I’ve been reading Daniel Walker Howe’s The Political Culture of the American Whigs(1979). It slowly gave me a better understanding, since I started in a complete fog. Like his Making the American Self

, here Howe chooses representative figures to give narrative, character & understanding. Just because the book is forty doesn’t mean insights don’t remain. Howe enlivens the Whigs and reminds us our parties still have more than a bit of the Whig & the Jacksonian. But, surprisingly, an anecdote used to illuminate John Quincy Adams reminds us of a spring candidacy.

Science

Why Doctors Quit.

Today, Charles Krauthammer has an excellent column on the electronic medical record. He has not been in practice for many years but he is obviously talking to other physicians. It is a subject much discussed in medical circles these days.

It’s one thing to say we need to improve quality. But what does that really mean? Defining healthcare quality can be a challenging task, but there are frameworks out there that help us better understand the concept of healthcare quality. One of these was put forth by the Institute of Medicine in their landmark report, Crossing the Quality Chasm. The report describes six domains that encompass quality. According to them, high-quality care is:

1) Safe: Avoids injuries to patients from care intended to help them

2) Equitable: Doesn’t vary because of personal characteristics

3) Patient-centered: Is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs and values

4) Timely: Reduces waits and potentially harmful delays

5) Efficient: Avoids waste of equipment, supplies, ideas and energy

6) Effective: Services are based on scientific knowledge to all who could benefit, and it accomplishes what it sets out to accomplish

In 1994, I moved to New Hampshire and obtained a Master’s Degree in “Evaluative Clinical Sciences” to learn how to measure, and hopefully improve, medical quality. I had been working around this for years, serving on the Medicare Peer Review Organization for California and serving in several positions in organized medicine.

I spent a few years trying to work with the system, with a medical school for example, and finally gave up. A friend of mine had set up a medical group for managed care called CAPPCare, which was to be a Preferred Provider Organization when California set up “managed care.” It is now a meaningless hospital adjunct. In 1995, he told me, “Mike you are two years too early. Nobody cares about quality.” Two years later, we had lunch again and he laughed and said “You are still too years too early.”

The Energy Crisis in Africa.

This is a powerful piece on the cost of environmental extremism to the world’s poor.

The soaring [food] prices were actually exacerbated (as the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the UN confirmed) by the diversion of much of the world’s farmland into making motor fuel, in the form of ethanol and biodiesel, for the rich to salve their green consciences. Climate policies were probably a greater contributor to the Arab Spring than climate change itself.

The use of ethanol in motor fuels is an irrational response to “green propaganda. The energy density of biofuel, as ethanol additives are called, is low resulting in the use of more and more ethanol and less and less arable land for food.

Without abundant fuel and power, prosperity is impossible: workers cannot amplify their productivity, doctors cannot preserve vaccines, students cannot learn after dark, goods cannot get to market. Nearly 700 million Africans rely mainly on wood or dung to cook and heat with, and 600 million have no access to electric light. Britain with 60 million people has nearly as much electricity-generating capacity as the whole of sub-Saharan Africa, minus South Africa, with 800 million.

South Africa is quickly destroying its electricity potential with idiotic racist policies.

Just to get sub-Saharan electricity consumption up to the levels of South Africa or Bulgaria would mean adding about 1,000 gigawatts of capacity, the installation of which would cost at least £1 trillion. Yet the greens want Africans to hold back on the cheapest form of power: fossil fuels. In 2013 Ed Davey, the energy secretary, announced that British taxpayers will no longer fund coal-fired power stations in developing countries, and that he would put pressure on development banks to ensure that their funding policies rule out coal. (I declare a commercial interest in coal in Northumberland.)

In the same year the US passed a bill prohibiting the Overseas Private Investment Corporation — a federal agency responsible for underwriting American companies that invest in developing countries — from investing in energy projects that involve fossil fuels.

