It is amazing the things you find out while writing a book review. In this case, a review of Phillips Payson O’Brien’s How the War Was Won: Air-Sea Power and Allied Victory in World War II. The book is thoroughly revisionist in that it posits that there were no real decisive land battles in WW2. The human and material attrition in those “decisive battles” was so small relative to major combatants’ production rates that losses from them were easily replaced until Anglo-American air-sea superiority — starting in the latter half of 1944 — strangled Germany and Japan. Coming from the conservative side of the historical ledger, I had a lot of objections to O’Brien’s book starting with some really horrid mistakes on WW2 airpower in the Pacific.

You can see a pretty good review of the book at this link — How the War Was Won: Air-Sea Power and Allied Victory in World War II, by Phillips Payson O’Brien

However, my independent research on General MacArthur’s Section 22 radar hunters in the Philippines proved one of the corollaries of O’Brien’s thesis — Namely that the Imperial Japanese were a fell WW2 high tech foe, punching in a weight class above the Soviet Union — was fully validated with a digitized microfilm from the Air Force Historical Research Agency (AFHRA) at Maxwell AFB, Alabama detailing the size, scope and effectiveness of the radar network Imperial Japan deployed in the Philippines.

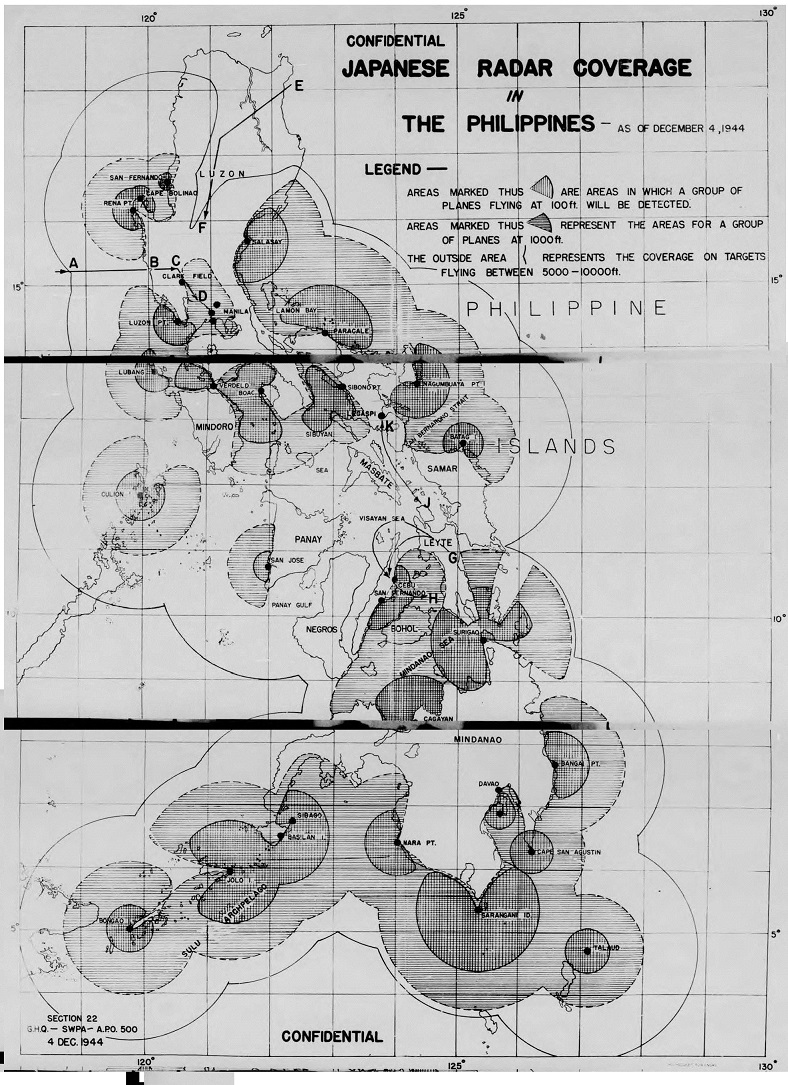

The microfilm reel A7237 photoshop below is a combination of three scanned microfilm images of an early December 1944 radar coverage map of the Philippines. It shows 32 separate Imperial Japanese Military radar sites that usually had a pair of Japanese radars each (at lease 64 radars total), based upon the Japanese deployment patterns found and documented in Section 22 “Current statements” from January thru March 1945 elsewhere in the same reel.

