I hate silliness – bureaucrats wielding power arbitrarily, ignoring consequences, etc. – ask me about our local Home Owners Association, for instance. But this Instapundit link is to a great, productive, tactful moment when analysis, persuasive writing, an understanding of his audience and human nature wielded the power of a leader, appropriate to such rare skills. Many of you (esp. Dan) have a better appreciation of the common bottleneck but even I can see this “impactful” (an ugly word but so appropriate here) of Peterson’s skill. Of course, why this is a “temporary” fix is another question. And why libertarians have a point about minimal control and why a disproportionately (well, disproportionate to the American tradition) strong state often stifles free enterprise.

Organizational Analysis

Pwosesis Ayiti A

No reward for resistance; no assistance, no applause.

— Neil Peart, “Lock and Key”

For none of us lives to himself, and none of us dies to himself.

— Paul of Tarsus, Epistle to the Romans

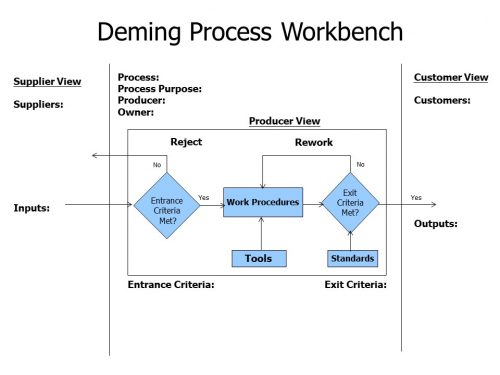

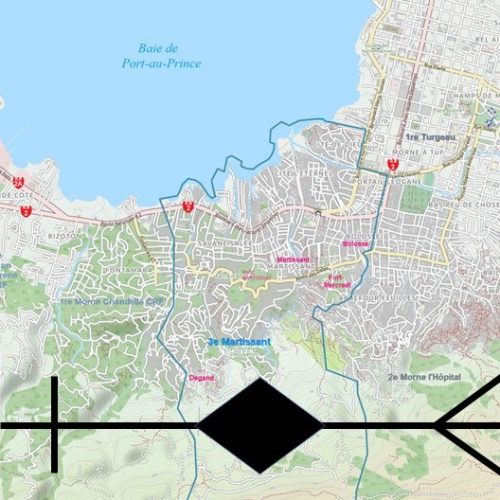

La merde a frappé le ventilateur; my earlier post became abruptly more topical on Wednesday the 7th, when we woke to the news of the assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse. This follow-up will consider the implications of developments since late June and will specifically respond to commenters on Dilèm Aksyon Kolektif nan Matisan. Most of the structure of this post will follow the Deming process-workbench model, because history is, to a great extent, a series of contingent events, and because I am a giant process nerd.

Dilèm Aksyon Kolektif nan Matisan

Generatim discite cultus

(Learn the culture proper to each after its kind)

— Virgil, Georgics II

Stephen Biddle, Nonstate Warfare: the Military Methods of Guerrillas, Warlords, and Militias (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021)

By way of making this more than a merely armchair review, I will be discussing the developing situation of state failure in Haiti, which is providing a personally harrowing example of the phenomena theorized and studied in this book. NB: additional situation reports like the one I quote from below will appear at this OCHA webpage.

I. Increasingly Scale-Free Military Activity in the 21st Century

In this follow-up to 2004’s Military Power: Explaining Victory and Defeat in Modern Battle (also from Princeton), Stephen Biddle continues to elucidate the many ramifications of the one-to-many relationship which came to dominate the battlefield between the Napoleonic Wars and World War I. Over that century and in the decades that followed, individual-service weapons increased in rate of fire from a (very) few rounds per minute to ~10 rounds per second, in effective range from ~100 to >300 meters, and in accuracy from (optimistically) 10 to 1.5 milliradians. Say 2 ½ orders of magnitude improvement in RoF, half an order of magnitude in range, and one order of magnitude in accuracy; multiplying these together to create a sort of index of effectiveness, I get an overall change of 4 orders of magnitude, with stark implications for battlefield environments.

Tiananmen OSINT

“Either write something worth reading or do something worth writing.” — Benjamin Franklin

[Readers are directed to the end of this post for an explanation of my timing and motivation.

UPDATE 6/5, 11 AM CDT: videos embedded!]

I. Anniversary Reconnoiter

At around nine in the morning local time on the thirtieth anniversary of the “June Fourth Incident,” I began a reconnoiter of Tiananmen Square in central Beijing to observe security measures and, if possible, witness any attempt at commemorating the massacre. I accompanied Dr. Andrew R. Cline, professor of media, journalism, and film at Missouri State University in Springfield. We were part of group of eleven people—four students, two faculty, and five others including me—comprising a “Study Away” program from MSU which had spent the previous twelve days in China, flying into Beijing and taking high-speed trains to Xi’an and Xining, then on via the QinghaiTibet railway to Lhasa before flying back to Beijing. Of all days, Tuesday 4 June 2019 was designated a free day for the group: no itinerary—and no guide. The remaining nine group members, as it turned out, had other ideas about what to do that day.