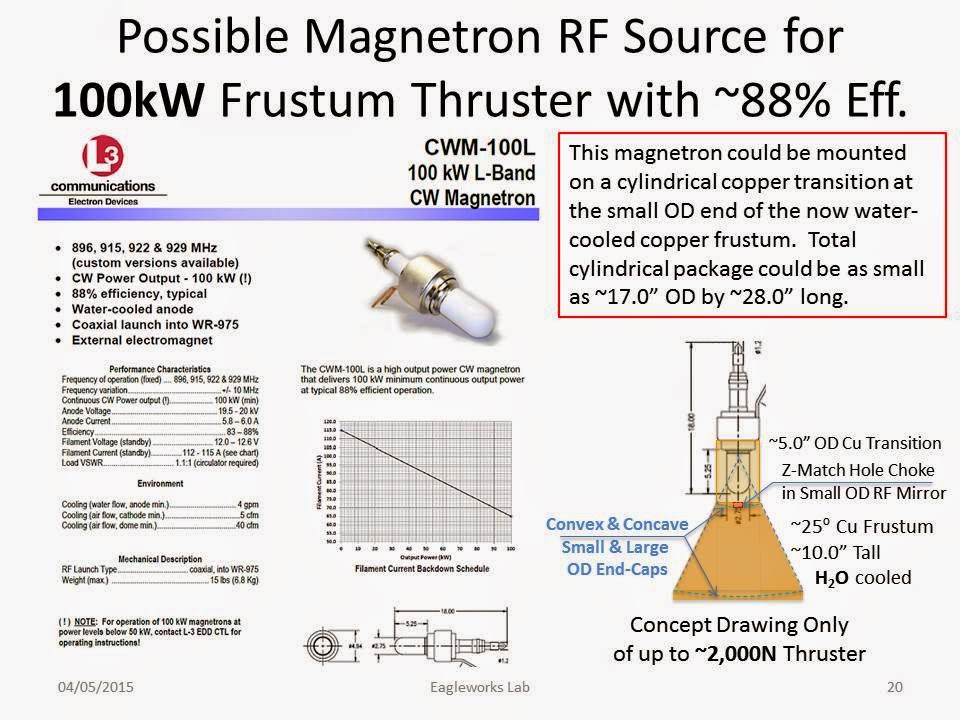

Shawyer Space Drive…Arriving.

A science fiction writer acquaintance of mine, John Ringo, is already going nuts about this “Shawyer Drive” on his Facebook page, because he

is friends with one of the scientists involved.

See power point page and the links below:

Magnetron powered EM-drive construction expected to take two months

http://nextbigfuture.com/2015/04/magnetron-powered-em-drive-construction.html

Emdrive Roger Shawyer believes midterm EMdrive interstellar probe could flyby Alpha Centauri

http://nextbigfuture.com/2015/04/emdrive-roger-shawyer-believes-midterm.html

The drive seems to be a quantum “zero-point energy” phenomena that you put electricity into and get reaction massless thrust out of.

_AND_ it looks to be both scalable and improvable with better magnetrons.

This is also dovetailing nicely with a Lockheed Martin compact fusion reactor that

1. Generates more power than it uses and

2. Produces something on the order of 7.4 megawatts

See:

http://www.lockheedmartin.com/us/products/compact-fusion.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High_beta_fusion_reactor

Given the reality of Space X’s and Blue Origin’s reusable rocket successes, and it seems that Mankind is about to burst out from this planet in a very big way.

See:

http://www.spacex.com/news

http://www.wired.com/2015/04/jeff-bezos-blue-origin-just-launched-flagship-rocket/

And all of the above is driving John Ringo to despair on his science fiction writing career.

Myopia and why it is increasing.

A couple of interesting articles about the increasing incidence of myopia in children.

Myopia isn’t an infectious disease, but it has reached nearly epidemic proportions in parts of Asia. In Taiwan, for example, the percentage of 7-year-old children suffering from nearsightedness increased from 5.8 percent in 1983 to 21 percent in 2000. An incredible 81 percent of Taiwanese 15-year-olds are myopic.

The first thought is that this is an Asian genetic thing. It isn’t.

In 2008 orthoptics professor Kathryn Rose found that only 3.3 percent of 6- and 7-year-olds of Chinese descent living in Sydney, Australia, suffered myopia, compared with 29.1 percent of those living in Singapore. The usual suspects, reading and time in front of an electronic screen, couldn’t account for the discrepancy. The Australian cohort read a few more books and spent slightly more time in front of the computer, but the Singaporean children watched a little more television. On the whole, the differences were small and probably canceled each other out. The most glaring difference between the groups was that the Australian kids spent 13.75 hours per week outdoors compared with a rather sad 3.05 hours for the children in Singapore.

This week the Wall Street Journal had more. There are some attempts to deal with the natural light effect.

Children in this small southern Chinese city sit and recite their vocabulary words in an experimental cube of a classroom built with translucent walls and ceilings. Sunlight lights up the room from all directions.

The goal of this unusual learning space: to test whether natural, bright light can help prevent nearsightedness, a problem for growing numbers of children, especially in Asia.

The schools have tried to get Chinese parents to send the kids outdoors more but it doesn’t seem to work.

