Over at Trust Funds for Kids I commented on some recent stock moves and the rally in China…

Month: May 2015

The Energy Crisis in Africa.

This is a powerful piece on the cost of environmental extremism to the world’s poor.

The soaring [food] prices were actually exacerbated (as the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the UN confirmed) by the diversion of much of the world’s farmland into making motor fuel, in the form of ethanol and biodiesel, for the rich to salve their green consciences. Climate policies were probably a greater contributor to the Arab Spring than climate change itself.

The use of ethanol in motor fuels is an irrational response to “green propaganda. The energy density of biofuel, as ethanol additives are called, is low resulting in the use of more and more ethanol and less and less arable land for food.

Without abundant fuel and power, prosperity is impossible: workers cannot amplify their productivity, doctors cannot preserve vaccines, students cannot learn after dark, goods cannot get to market. Nearly 700 million Africans rely mainly on wood or dung to cook and heat with, and 600 million have no access to electric light. Britain with 60 million people has nearly as much electricity-generating capacity as the whole of sub-Saharan Africa, minus South Africa, with 800 million.

South Africa is quickly destroying its electricity potential with idiotic racist policies.

Just to get sub-Saharan electricity consumption up to the levels of South Africa or Bulgaria would mean adding about 1,000 gigawatts of capacity, the installation of which would cost at least £1 trillion. Yet the greens want Africans to hold back on the cheapest form of power: fossil fuels. In 2013 Ed Davey, the energy secretary, announced that British taxpayers will no longer fund coal-fired power stations in developing countries, and that he would put pressure on development banks to ensure that their funding policies rule out coal. (I declare a commercial interest in coal in Northumberland.)

In the same year the US passed a bill prohibiting the Overseas Private Investment Corporation — a federal agency responsible for underwriting American companies that invest in developing countries — from investing in energy projects that involve fossil fuels.

Introducing: Asabiyah

This post was originally published at The Scholar’s Stage on 2 May 2015. It has been re-posted here without alteration.

If mankind is, as has been claimed since ancient days, a species driven by the narrow passions of self interest, what holds human society together as one cohesive whole? How can a community of egoists, each devoted to nothing but his or her own ambition, thrive? Or for that matter, long exist?

