John Hussman on valuations

The saga of Broker Joe, from 2007

Some Chicago Boyz know each other from student days at the University of Chicago. Others are Chicago boys in spirit. The blog name is also intended as a good-humored gesture of admiration for distinguished Chicago School economists and fellow travelers.

John Hussman on valuations

The saga of Broker Joe, from 2007

A CFTC report explains that open interest in long-dated NYMEX West Texas Intermediate crude oil futures continues a long-term decline.

That’s because oil extraction has become more efficient in tight oil fields compared to conventional wells and producers have more flexibility in turning on and off the taps in response to oil prices.

The increasing amount of crude coming in from tight oil in portfolios of production firms has left them with less crude to sell five or more years forward, reducing their need for long-dated futures contracts, according to the study. U.S. weekly production has skyrocketed to 11 million barrels a day, the highest level on record, according to Energy Information Administration data.

Scott, James C. Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

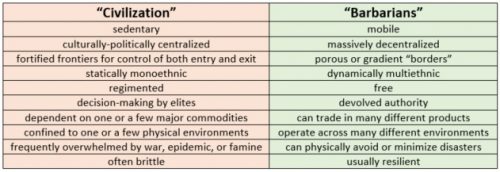

Scott has hit another metaphorical grand slam with this one, a worthily disconcerting follow-on to his earlier work. I have previously read (in order of publication, rather than the order in which I encountered them) The Moral Economy of the Peasant, Seeing Like a State, and Two Cheers for Anarchism, and found them congenial. Scott is particularly good at encouraging a non-elite viewpoint deeply skeptical of State power, and in Against the Grain he applies this to the earliest civilizations. Turns out they loom large in our imagination due to the a posteriori distribution of monumental ruins and written records—structures that were often built by slaves and records created almost entirely to facilitate heavy taxation and conscription. Outside of “civilization” were the “barbarians,” who turn out to have simply been those who evaded control by the North Koreas and Venezuelas of their time, rather than the untutored and truculent caricatures of the “civilized” histories.

By these criteria, the United States of America is predominately a barbarian nation. In the order given above:

Sarah Hoyt’s site has an interesting article entitled The Free Market versus Death Panels. I recommend it in general but it misses one point that I think deserves some examination. There is one exception to the market rule that is so embedded in our social mores that both market and non-market advocates alike pass over it. They shouldn’t. It’s called triage.

I have never met a free market advocate of medicine who does not recognize and accept non-market allocation in terms of emergency care, specifically when medical treatment systems and personnel are overloaded. When you have 10 operating theaters and 50 people who need surgery, who gets in first and who gets in last? The market would institute surge pricing and let the ill or their care circles sort out how much they can wait. Triage orders it so that the fewest number of people die.

It’s an important footnote to recognize triage and to explain *why* that limited exception is ok, properly fenced off with limiting principles so the exception doesn’t swallow the rule, and what is the reason we’re all generally ok with triage causing more suffering and against surge pricing.

First is to note that triage causes excess suffering because it is designed, and functions well at minimizing loss of life at the cost of extending suffering for those condemned to delays in treatment by the triage system. We’ve all made a moral decision that some non-fatal suffering is an acceptable payoff for a reduced fatality count when medical systems are overwhelmed and resources have to be quickly, efficiently deployed to reduce fatalities.

It’s important to cover these things because they take away all the central planner’s best arguments away from them when you reconcile the free market with triage. Solidarity, the common good, human decency, these are the heartstring appeals of the statists who falsely claim that free market medicine will cause wicked outcomes because the market has no sense of solidarity, the common good, or human decency.

These statists are wrong. But they have to be shown wrong. Examining triage is a very good way to do it.

June 2017 T-Bond Futures (Daily)

Multiple choice bond quiz:

1) The fix is in.

2) The longer this continues, the higher the odds of a big move, probably lower in price, after one of the next breakouts.

3) Both 1 and 2.