The passages below are from the really excellent book How We Got To Pekin: A Narrative of the Campaign in China of 1860 by Robert James Leslie M’Ghee (1862)

Now for the far-famed Takoo Forts. They are five in number, two upon the left, or north bank of the river, and three upon the south bank. The two upper Forts, north and south, are nearly opposite to each other. About three-quarters of a mile further down lies the second north Fort, and below it, about 400 yards upon the south bank, the one upon which our unsuccessful attack was made in 1859, and the fifth lies close to the mouth of the river upon the same side; there is a strong family likeness among them all.

Our attack was to be made upon the upper northern Fort, and it was on this wise. At day- light on the 19th Sir R. Napier, who was to command the assault, marched out of Tankoo with the 67th Regiment, Milward’s battery of Armstrong guns, the Royal Engineers, and Madras Sappers, for the purpose of making roads over the soft part of the mud, bridging the numerous canals, and throwing up earthworks to protect our artillery, and no man could have been chosen more fitted for the task, being himself an engineer officer of great experience, and a tried and skilful general.

(This is Napier, at a later period of his very successful military career.)

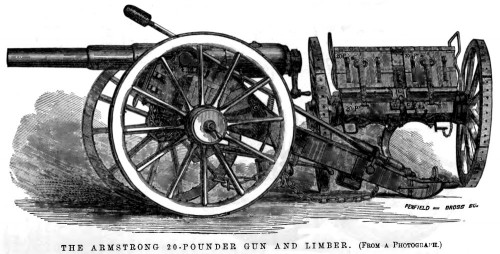

The war against China was a splendid opportunity to try out the latest equipment. The British brought with them the new Armstrong breach loading cannon.

One chief interest in this campaign has been to watch the first trial of the Armstrong guns, and I was soon down at the edge of the river at the south gate of Tankoo, watching our fire and that of the enemy; as usual, the direction of the Chinese guns was good, but the elevation defective; they sent their shot either short or over our heads, and during that morning not one shot came nearer than within twenty yards of our guns. Not so the Armstrong shells; the first few were short, and burst in the water, but soon they got the range, and then you could see the dust fly, as the shell struck the battery, nor was it long until their fire was slackened, and they were eventually silent. Mr. Hosier, R.A., is the officer who has the credit of that morning’s work at Tankoo.

As it happened, the concept of breech loading artillery was sound, and was in fact the wave of the future. But as sometimes happens with new technology, the first use of this new approach was unsuccessful. In the case of the Armstrong, they were comparatively expensive to make, and complex to operate. The Armstrongs performed well when they worked, but broke down and were unreliable and difficult to use. The British actually went back to using muzzle loading cannon, which would predominate for a few more years, including during the American Civil War which would break out a few months after these events on the other side of the world.

Imagine being part of the Chinese artillery crew, subject to what later generations would call counter-battery fire. You can see your shot is not hitting the target, there is something wrong with your methods, but the day of battle is upon you, it is do or die, and it is too late now to learn how to do it properly. Meanwhile the British guns, after the first few shots, are right on the mark, killing and maiming the men around you, and smashing up your guns, until you and your fellows are dead or incapacitated, or your guns are wrecked, or both. Mr. Hosier of the Royal Artillery made a short morning’s work of you, and you could do nothing effective in response. It must have been a miserable experience, up to the moment it became personally lethal, to be outgunned and outclassed in this manner. (Incidentally, Hosier, with the rank of captain, went on be mentioned in dispatches during the Abyssinian Campaign as having evinced “great energy and practical ability”.)

To make things worse, the Chinese gunners were actually tied to their guns by their commanders so they could not run away, according to Robert Swinhoe, an eye witness to the attack on the forts.

Numbers of dead Chinese lay about the guns, some most fearfully lacerated. The wall afforded very little protection to the Tartar gunners, and it was astonishing how they managed to stand so long against the destructive fire that our Armstrongs poured on them; but I observed, in more instances than one, that the unfortunate creatures had been tied to the guns by the legs.

Swinhoe’s book Narrative of the North China campaign of 1860; containing personal experiences of Chinese character, and of the moral and social condition of the country; together with a description of the interior of Pekin (1861) is very good as well, though M’Ghee brings a more personal touch to the story which I found engaging.

The British artillery began to pound the forts, preparatory to the infantry assault.

