In my last two columns (See article links here and here) I have been following the thread of the US Navy’s visual and radio communications style and how it affected the US Navy’s night fighting and amphibious styles in the Guadalcanal/Solomons campaigns and during the landing at Tarawa respectively. Today’s column continues that US Navy communications thread and weaves it together with several other threads from previous columns including ones on

Ӣ Intra-service politics regarding sea mining in the Pacific War,

Ӣ Theater amphibious fighting styles,

”¢ A quirk of in promotion policy in the WW2 US Army’s military culture, and

Ӣ The Ultra distribution war between MacArthur and both the Navy & War Department intelligence mandarins

(See links here, here, here and here) so as to tell the story of how the US Navy’s interwar mania for controlling radio communications turned into a huge problem of interservice politics that hurt the war effort in the Pacific.

The US Navy’s fighting style, in the Pacific from Pearl Harbor through Okinawa, was characterized by naval centric “joint” warfare where the Navy was always first among equals and most staff work was done under Adm. Nimitz’s eyes. Where that “First among equals” theater fighting style rubbed the US Army wrong most heavily was with the Navy’s centralized style with radio communications.

There were reasons for this Navy style. The interwar US Navy investigations of the Royal Navy’s failure to destroy the German High Seas Fleet at Jutland in World War I (WW1) made it utterly controlling in its mania to minimize radio communications in order to deny the enemy the kinds of radio direction finding and code breaking intelligence the British Royal Navy had at Jutland.

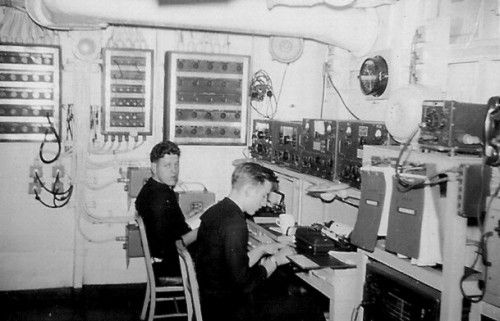

This mania for centralized control of radio communications had perverse battlefield outcomes during the late Solomans and early Central Pacific Campaign, which are chronicled by Dixie R. Harris and George Raynor Thompson in the US Signal Corps Green book SIGNAL CORPS: THE OUTCOME, (Mid-1943 Through 1945) in footnote 19 on page 210:

Late in 1942 a War Department General Staff observer, Col. Leonard H. Rodieck, reported on the message center in Noumea, where an acute accumulation of military messages had developed, as follows:

.

“The best set-up . . . was in Noumea.

.

. . . The Navy task force was in the harbor. General Harmon got all the Navy operators ashore to help out the Army, because the Navy was maintaining [radio] silence in the harbor. Noumea finally got caught up to within four days, with the Navy’s help, after being thousands of messages behind.”

Effectively in and around the period of the two major battleship engagements off Guadalcanal in late 1942, the US Navy shut down the majority of its Noumea headquarters’ radio communications, including all of its US Army supply and administrative traffic supporting the troops and aircraft on Guadalcanal!

Nor was this controlling behavior by the US Navy with Army radio communications limited to just whether Army communications were transmitted. The US Navy senior communications officers often changed the messages transmission priority and their content, based on what the Navy thought best and not what Army commanders requested. Again, from PAGES 209 210 of SIGNAL CORPS: THE OUTCOME, (Mid-1943 Through 1945):

Signal Relations With the Navy

Joint communications frequently characterized signal operations in the South Pacific Area, as in 1942 on Tongatabu, where a signal detachment of about fifty men, drawn largely from the 37th Division, set up a message center at Nukualofa. The Navy communications unit there not only handled cryptographic work for all interisland radio traffic, including Army signals, but even “reserved the right to delete or change any parts of messages which they did not consider necessary,” commented the somewhat miffed signal officer on the island, Lt. Col. Dane O. Sprankle.18

.

