Today’s History Friday column is another in a series focusing on an almost unknown series of military documents from World War II (WW2) called “The Reports of the Pacific Warfare Board,” and specifically Pacific Warfare Board (PWB) Report #35 Armor Vest, T62E1 and Armor Vest T64. (See photo below) This report, like most of the PWB reports, had been classified for decades and only now thanks to the cratering costs USB flash drives and increasing quality of digital cameras has it become possible for the interested hobbyist or blogger to access and write about these reports from the formally hard to use National Archives. And PWB #35 is about one of those hugely important but overlooked details — Infantry Body Armor — that utterly undermine the established historical narratives by the professional Military history community about the end of WW2 in the Pacific. Namely that the Japanese would so bloody attacking American invasion forces the Japanese would “win” for values of winning a more favorable settlement of the war.

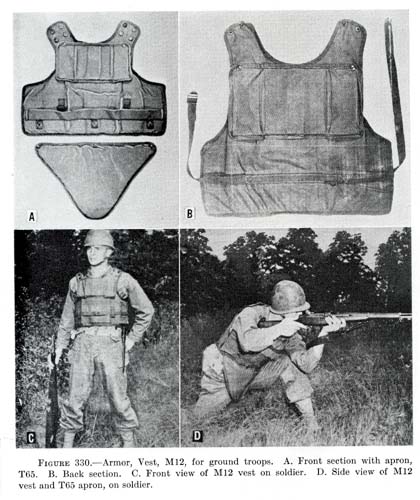

According to PWB #35, both the T62E1 and T64 vest (the latter is pictured above and was standardized as the M12 in August 1945) were sent for combat testing to MacArthur’s 6th and 8th Army’s in the Philippines in June and July 1945. The T64 vest was chosen for series production as the M12 in the summer of 1945 with 100,000 supposed to be finished by the end of August. This was sufficient time to ship those vest to the Pacific for all the assault infantry regiments participating the cancelled by A-bomb invasion of Japan, code named Operation Olympic.

Why infantry body armor like the M12 is so disruptive for the established narratives boils down to one word — casualties. The deployment of 100,000 such vests would have reduced American infantry casualty rates from lethal artillery fragments in the invasion of Japan to roughly Vietnam levels. This means roughly 1/3 fewer combat deaths from artillery fragments and about an overall 10% to 20% reduction in total projected combat deaths. Depending on which of the historical casualty ratios you select for measurement, it means something on the order of up to 10,000 fewer battle deaths, in the event that the A-bomb hadn’t made the invasion superfluous.

I would call this a very significant, reality altering, detail.

INTERNET DETAIL

When you do internet searches on this T64/M12 body armor, there is a wealth of detail on line, with the two biggest hits are Osprey Publishing’s “Flak Jackets – 20th-century military body armour,” by Simon Dunstan and the on-line version of WOUND BALLISTICS, by the US Army Medical Department’s Office of Medical History. The former used much of the latter verbatim, so I will take WOUND BALLISTICS as definitive. The following is from page 737, the on-line chapter 12, of WOUND BALLISTICS regards the effectiveness of the Korean War vest T-51-2 (also pictured below):

“These studies indicate that 30 to 40 percent of the fatal chest wounds incurred by soldiers in combat would have been prevented by the use of body armor. From another point of view, this seems to indicate that 10 to 20 percent of the soldiers who were killed in action would have survived if they had worn body armor. The effectiveness of the vest in preventing chest wounds in the KIA casualties was not so marked as in the WIA casualties. One explanation of this disparity lies in the higher incidence of small arms wounds in the KIA (approximately 25 percent) as compared to the WIA casualties (approximately 15 percent).