Milward’s Armstrongs were the first to open the ball upon our side, and in a short time every gun we had was in action, and a fearful storm of shot and shell was poured into the devoted Forts, while the Chinese maintained their fire with determination for more than two hours. A tremendous explosion took place in the upper north Fort at about six o’clock, occasioned by the blowing up of a magazine by one of our shells, and another soon after was exploded in the lower fort on the same side … .

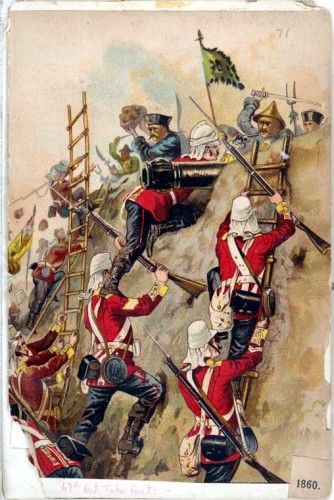

The infantry then had to get across a moat, then scale the walls.

… [The] Royal Marines were endeavouring to bridge with very nice-looking pontoons, which had doubtless been tried and answered admirably upon the Serpentine, but proved themselves of no use here, as being unweildy; all the exertions of Major Graham and both the Sappers and Marines proved unavailing; both he and the officer commanding the Marines were wounded, and a large proportion of their men, before they desisted from their vain attempts, and at last a plank was obliged to perform that important duty, but not before a number of both regiments had crossed by wading up to their necks and swimming.

A perfect storm of matchlock and gingall balls was poured firom the walls upon the storming and pontoon parties,’ together with arrows, spears, and shot, stinkpots, and lime-baskets, enough to have damped the courage of any troops except those engaged ; but neither the English or French ever gave way an inch or faltered for a moment. Ladder after ladder was thrown back upon the assailants or dragged over the wall; officers and men were thrust back wounded from the embrasures; at length Mr. Rogers of the 44th managed to scramble through an embrasure, although wounded in the act, at the same time as the French entered from the angle next the river.

The infantry managed to get over the wall.

Note that the British officers led from the front. The incredibly aggressive performance by British officers throughout this era, with the expected high rates of injury and death, is something that amazed their enemies, and is really not fully explained to this day. It seems it was simply the ethic of the service that officers led attacks in person. Also, there was a desire to be mentioned in despatches or awarded medals, and visible feats of courage were necessary to be granted these honors. Conspicuously gallant officers were more likely to be promoted. Also, there was a belief that native troops were impressed by death defying bravery, but that they could not be led by officers whose personal courage was suspect. Thus, an officer in command of native troops, in particular, must show the utmost courage, not only in the attack, but aplomb and coolness in the face of danger or enemy fire. Sir Robert Napier, pictured above, rose to high rank. But in his early career he was repeatedly wounded, including personally leading the attack into the Sikh camp at the ferocious battle of Ferozeshah.

Garnet Wolseley, in his memoirs, describes the feeling of leading one of these attacks. He led a charge against a bandit fort in the jungle of Burmah.

”¨No one in cold blood can imagine how intense is the pleasure of such a position who has not experienced it himself; there can be nothing else in the world like it, or that can approach its inspiration, its intense sense of pride. You are for the time being, and it is always short, lifted up from and out of all petty thoughts of self, and for the moment your whole existence, soul and body, seems to revel in a true sense of glory. The feeling is catching, it flies through a mob of soldiers and makes them, whilst the fit is on them, absolutely reckless of all consequences. Oh! That I could again hope to experience such sensations! I have won praise since then, and commanded at what in our little Army we call battles, and know what it is to gain the applause of soldiers; but, in a long and varied military life, although as a captain I have led my own company in charging an enemy, I have never experienced the same unalloyed and elevating satisfaction, or known again the joy I then felt as I ran for the enemy’s stockades at the head of a small mob of soldiers, most of them boys like myself.

In this attack Wolseley was shot by: “… a large jingall bullet through the upper part of my left thigh. I tried to stop the bleeding withy my left hand, and remember well seeing the blood squirting in jets through the fingers of my pipe-clayed gloves. I cheered and shouted, and waved my sword, calling upon the men to go on.”

This is the kind of conduct that led to either an early death or promotion and prestige in the Victorian era British army.