“In theory it is fine to consolidate,” Colonel Ankenbrandt once said, speaking of joint communications. But the difficulties in joint practice sometimes clashed with the theory. “Tongatabu, Bora Bora, and Samoa-Ellice Islands,” he wrote in January 1944, “are examples where such has been in operation and our operation (Army gets ‘balled up’ or delayed unduly.” He explained, “The Navy has minor differences in procedure and other rules and regulations contrary to our practice. Furthermore, the Navy is in practice now of ruling out practically all administrative traffic from their radio circuits, handling all of this stuff as ‘Airmailgram.’ Such procedure does not always suit our Army Commanders.” 19

US Navy Military Culture

Saying that naval officers are controlling is like saying water is wet. This is very much a matter of professional training. A ship’s captain is the unquestioned authority about everything on his ship and a senior ship’s captain knows more about everyone’s jobs on his ship than the people doing them (other than the senior chief of the ship). This tradition came from before the age of sail and continues to this day. (Whether or not that tradition is on-the-ocean reality is a different question…and the subject of a great many good novels.)

This background results in three institutional tendencies by the US Navy that make it hard for them to “play with others.” First, naval officers had a “We-Band-of-Brothers” or strong in-group versus out-group tribalism in terms of service cohesion. Think in terms of ships crews versus the sea and the naval bureaucracy. Second, naval officers had a strong tendency towards rules based hierarchical, centralized, bureaucracy as the default approach to command. And last, senior commanding naval officers carried that “I know how to do your job better than you do” attitude ashore and into situations that it is plainly not true. All three tendencies made themselves felt with the US Army’s radio logistical communications which the US Navy insisted upon controlling in WW2.

The Navy’s insistence on controlling Army communication extended to insisting that naval personnel send coded Army messages on Army code-cypher machines they were not trained upon. The results were predictable, as was the blow back from Washington DC. These three paragraphs come from Page 126 of the 7th Army Air Force section of “REFORT OF PARTICIPATION OF USAFICPA IN THE GALVANIC OPERATION,” 17 June 1944, Lt. Gen. ROBERT C. RICHARDSON commanding

w. Deviation between Army and Navy cryptographic practices

when working on joint systems tended to give away the organization

enciphering the message. CinCPAC in collaboration with the Seventh

Air Force, drafted a letter for submission of the differences to the

Combined Communications Committee in order that the deviations might

be overcome.

.

x. Both officer and enlisted men should be trained in the

operation of the ECM, and officers should be trained in all cryptographic

devices, Thorough instruction is now being given to all

cryptographic personnel.

.

y. Navy personnel are not always familiar with the Army

systems that are available in the Joint Communication Centers, which

results in many unnecessary “services.” the Cryptographic Security

Officer at ADVON Seventh Air Force, has sent a letter to the Joint

Communications Centers on checking Army system and Army indicators

before sanding “services.” In addition, all new cryptograph officers

are instructed to keep Navy personnel conscious of the presence of

Army systems in the Joint Communications Centers.

In so many words the Navy communications officers and enlisted men didn’t know how to use the Army cryptographic machines, used them anyway, used them badly, kept breaking them and WERE NOTICED DOING IT.

The blowback from War Department Observer reports and a separate American signals counter intelligence monitoring of American coded communications for compliance with good code practice resulted in a message subject titled “Communications Policies for Joint Operations in the Central Pacific Areas.” from Admiral Nimitz on 6 October 1943 telling his controlling naval communications officers the following on page two of the policy letter:

(d) In accordance with a directive from the Joint Chiefs of Staff to avoid duplication of circuits and facilities. fixed circuits shall be established only as

authorized by CinCPOA . This principle applies only to long range circuits employing frequencies below 20 mcs.**** Internal tactical circuits required by assault

or defense forces, tactical circuits required for air-amphibious operations, and circuits employing low power on frequencies above 20 mcs, are excluded from the provision.

.(1) Circuits or facilities, when authorized in accordance

with (d) above. Which are peculiar to

the needs of one service usually shall be provided

and operated by that service.

.

(2) Where circuits are employed jointly the service

having paramount interest shall provide and

operate such circuit or facility

In so many words, let the US Army run its own tactical communications and don’t break the Army code machines, it makes the US Navy look bad in Washington DC if you don’t.