Pictured below are the various artillery and bullet fragments picked out of the six pound Korean War vest T-51-2

Too make things even more interesting, the same internet search that found the above information also found a hobbyist the US Militaria forum has actually built a simulation of the M12 vest and fired ammo at it. His results suggest that a 12 pound M12 vest might have been rated as high as “Level IIIA” in some places (stops most moderately powered pistol rounds). See the link:

http://www.usmilitariaforum.com/forums/index.php?/topic/200707-the-t64-armor-vest-may-have-been-as-high-as-level-3a/

CRUNCHING THE IWO JIMA NUMBERS

To baseline what the difference the M12 vest would have made for the invasion of Japan, I pulled a pair of military medical reports on Iwo Jima — one a March 1945 US Army report and one post war US Navy (See notes) — to crunch numbers. The USMC Assault infantry regiments suffered 75% casualties of initial strength over the course of the Iwo Jima battle. The supporting regiments took 60% casualties.

What is interesting here is that in terms of “Casualties per thousand per day,” the military-medical standard measurement of casualties. Iwo Jima was much less bloody in terms of casualties per 1000 per day than Tarawa, at 12.74 versus Tarawa’s 80.55 per 1000. And more surprising still, the USMC assault with the highest casualty rate for the first day was Saipan, at 100 casualties per 1000.

The difference between either Tarawa or Saipan and Iwo Jima was time. Tarawa was three days long. The assault on Iwo Jima was 26 days.

In terms of battle deaths on Iwo Jima, there were 5,460 dead, 22% whom died of wounds after getting to medical treatment. Had the M12 been available to the Iwo Jima Marines, we are looking at 546 to 1092 more Marines surviving the battle, using the Korea war data for a less well armored T-51-2 vest…and the M12 vest was much more protective!

Now you all have a better idea why I think the arrival of the digital age is undermining past historical narratives.

Notes and Sources —

1. Major JAMES C. BEYER, MC, ed. “MEDICAL DEPARTMENT, UNITED STATES ARMY, WOUND BALLISTICS” OFFICE OF THE SURGEON GENERAL DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY WASHINGTON, D.C., 1962

o CHAPTER XI Personnel Protective Armor

http://history.amedd.army.mil/booksdocs/wwii/woundblstcs/chapter11.htm

o Chapter XII Wound Ballistics and Body Armor in Korea

http://history.amedd.army.mil/booksdocs/wwii/woundblstcs/chapter12.htm

2. C.G. Blood, Report No. 90-16, “SHIPBOARD AND GROUND TROOP CASUALTY RATES AMONG NAVY AND MARINE CORPS PERSONNEL DURING WORLD WAR II OPERATIONS,” Naval Health Research Center, Medical Decisions Support Department, P.O. Box 85122, San Diego, CA 92186-5122

3. Simon Dunstan, Men-at-Arms 157, “Flak Jackets – 20th-century military body armour,” Osprey Publishing, June 1984; ISBN: 9780850455694

http://www.ospreypublishing.com/store/Flak-Jackets_9780850455694

4. Captains Charles F. Koser and Daniel Prettyman, US Army Medical Corps, “The Iwo Jima Operation (19 February to 16 March 1945),” March 1945, N-18600.1-E, CGSC Ft. Leavenworth, Kan. DTIC Accession Number ADB308635 Page 4

5. Pacific Warfare Board Report #35, NARA

A very special thanks here for Ryan Crierie of the AlternateWars.com web site for assistance in this article.

Very interesting. Any thoughts on the trade-off in ammo/equipment carried, or loss of mobility/endurance of the soldiers?

The treatment of battle casualties rapidly improved. For one example, there was no successful repair of an artery in WWII. In Vietnam they were routine. I don’t recall the number for Korea. The helicopter was the next biggest influence. Wounded soldiers in Vietnam, who got to the first medical unit alive, had about a 95% survival. In WWII the delay from wound to initial care was in hours. I’ve forgotten the numbers but it was about 12 in WWII. In Vietnam it was around an hour on average. I have some of the numbers in my book. The US Civil War was not the first to use anesthesia, the Crimean was. The Franco-Prussian War in 1870 was the first after antisepsis but the French still had a 70% mortality from amputations. The Prussians had much better wound care even though the whole military medicine field was invented by Baron Larrey, Napoleon’s surgeon. Billroth studied the book written on the US Civil War and adopted most of its findings.

Vietnam did have one medical error in treatment that became known as “Da Nang Lung” and was from using too much saline solution instead of blood or plasma.