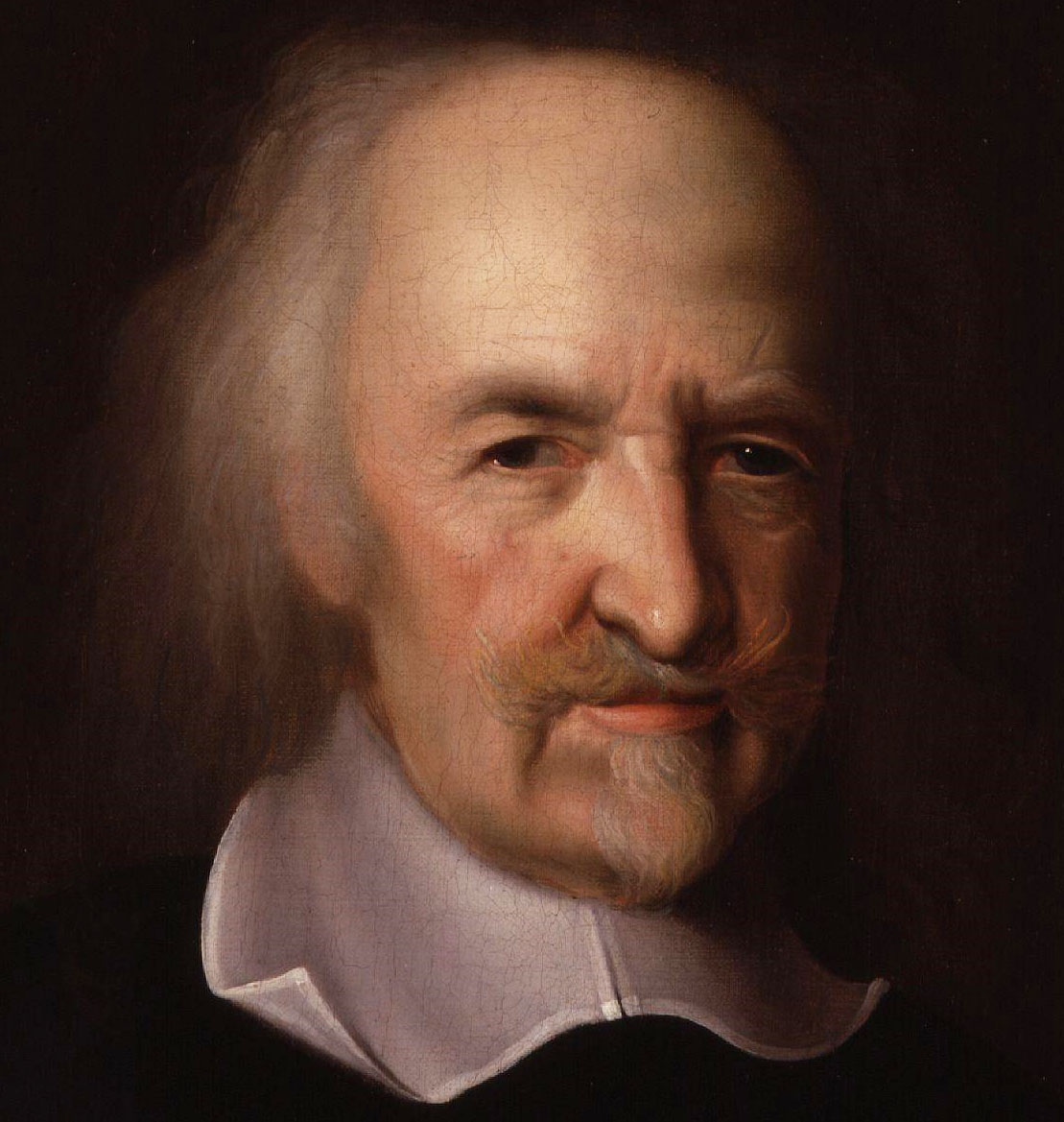

Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury thought he knew the answer.

|

| John Michael Wright, Thomas Hobbes (17th c). Image Source. |

Hobbes is famous for his dismal view of human nature. But contrary to the way he is often portrayed, Hobbes did not think man was an inherently evil being, defiled by sin or defined by vileness ingrained in his nature. He preferred instead to dispense with all ideas of good and evil altogether, claiming “these words of good, evil, and contemptible, are ever used with relation to the person that useth them, there being nothing simply and absolutely so; nor any common rule of good and evil, to be taken from the nature of the objects themselves; but from the person of the man.” [1] Only a superior power, “an arbitrator of judge, whom men disagreeing shall by consent set up” might have the coercive force to make one meaning of right the meaning used by all. Absent such a “common power”, the world is left in a condition that Hobbes famously described as “war of every man against every man” where they can be no right, no law, no justice, and “no propriety, no dominion, no ‘mine’ and ‘thine’ distinct, but only that to be every man’s that he can get, and for so long as he can keep it.” [2]

This description of the wretched State of Nature is familiar to most who have studied in the human sciences at any length. Also well known is Hobbes’s solution to the challenge posed by anarchy:

[Those in this state will] appoint one man, or assembly of men, to bear their person; and every one to own and acknowledge himself to be author of whatsoever he that so beareth their person shall act, or cause to be acted, in those things which concern the common peace and safety; and therein to submit their wills, every one to his will, and their judgements to his judgement. This is more than consent, or concord; it is a real unity of them all in one and the same person, made by covenant of every man with every man, in such manner as if every man should say to every man: I authorise and give up my right of governing myself to this man, or to this assembly of men, on this condition; that thou give up, thy right to him, and authorise all his actions in like manner. This done, the multitude so united in one person is called a COMMONWEALTH; in Latin, CIVITAS. [3]

What is most striking in Hobbes’ vision of this State of Nature and the path by which humanity escapes it is his complete dismissal of any form of cooperation before sovereign authority is established. Neither love nor religious zeal holds sway in the world Hobbes describes, and he has no more use for ties of blood or oaths of brotherhood than he does for the words right and wrong. He does concede that if faced with large enough of an outside threat fear may drive many “small families” to band together in one body for defense. However, the solidarity created by an attack or invasion is ephemeral–once the threat fades away so will the peace. “When there is no common enemy, they make war upon each other for their particular interests” just as before. [4] Hobbes allows for either a society dominated by a sovereign state or for a loose collection of isolated individuals pursuing private aims.