Andy’s motivation was broadly journalistic, garnished with a specific interest in whether any actual Marxists would show up. I went along out of a feeling that I had something of a reputation to uphold, and quickly decided during our approach that I would evaluate the security measures and write up a more quantitative report, although I will also pass along some thoughts about the organizational behaviors involved.

A Sadly Revealing Story

A Houston physician named Dr. Hasan Gokal had a limited quantity of the Moderna covid vaccine to distribute. The vial had been opened, and the vaccine would expire in six hours. He could either find 10 qualified people to administer it to, or just throw it away. He chose the former course, rounding up 10 people, some of whom were acquaintances and others strangers.

For that, he was fired from his job and criminally prosecuted.

Officials maintained that he had violated protocol and should have returned the remaining doses to the office or thrown them away. According to Dr Gokal, one of the officials startled him by questioning the lack of “equity” among those he had vaccinated.

So, if he had just thrown away this scarce and valuable vaccine, he would have been just fine. Because he used his judgment and took action, he lost his job and was prosecuted…the judge threw the charge out for its ridiculousness, but the prosecutor, whose name is Kim Ogg, has vowed to present the matter to a grand jury.

We seem to be moving to a point in America today where the less you do, the better off you are: don’t use your individual judgment, don’t take action without bureaucratic approvals, don’t conduct informal conversations and don’t tell jokes.

I am reminded of the Spanish naval official (see my post here) who in 1797 wrote a plaintive essay on the topic: Why do we keep losing to the British, and what can we do about it?

An Englishman enters a naval action with the firm conviction that his duty is to hurt his enemies and help his friends and allies without looking out for directions in the midst of the fight; and while he thus clears his mind of all subsidiary distractions, he rests in confidence on the certainty that his comrades, actuated by the same principles as himself, will be bound by the sacred and priceless principle of mutual support.

Accordingly, both he and his fellows fix their minds on acting with zeal and judgement upon the spur of the moment, and with the certainty that they will not be deserted. Experience shows, on the contrary, that a Frenchman or a Spaniard, working under a system which leans to formality and strict order being maintained in battle, has no feeling for mutual support, and goes into battle with hesitation, preoccupied with the anxiety of seeing or hearing the commander-in-chief’s signals for such and such manoeures…

Thus they can never make up their minds to seize any favourable opportunity that may present itself. They are fettered by the strict rule to keep station which is enforced upon then in both navies, and the usual result is that in one place ten of their ships may be firing on four, while in another four of their comrades may be receiving the fire of ten of the enemy. Worst of all they are denied the confidence inspired by mutual support, which is as surely maintained by the English as it is neglected by us, who will not learn from them.

I think Don Grandallana would recognize many of the behavior patterns in America today as being the same kind of thing that were so destructive to his country’s chances in battle.

Note that Dr Gokal was questioned about a lack of ‘equity’ in his distribution of the vaccines. “Are you suggesting that there were too many Indian names in that group?” he asked. Exactly, he was told.

Time available for the vaccine distribution was strictly limited; Dr Gokal probably contacted patients and other people he knew and many of them were Indian. Was he supposed to get demographic data for his county and ensure that the people he contacted matched the average statistical profile?

I am also reminded of something written by historian AJP Taylor about the Austro-Hungarian Empire, cited in my post here:

The appointment of every school teacher, of every railway porter, of every hospital doctor, of every tax-collector, was a signal for national struggle. Besides, private industry looked to the state for aid from tariffs and subsidies; these, in every country, produce ‘log-rolling,’ and nationalism offered an added lever with which to shift the logs. German industries demanded state aid to preserve their privileged position; Czech industries demanded state aid to redress the inequalities of the past. The first generation of national rivals had been the products of universities and fought for appointment at the highest professional level: their disputes concerned only a few hundred state jobs. The generation which followed them was the result of universal elementary education and fought for the trivial state employment which existed in every village; hence the more popular national conflicts at the turn of the century.

We are now at the point in America where every possible decision and situation, down to the time-critical administration of vaccines, must be looked at through ethnic lenses. We may be heading for the same kind of creaky and rather dysfunctional society as was Austria-Hungary…and it’s quite possible that the actual outcome will be something much darker.

Lead and Gold cited Sir John Keegan on British impressions of American GI’s who arrived in that country during WWII:

Americans did not defer; that was the first and strongest of the impressions they made. European travelers to the United States had made that observation even in the eighteenth century, and it was made wholesale by British observers of the GIs. In a society which worked by deference, there were many who were shocked by the upstandingness of the individual American soldier. Enlisted men did not know their place, and their officers seemed unconcerned by the free-and-easy ways of their men. Many of the British, who had been taught their place well, found they liked the Americans for their casualness and admired a system of discipline which worked by getting things done. American energy: that was the second impression.

In America today, we seem to have lost much of that spirit. Can we get it back?