US Army “Working Around”

To deal with this over controlling US Navy command style in the Pacific War, US Army and the emerging US Army Air Force began their own tradition of “Working Around” the Navy. They did this via lateral communications inside the Army to get around the control issues of naval officers in their chain of command. Both of the following examples of “Working Around” come from my earlier column “History Friday: MacArthur’s SWPA Intelligence” —

1) Pages 256 and 257 of the book “Piercing the Fog: Intelligence and Army Air Forces Operations in World War II,” that stated the following regards the US Navy’s refusal to provide Ultra signals intelligence to the 13th Air Force in 1943:

Because Admiral Halsey’s intelligence officer would not provide Harmon’s*** staff with a regular flow of ULTRA early in 1943, and over the objections of Halsey’s intelligence officer, Sherman arranged with General Willoughby to receive locally derived and Washington SIGINT information from Brisbane. Sherman sent as much of this material as possible to Twining and the Thirteenth Air Force A-2. 22

22. Diary, L. C. Sherman, AFHSO, pp. 12, 17, 21, 26-27..

2) The ultimate expression of “Working Around” in the Pacific was General Douglas MacArthur’s chief signal officer, General Akin, who created the South West Pacific Area (SWPA) Signal Corps “Command Post (CP) Fleet.” Essentially General Akin outfitted a series of radio relay ships from MacArthur’s small boat section (See my History Friday: MacArthur’s Mission X column) to act as a separate long range communication system completely independent of the US Navy.

The US Navy did not take this sitting down and took steps to exercise control in other more direct ways.

While “Working Around” was effective for MacArthur, who could draw on Australia for supplies independent of Navy controlled sea lanes and to a lesser extent with Army ground commanders in the Pacific. It was not hold true for the U.S. Army Air Force.

First, as can likely be gathered from the excerpted 7th Army Air Force communications section above, there was very little love lost between them and the Navy. The 7th Army Air force showed Washington D.C. high command the Navy really didn’t know the Army’s job better than the Army did. For that and for other issues during Operation Galvanic that I will go into in another column, Admiral Nimitz distrusted Army flyers and took steps to keep them under more positive control.

Adm. Nimitz made a MacArthur-like chain of command arrangement (See MacArthur’s “Alamo Force” command arrangement to side line Australian General Sir Thomas Blamey in my History Friday — MacArthur: A General Made for Another Convenient Lie column) and organized the 7TH Air Force after Galvanic so that each of its combat elements was under a US Naval task force with a US Navy commander. This reduced the headquarters 7th Army Air Force into an ill-tolerated administrative entity.

There were unexpected and bad results from this action. Adm. Nimitz had cut the US Navy off from the land based radar lessons the 8Th and 9th Army Air Forces in Europe learned and passed on to the 7th Air force about using land based radar networks to gain air superiority. This lack of effective land based radar net deployment skills would be seem later in the horrible destroyer picket losses in the Okinawa campaign.

Thus it would remain until Late 1944, when the Army Air Force bomber clique’s 20th Air force arrived in the Pacific and wrote a completely new chapter in “Working Around” which will be the subject of my next column.

*** Please note that the “General Harmon” referred to above was the US Army Air Force commander of the 13th Air Force under Southern Pacific (SoPac) Theater commander Admiral Halsey, later Harmon was Halsey’s assistant SoPac commander and finally he was the South Pacific Theater commander when Nimitz promoted Halsey to run Third Fleet. Harmon disappeared in a plane crash in February 1945 while flying to Washington D.C. to try and unsnarl the command mess Nimitz made of the Pacific Army Air Force.

**** mcs Radio frequency in Megacycle or more commonly Hertz

Sources and Notes:

Dixie R. Harris and George Raynor Thompson, UNITED STATES ARMY IN WORLD WAR I, The Technical Services, THE SIGNAL CORPS: THE OUTCOME, (Mid-1943 Through 1945) See pages 209-210 for ”Signal Relations with the Navy” and pages 260 265 for the “CP Fleet”

John F. Kreis ed., “Piercing the Fog: Intelligence and Army Air Forces Operations in World War II,” Air Force History and Museums Program, Bolling Air Force Base, Washington, D.C., 1996, pages 256 and 257,