There were no artillery shrapnel wounds in the Civil War although General Shrapnel, who invented it (as a lieutenant) had done so years before the war. All the wounds were rifle bullet wounds except for the occasional cannon ball. The Minie’ Ball , which was invented by Captain Minie’, made rifle fire much more deadly with the introduction of the rifled musket. It was an order of magnitude more effective than the smoothbore musket and the effect was similar to that of the machine gun in WWI.

Re your photos – there’s a rare MOS – “model”

Dr. K, as much as I am loathe to disagree with you, Civil War artillery on both sides very rarely used solid shot. Almost all rounds that were not canister [like giant shotgun shells] were what were called spherical case shot. And those were explosive rounds with time fuses designed to explode in the air near troops and over entrenchments. The Brits called them Shrapnel after the inventor, we called them spherical case shot. Below is a link to a picture of an intact Civil War era round minus the bag of propellant powder that was attached to the wooden “shoe” at the base with cord.

http://tinyurl.com/m5esgys

Originally, the projection at the top was where the rolled, chemically treated, paper fuse was inserted. Later, instead of paper, a mechanically set Bormann fuse was placed there. The gunner, after sighting through the pendulum-hausse, would call back to the ammunition limber how he wanted the fuse cut or set to determine the delay before the round exploded in the air. The fused round, which was a unitary round manufactured with the powder bag, shoe, and bands holding the actual shot, was brought up and loaded from the muzzle. At the firing, the flame from the propellant would light the fuse which would burn in flight until detonation.

Here is a cutaway of that type of shot:

http://tinyurl.com/oos8r3w

Note the cylinder of explosive powder below the fuse fitting, the lead balls imbedded in a resin matrix, and of course the cast iron hollow projectile. The projectile would shatter into what we would call shrapnel and with the lead balls devastate any troops in the area of the explosion.

Although it has been a while ago, I was active in living history reenacting at Bent’s Fort, and at presentations for schools; both as a US Dragoon artilleryman [12-lb. Mountain Howitzer] for the period 1833-1859 [when they became Cavalry] and Civil War Infantry and Artillery. Spherical case shot was issued to US forces in the Dragoon era. In the Civil War mode, I crewed both 12-lb. Mountain Howitzer and a restored, authentic period Union 3″ Ordnance Rifle. The Ordnance Rifle had a cylindrical, rifled, version of case shot.

I base my statements on being a qualified gunner to be both chief of a piece and to train crews. I myself was trained by Virgil Hughes who was the technical director of the artillery for the movie “Gettysburg”. I have also played “1st Chair 12-lb. Mountain Howitzer” with the Colorado Symphony Orchestra several times for the 1812 Overture.

>>Any thoughts on the trade-off in ammo/equipment carried,

>>or loss of mobility/endurance of the soldiers?

Gen Krueger and Adm Turner in the Pacific were absolute pro’s in a way that Ike and Bradley were not. Notably they were better at beach intelligence.

The inability to _see_ the true firepower of the German beach defenses meant Bradley’s plan placed his troops into the draws of Omaha Beach ”” the kill zones ”” expecting weak defenses, having outfitted his men to carry a basic load for two-to-three days fighting inland when they needed a minimum combat load.

What chapter 11 of WOUND BALLISTICS (see notes and sources link) mentions in passing was that Ike and Bradley were offered an earlier form of body armor and turned it down because it would cut into that overload.

Go re-read by D-Day book review column “History Friday ”” Books to Read for the D-Day 70th Anniversary” and consider the “For want of a nail, the kingdom was lost” implications and incentives of that decision.

Had the body armor been used at the price of that 2-to-3 day load Bradley’s planners had proscribed, roughly 10% on the men pinned down the first five hours on Omaha Beach would have lived.

The use of body armor would have rapidly spread in the American and later the Allied armies after that and saved thousands of lives around the world.

But instead, after Bloody Omaha, there has a huge incentive by those involved in planning Omaha NOT TO give body armor a “combat test” least there be serious questioning of the planning going into the D-Day landings at Normandy.

It wasn’t until the war in Europe was over that MacArthur got Body Armor to Combat test.

