: New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1949. 1987 & 1997 reprints, Air Force Historical Studies Office, AF/HO,1190 Air Force, Pentagon,Washington,DC, 20330-1190, ISBN 0-912799-44-7

Harold Riegelman, Colonel U.S. Army Res. (RET.) “CAVES of BIAK – An American Officer’s Experiences in the Southwest Pacific” WITH PREFATORY NOTES BY GENERAL ROBERT L. EICHELBERGER AND AMBASSADOR HU SHIH, The Dial Press, NEW YORK: 1955

Your premise that units that had no descendants are under-recorded is proving pretty fruitful.

Trent, when you finally publish your essays into a book, I will be the first in line to buy one. Excellent research. How long have you been doing your legwork on Mac Arthur’s SW Pacific command?

That is a wonderful photo.

Dearieme,

People and institutions have patterns of behavior. They like to talk about themselves and their past successes.

No current military institution equals unknown military history, because there isn’t a “Someone” who can talk about itself.

Once you know that pattern, it makes interesting military history research and writing easy.

Joe,

Tom Holsinger, knowing both my interests and my obsessive-compulsive tendencies, gave me a copy of “Hell to Pay: Operation Downfall and the Invasion of Japan, 1945-1947” by D. M. Giangreco the winter of 2009.

It was pretty much a compulsive down hill from there.

Tom H,

Which photo?

Last photo, of the Papuan natives in full rig towing the C-47 out of the jungle.

Striking how “buffed” or “cut” the native physiques are, without a gym on the island, only their native “life style”

FYI, the A-24 mentioned by Kenney is the Army version of the S.B.D. Dauntless Dive Bomber.

[The above is a “tongue-in cheek” comment]

Richard,

“Striking how “buffed” or “cut” the native physiques are, without a gym on the island, only their native “life style”… [The above is a “tongue-in cheek” comment]”

What’s tongue-in-cheek? When we were in Chiapas state in Mexico in the late ’70s, doing field training, the village headman set me up to try to carry a normal-sized (for them!) load a firewood using a tumpline. Now I’m a fairly short guy–5’6″–but I towered over the men in the village, and as for the women, I think any of them could have walked under my outstretched arms.

But this load of firewood–the sort of thing all the guys there carried routinely–well, all I can say is it required the utmost effort for me to raise it off the ground at all, and my staggering gait from there provided and immense amount of amusement to one and all…

Richard, Kirk,

Gary Taubs approves your messages.

There’s gym muscles and work muscles.