Hobbes’ dichotomy is not presented merely as a thought experiment, but as a description of how human society actually works. Herein lies Hobbes’ greatest fault. Today we know a great deal about the inner workings of non-state societies, and they are not as Hobbes described them. The man without a state is not a man without a place; he is almost always part of a village, a tribe, a band, or a large extended family. He has friends, compatriots, and fellows that he trusts and is willing to sacrifice for. His behavior is constrained by the customs and mores of his community; he shares with this community ideas of right and wrong and is often bound quite strictly by the oaths he makes. He does cooperate with others. When he and his fellows have been mobilized in great enough numbers their strength has often shattered the more civilized societies arrayed before them.

The social contract of Hobbes’ imagination was premised on a flawed State of Nature. The truth is that there never has been a time when men and women lived without ties of kin and community to guide their deeds and restrain their excess, and thus there never could be a time when atomized individuals gathered together to surrender their liberty to a sovereign power. Hobbes mistake is understandable; both he and the social contract theorists that followed in his footsteps (as well as the Chinese philosophers who proposed something close to a state of nature several thousand years earlier) lived in an age where Leviathan was not only ascendent but long established. They were centuries removed from societies that thrived and conquered without a state. [5]

To answer the riddle of how individuals “continually in competition for honour and dignity” could form cohesive communities without a “a visible power to keep them in awe, and tie them by fear of punishment to the performance of their covenants,” [6] or why such communities might eventually create a “common power” nonetheless, we must turn to those observers of mankind more familiar with lives spent outside the confines of the state. Many worthies have attempted to address this question since Hobbes’ say, but there is only one observer of human affairs who can claim to have solved the matter before Hobbes ever put pen to paper. Centuries before Hobbes’s birth he scribbled away, explaining to all who would hear that there was one aspect of humanity that explained not only how barbarians could live proudly without commonwealth and the origin of the kingly authority that ruled civilized climes, but also the rise and fall of peoples, kingdoms, and entire civilizations across the entirety of human history. He would call this asabiyah.

Baltimore’s Lose-Lose choice

Now that charges have been brought against the 6 officers involved Baltimore’s streets will return to their state of a month ago. But there will be a trial and that trial will have a significant impact on the direction of Baltimore’s future. The trial has three possible outcomes:

First, the trial can be seen by most to have been fair and just.

Second, the trial results in acquittals seen to be unjust by the city black community.

Third, the trial can result in convictions seen outside Baltimore as unjust.

The first seems least likely based on Ms Mosby’s performance announcing the charges on May Day. But in the event the prosecution and trial are depoliticized Baltimore could resume its leisurely contraction into a bedroom community for Washington D. C.

But if either the second or third options eventuate they could turn Baltimore into a much different place. Acquittals would reignite rioting on the scale of 1968. A kangaroo court would indicate that the rule of law had degenerated into tribal justice. In either event, the abandonment of Baltimore by private employers and what’s left of its middle class would accelerate.

Headquarters are important to a community. They provide the leaders who are committed to the health of the community. When the head of every organization has eyes on promotion to a bigger job closer to headquarters there is not the continuity or commitment necessary to make the long term investments to support the young and less fortunate in the community. Today of the 25 largest employers headquartered in Baltimore only three are not education, government or healthcare related; T. Rowe Price, the mutual fund company, and Broadway Services and Abacus, security guard and janitorial contracting firms. Johns Hopkins won’t be able to do it alone.

This lack of headquarters also indicates that there is little economic reason for Baltimore to exist. The primary force in Baltimore is inertia leading to ever greater entropy. All solutions are temporary and Baltimore no longer solves a problem.

So, if Baltimore’s judicial environment begins to look more and more like Dodge City circa 1880 and it has little economic opportunity, who will stay? Disinvestment and declining tax base will result in inadequate funds to provide even minimal services to an increasingly needy and unassimilated population. Financial support will increasingly come from sources other than the city itself, primarily the Federal government. Sounds like an Indian reservation to me. And Baltimore will not be alone in this transition, only first.

When I lived there the local brew, Natty Boh, advertised to its market as the Land of Pleasant Living. Now it ain’t even got charm, hon.

New! – Your Overcaffeinated Reality-Based Haiku Extravaganza

How to disconnect?

“Windows can’t stop your volume”

Just turn the thing off

—-

“TSA Pre-Check”

It’s like receiving a gift

That leaves your shoes on

—-

On TV shows now

It’s easy to spot the tropes

From Manosphere blogs

—-

Midget urinals,

Terrible low-flow toilets –

Can’t we do better?