The US Marines got body armor for Okinawa before MacArthur, but they were with the reserve Marine Regiments in the reserve Marine division and never reached combat.

It may well be that canister shot caused many wounds but I could not find a description of what we would call “Shrapnel” wounds in the history.

Total deaths 304,369

Regular Army- 5,724

Volunteers- 265,265

Colored Troops- 33,380

Killed in Battle- 44,238

Died of Wounds- 49,205

Died of Disease- 186,216

Colored 29,212 90% of deaths in colored troops

Other causes- 526

Suicide- 302

Homicide- 103

Execution 121

Unknown Causes- 24,184

Troops discharged alive as disabled- 285,545

Those are Union Army deaths. I have read the History, which is 12 volumes and which is the definitive history of the medical care of the army. I can’t find a description of the sort of wounds these days described as from artillery. In World War II, the vast majority of wounds was from artillery and mortars.

From the US Military history of care of wounds.

Although in all wars before World War II various antipersonnel loads such as canister, grapeshot, chain shot, and shrapnel were used, experience had conclusively demonstrated the comparative ineffectiveness of these agents for antipersonnel purposes. The HE projectile, however, had proved to be not only more effective in producing casualties but had also proved capable at the same time of inflicting materiel damage which is often of greater importance in carrying out the artillery mission.

I should have included canister as a mechanism of wounding but shrapnel and explosive shells do not seem to have been a major cause of wounding. There are, for example, several depictions of saber wounds from cavalry. No descriptions of the sort of tearing wounds seen from shrapnel are included. It may be that most exploding shot were used against structures, rather than as air bursts.

Dr. K:

For the moment, I think we will have to agree to disagree. I cannot come up with a documentary source on short notice. However, I think part of the problem is a matter of what is documented. I will note a few specific examples:

http://i.livescience.com/images/i/000/015/948/i02/cranium-fracture.jpg?1302552958

Credit: Otis Historical Archives Nat’l Museum of Health & Medicine

A confederate soldier killed by shell July 12, 1864. Physician: Dr. Henry Dean.

http://i.livescience.com/images/i/000/015/946/i02/williams-civil-war.jpg?1302551364

Credit: Otis Historical Archives Nat’l Museum of Health & Medicine

Hiram Williams had his leg and foot amputated due to a shell wound in the Battle of Appomattox in 1865.

http://www.livescience.com/images/i/000/015/945/i02/gangrene-wrist.jpg?1302549988

Credit: Otis Historical Archives Nat’l Museum of Health & Medicine

A shell wound of the left wrist, with signs of gangrene. Photo was taken on Aug. 10, 1864.

These are listed as “shell” wounds. Shells were either common shell, which were hollow rounds filled with gunpowder and a time fuse, or case shot, which were slightly thinner cased time fused hollow rounds with the balls as described in my previous post. Both exploded after the time fuse burned. The effect was fragments of the round [and balls from case shot] flying into enemy soldiers like the Brit Shrapnel rounds.

YMMV

As I said, we can agree to disagree.

Best regards,

Subotai Bahadur

“As I said, we can agree to disagree.”

I just can’t find much evidence of shrapnel-like wounds. Could it be that the Union had more explosive shells than the Confederacy ? Maybe there was a difference. The History is mostly about Union army wounds.

I am convinced that the Union army’s decision to not use repeating rifles prolonged the war and radically increased casualties. Several units bought Henry repeating rifles with private funds and used them with devastating results. The Confederacy scavenged a lot of Union muskets from the battlefield. They did not have the industry to manufacture brass cartridges for the Henry rifle. The story is here .

The men of the 7th Illinois Veteran Volunteer Infantry, the 66th WSS and many others that purchased their own Henry Rifles did indeed make a conscience choice of putting up $35 to $50 of their own money for a weapon that they felt would give them an advantage and improve their chances of survival in the war.

Why they didn’t buy it.