Link: http://www.afhso.af.mil/shared/media/document/AFD-101203-023.pdf

Trent Telenko, “History Friday: MacArthur’s SWPA Intelligence,” June 7 2013

Link: https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/36590.html

Trent Telenko, “History Friday: MacArthur’s Mission X,” July 19, 2013

Link: https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/37265.html

Trent Telenko, “History Friday — MacArthur: A General Made for Another Convenient Lie.” July 26, 2013

Link: https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/37267.html

Trent Telenko, “History Friday: MacArthur’s Amphibious Fighting Style & Operation Olympic,” August 16, 2013

Link: https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/38075.html

Trent Telenko, “History Friday: American High Command Politics, Sea Mining and the Invasion of Japan,” October 25, 2013

Link: https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/38592.html

Trent Telenko, “History Friday: Pacific Paradigm Shift in the US Navy,” January 24, 2014

Link: https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/41324.html

Trent Telenko, “Tarawa and the Role of the USN’s Visual Communication Style,” January 31, 2014

Link: https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/41455.html

Trent, try this site: http://www.ozatwar.com/sigint/cbi.htm

Aussie codebreakers.

Just wondering if miscommunication between army and navy caused the battle of the “Tin Can Sailors” that saved the invasion fleet. You had previously detailed its failure on Guadalcanal. I know the phrase “the world wonders” was filler; however, what was the communication like between army HQ and the various fleets. It is still hard to imagine that a Japanese anti-invasion fleet got so close.

“senior ship’s captain knows more about everyone’s jobs on his ship than the people doing them (other than the senior chief of the ship).”

An absurd claim at best. I doubt any ship’s captain knows how to repair a catapult on a carrier, stitch a serious wound or perform most of the myriad functions performed by the various ratings or by the various and assorted department heads. To know more about everyone’s jobs than everyone else is no the function of a skipper. As skipper commands men. End of story.

Re ship’s captains and detailed knowledge of jobs on-board, see my post Decision-Making in Organizations, which excerpts a story from a naval officer serving on a destroyer.

“Just wondering if miscommunication between army and navy caused the battle of the “Tin Can Sailors” that saved the invasion fleet.”

I think it was absent communication rather than “mis-“.

Halsey sent information copies of this message to Admiral Nimitz at Pacific Fleet headquarters and Admiral King in Washington. but he did not include Admiral Kinkaid (7th Fleet) as information addressee.[11] The message was picked up by 7th Fleet, anyway, as it was common for admirals to direct radiomen to copy all message traffic they detected, whether intended for them or not. As Halsey intended TF 34 as a contingency to be formed and detached when he ordered it, when he wrote “will be formed” he meant the future tense; but he neglected to say ‘when’ TF 34 would be formed, or under what circumstances. This omission led Admiral Kinkaid of 7th Fleet to believe Halsey was speaking in the imperative, not the future tense, so he concluded TF 34 had been formed and would take station off the San Bernardino Strait. Admiral Nimitz, in Pearl Harbor, reached exactly the same conclusion. Halsey did send out a second message at 17:10 clarifying his intentions in regard to TF 34:

Unfortunately, Halsey sent this second message by voice radio, so 7th Fleet did not intercept it

7th fleet was “MacArthur’s navy” and excluded from Halsey’s plans. This almost ended in disaster and should have resulted in Halsey’s relief but “The Tin can sailors” saved him. Later, he made a second blunder with the typhoon but John McCain got the blame for that and was relieved. McCain died soon after.

RonaldF,

The US Navy has been blaming MacArthur for that Leyte communication fowl up for going on 50 years, which I touched on in an earlier column.

The evidence, as opposed to the rhetoric from certain admirals, supports it being strictly a US Navy “Charlie Foxtrot.”

Aspects of American Leyte radio communications are in the “idea hopper” for a future column, but not anytime soon.

wpapke said:

>>An absurd claim at best.

It was actually true in the time of sail and the US Navy was, at best, two generations from the sail age in WW2.

Part of the issue is that at the time of sail a captain’s ‘expert badge’ covered everything a rating did on his ship.

The arrival of steam and electricity changed that.

There is no doubt the skills set at senior officer level had been left behind by technological change — see the radar night-fighting command issues in the Solomons — but the tradition of ship captain (and higher rank) arrogance was still there.