And it isn’t limited to Asians.

In the U.S., the rate of nearsightedness in people 12 to 54 years old increased by nearly two-thirds between studies nearly three decades apart ending in 2004, to an estimated 41.6%, according to a National Eye Institute study.

But Asians with their focus on education are the most effected.

A full 80% of 4,798 Beijing teenagers tested as nearsighted in a study published in the journal PLOS One in March. Similar numbers plague teens in Singapore and Taiwan. In one 2012 survey in Seoul, nearly all of the 24,000 teenage males surveyed were nearsighted.

So, what to do ?

Though glasses can correct vision in most myopic children, many aren’t getting them. Sometimes this is because parents don’t know their children need glasses or don’t understand how important they are for education. Other times, cultural beliefs lead parents to discourage their children from wearing them, according to Nathan Congdon, professor at Queen’s University Belfast and senior adviser to Orbis International, a nonprofit focused on preventing blindness. Many parents believe glasses weaken the eyes—they don’t.

Getting kids to spend even small amounts of time outdoors makes a difference.

Why myopia rates have soared isn’t entirely clear, but one factor that keeps cropping up in research is how much time children spend outdoors. The longer they’re outside, the less likely they are to become nearsighted, according to more than a dozen studies in various countries world-wide.

One preliminary study of 2,000 children under review for publication showed a 23% reduction in myopia in the group of Chinese children who spent an additional 40 minutes more outside each day, according to Ian Morgan, one of the researchers involved in the study and a retired professor at Australian National University in Canberra. (He still conducts research with Sun Yat-sen University in the Chinese city of Guangzhou.)

That is a very significant effect of small changes in behavior. Now the researchers are trying something new.

Dr. Morgan, Dr. Congdon and a team from Sun Yat-sen are now testing, as reported recently in the science magazine Nature, a so-called bright-light classroom made of translucent plastic walls in Yangjiang to see if the children can focus and sit comfortably in the classroom. So far it appears the answer is yes.

In 2007, Donald Mutti and his colleagues at the Ohio State University College of Optometry in Columbus reported the results of a study that tracked more than 500 eight- and nine-year-olds in California who started out with healthy vision6. The team examined how the children spent their days, and “sort of as an afterthought at the time, we asked about sports and outdoorsy stuff”, says Mutti.

It was a good thing they did. After five years, one in five of the children had developed myopia, and the only environmental factor that was strongly associated with risk was time spent outdoors6. “We thought it was an odd finding,” recalls Mutti, “but it just kept coming up as we did the analyses.” A year later, Rose and her colleagues arrived at much the same conclusion in Australia7. After studying more than 4,000 children at Sydney primary and secondary schools for three years, they found that children who spent less time outside were at greater risk of developing myopia.

What is the mechanism ? Maybe it is this.

The leading hypothesis is that light stimulates the release of dopamine in the retina, and this neurotransmitter in turn blocks the elongation of the eye during development. The best evidence for the ‘lightdopamine’ hypothesis comes — again — from chicks. In 2010, Ashby and Schaeffel showed that injecting a dopamine-inhibiting drug called spiperone into chicks’ eyes could abolish the protective effect of bright light11.

Retinal dopamine is normally produced on a diurnal cycle — ramping up during the day — and it tells the eye to switch from rod-based, nighttime vision to cone-based, daytime vision. Researchers now suspect that under dim (typically indoor) lighting, the cycle is disrupted, with consequences for eye growth. “If our system does not get a strong enough diurnal rhythm, things go out of control,” says Ashby, who is now at the University of Canberra. “The system starts to get a bit noisy and noisy means that it just grows in its own irregular fashion.”

Another possible treatment is the use of atropine drops in the eye.

Atropine, a drug used for decades to dilate the pupils, appears to slow the progression of myopia once it has started, according to several randomized, controlled trials. But used daily at the typical concentration of 1%, there are side effects, most notably sensitivity to light, as well as difficulty focusing on up-close images.

In recent years, studies in Singapore and Taiwan found that a lower dose of atropine reduces myopia progression by 50% to 60% in children without those side effects, says Donald Tan, professor of ophthalmology at the Singapore National Eye Centre. He has spearheaded many of the studies. Large-scale trials on low-dose atropine are expected to start soon in Japan and in Europe, he says.

More than a century ago, Henry Edward Juler, a renowned British eye surgeon, offered similar advice. In 1904, he wrote in A Handbook of Ophthalmic Science and Practice that when “the myopia had become stationary, change of air — a sea voyage if possible — should be prescribed”.