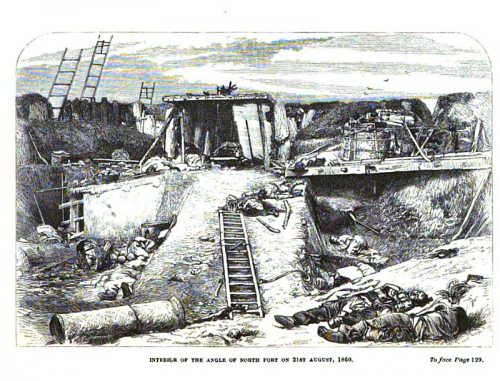

Back at the Taku forts, the infantry found all was havoc inside, wrought by their artillery.

The scene inside the Fort is hardly to be described, the Tartars fighting still with desperation against fearful odds, even their wounded, shooting at our men as they passed, for numbers of both French and English were now inside. Colonel Anson and Colonel Mann cut down the drawbridge across the ditch, which the former with Captain Grant had swam on horseback, until their horses stuck, when they left them there and struck out on their own account. But while some fought thus desperately, others fled, but only to meet their fate outside the Fort; many were shot down and transfixed by the sharp bamboo spikes which extended between the wall and the ditch for twenty or twenty-five feet in width, and lay there a fearful spectacle; many were drowned endeavouring to cross the river, and the havoc which our fire had made, caused it to be a matter of wonder to everyone that they should have held out so long and so gallantly as they did. Their dead lay in heaps round their guns and scattered through the Fort, bearing witness to the excellence of our weapons, and the accuracy of our fire.

Note that M’Ghee calls the enemy troops Tartars because China was at that time ruled by the Manchus, who were also called Tartars. The Manchus conquered China in 1644, and founded the Qing or Ch’ing Dynasty, which lasted until 1912.

This campaign was during the overlap between two eras of warfare. The older era, from time immemorial, up to and through the days of muzzle loading cannon and muskets, was still one in which battles were decided by closing with the enemy with the sword or the bayonet. Firepower simply weakened the enemy for the assault. But the modern era, which we live in to this day, is one of “radical lethality” based on firepower, primarily artillery, which came to dominate in the First World War. (The phrase “radical lethality” is from an excellent book by Stephen Biddle called Military Power: Explaining Victory and Defeat in Modern Battle.) We get a glimpse of that the radical lethality to come in this early episode.

I have previously written about Victorian memoirs of wars in 19th Century China on the blog, including these posts:

What is the best book you read in 2010?(Discussing Garnet Wolseley’s memoirs, including his service in China.)

The End of the Tai-ping Rebellion

The Birth of the Ever Victorious Army

There are several links to excellent books in these posts.

Impressive story … impressive man, mustache and man-spreading. Any idea of the significance of the ring of keys?

He was Constable of the Tower of London after he retired from the military.

“Each Constable is now appointed for five years. The new Constable is handed the keys as a symbol of office. On State occasions the Constable has custody of the Crown and other royal jewels. The Constable enjoys the privilege of direct access to the head of state, HM the Sovereign.”

The ceremony of the of the keys would be worth seeing. Eisenhower mentions seeing it in his memoir.

Ah … thought the keys might have been significant.

Sigh … what a nice-looking, Victorian man: competent, intelligent, and brave. Probably had very nice manners, too. Such a contrast to Pajama-boy. There is good reason for me liking the 19th century so much. They were real men, back in that day.

“There is good reason for me liking the 19th century so much.”

It is very important to read the memoirs or at least books written at the time.

Modern, secondary sources cannot help but put a contemporary filter on things.

But it is misleading.

They were different from us, the Victorians. It is a different moral and mental world. It can be subtle.

I talked about that here

I find that I prefer to be there than here.

Though since I am corporeally here, I have little choice about it.

One from that thread that was good, but biased was “The Discovery of Insulin: 25th Anniversary Edition by Michael Bliss”

That is an interesting story that Bliss gets partly wrong. He gives far too much credit to MacCleod who let Banting and his medial student assistant Best use his lab for the summer while he went fishing in Scotland. When he came back, he claimed credit for their work, not the first example of that phenomenon. Banting and MacCleod got the Novbel Prize while Best was excluded. The story is here. Banting was killed early in WWII and MacCleod had no further accomplishments of note. Best went on to a great career.

The Nobel Committee won;t allow copying of the citation but it relates how Banting was furious that Best was excluded.