In a letter dated December 9, 1861 from General Ripley he writes to Simon Cameron the Secretary of War letting him know that he is not in favor of a repeating rifle. He writes, “Sir: As directed from the War Department, I have examined the reports upon the Henry and Spencer guns accompanying the proposition to furnish these arms to the Government and have also examined the arms. Both of them are magazine arms; that is to say, they have the cartridges for use carried in a magazine attached to or forming part of the arm and fed out by a spiral spring. They require a special kind of ammunition, which must be primed or have the fulminate in itself.

Dr. K:

Agreed on the repeating rifles. It was a continuing problem with the War Department, not wanting to go to the expense of a better weapon. Going back to the US Dragoons, they were armed with the Model 1836 Hall’s Carbine. A breachloading caplock, the first ever issued to a military force anywhere in the world.

Rather than continue buy percussion caps, the War Department later downgraded them to the Springfield Model 1847 Musketoon of which the Army Inspector General stated in 1853 that the gun was essentially “a worthless arm,” having “no advocates that I am aware of.”. However, as a flintlock it did not require caps, and the War Department said that the Dragoons could always find flint to make into flints while stationed in the West.

Also, the South did use explosive rounds, keeping in mind that Confederate military leaders mostly used to be US military. Their quality control, as shown by archeological examination of the fragments found on battlefields, was worse; but they used the same doctrine for both cavalry and artillery. I have their period official training manuals in reprint [and one of their cavalry manuals in an actual early war edition].

Subotai Bahadur

Dr. K., Henry Shrapnel actually called his innovation “spherical case shot”. In British use, it came to be known by its inventor’s name. In U.S. use, we kept the original nomenclature. The Civil War Artillery site has pictures of the many different types of ammunition in use. In field battles, not much solid shot was used compared to other types. Solid shot was mostly used at long range, or against structures. It wasn’t terribly effective, but since they had long range and would bounce and roll through the rear areas, it could cause some casualties and disruptions in reserve units. Case shot would be used against infantry until much shorter-ranged canister would be useful.

I doubt whether any accurate statistics would’ve been kept over causes of death when it might’ve been a ball from canister or case shot or a Minie ball from a rifle. No autopsies would’ve been done. In many treated wounds, I doubt you’d have been able to tell which kind of ball caused it (for pass-though wounds, for example, or in some cases if it hit bone). In the various sieges, very large explosive shells were fired. Mortars almost exclusively fired explosive shells. Dud rounds are still occasionally found around old battlefields, and can still be deadly. A collector was killed just a years ago drilling out one he’d found, in order to render it safe. He’d done so before without a problem, but that one got him.

I should have included canister as a source of wounds but there is little or no mention of wounds typical of the steel fragments from case shot. The History was used for many years as the definitive source for military medicine. World War I changed things with blood transfusion and knowledge of infection. Blood transfusion was actually introduced by the Americans in 1917 and saved many lives. One huge problem in WWI was tetanus but it was not seen in the Civil War as horse manure was not used as fertilizer in the South where almost all battles were fought. Tetanus antitoxin appeared quickly after 1914 but it was major problem early in Belgium where horse manure was universal as fertilizer.

The British were quite backward medically compared to the Germans until late WWI. The major source of death in the Boer War was typhoid, not wounds, for example.

The vast majority of the wounds caused by case shot (called ‘shrapnel’ by the British) would have been from the balls contained within, not from the fragments of the relatively thin casings. The entire point of its invention was that fragments of the shells produced with the metallurgy and industrial techniques of the time were inefficient wound generators. I don’t understand how one could determine what the source of the wounding ball was with the forensics of the time unless 1) the ball used in each type of ammunition was sufficiently unique, 2) that such detailed information was available (I have my doubts about that), and 3) were sufficiently undamaged on impact to identify (being soft lead, I wouldn’t be surprised if a large percentage were unidentifiable).

” that such detailed information was available (I have my doubts about that)”

You are welcome to read the History. USC medical library has one of the 12 known copies. I have already mentioned that canister may well have caused wounds that I reviewed data on. I also said that typical shrapnel wounds, as we saw in WWI and WWI, where artillery was called “The Queen of Battle” and caused a high percentage of wounds contrary to Civil War experience, were not described.

Body armor is hardly a magic shield of invincibility. It’s heavy, reduces your field of view, and greatly reduces your mobility.