This Section 22 created map — taken from dozens of 5th Air Force and US Navy aerial electronic reconnaissance missions — showed Japanese radar coverage at various altitudes and was used by Admiral Halsey’s carrier fleet (See route E – F on the North Eastern Luzon area of the map) to strike both Clark Field and Manila Harbor, as well as by all American & Australian military services to avoid Japanese radar coverage to strike the final Japanese military reinforcement convoys, “Operation TA”, of the Leyte campaign.

A Japanese Technological-Logistical Tour-d-Force.

As Assistant director of Section 22, General Headquarters (GHQ) South West Pacific Area (SWPA) Col. Paul Albert stated in this passage from Current Statement No. 0259 – 13 January 1945:

RADAR LOCATIONS

At the time that the map was compiled, the disposition of completed and scheduled Japanese radars was apparently around the EASTERN perimeter of the PHILIPPINES and along the WEST coast of LUZON. This is supported by intercept evidence which suggests that the Present extensive radar network within the PHILIPPINES was not established until some time after the initial landings.

The Section 22 radar coverage map is dated early December 1944. Leyte was invaded on 17 October 1944.

The microfilm reel mentions that MacArthur’s forces captured and translated a Japanese document showing the plan to deploy those radars that happened in the course of the Leyte ground fighting. The Imperial Japanese military not only moved 30-odd radars in the middle of one of the largest Allied invasions of World War 2, but they had pre-surveyed sites in mind for them to deploy to. That was a technological-logistical tour de force.

By way of comparison, it took from 30 March 1945 to mid-July 1945 for the US Marines at Okinawa to deploy 30(+) land based radars on and around Okinawa. After a similar time period of 45 days the USMC had only 17 radars in place. And during Operation Husky — the summer 1943 Anglo-American invasion of Sicily — The Allies deployed 40 mobile land-based radars in 39 days between 9 July 17 August 1943.

Japanese military doctrine of the time was to have at least two radars at a radar site of different frequencies and low altitude coverage performance. This was so one radar could track a target while the other searched. This also resulted in fewer gaps in radar coverage.

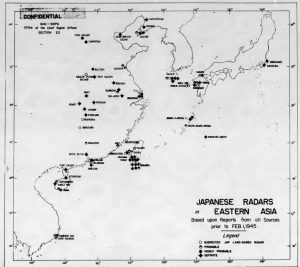

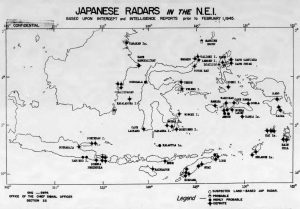

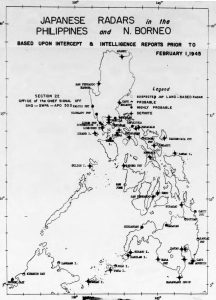

What this doctrine meant, in terms of rapid redeployment, was that the Imperial Japanese military could skin one radar per site on Borneo, the Chinese coast, Formosa, Ryukus and Japanese Home Islands to flex that many radars into the Philippines that quickly. See the three February 1945 Section 22 suspected radar site maps below to get an idea of how large a reserves of radars the Japanese military had to draw upon to fill the gaps in Philippines radar coverage.

Plus also note below the radar deployment changes by the Imperial Japanese military in the Philippines between Dec. 1944 and early Feb. 1945.

The most interesting fact of these Philippines radar network deployments was that they were a joint IJN/IJA effort.

The captured Japanese planning documents showed a consistent siting of an Imperial Japanese Army radar along side an Imperial Japanese Navy radar and many aerial photos taken at the time confirmed radar types unique to the Japanese Army and Navy sited adjacent to one another.

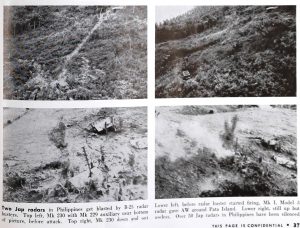

Section 22 didn’t know at the time the significance of that fact. They were tracking radar types without real organizational-analytical regard to which Japanese military service that was using them. The objective was to get useful radar coverage data to Allied airmen in order to save lives & aircraft and when possible kill Japanese radars. See Section 22 strike photo below.

However, post-war, the level of Japanese military cooperation in the Philippines as compared to the home islands would have been obvious.

Yet the final radar reports of General Kenney’s Far Eastern Air Force (FEAF), the relevant United States Strategic Bomber Survey reports and the U.S. Naval Technical Mission to Japan (AKA “NavTechJap”) could only talk about the separate IJA and IJN early warning reporting networks in the Japanese home islands. And there isn’t a word of this cooperation in the US Army, US Air Force, US Navy institutional histories, nor are they in MacArthur’s Reports.

This blackout appears to be partly a matter of keeping what we now call “electronic warfare” capabilities classified, and mostly a result of suppressing a number of WW2 combat histories in the War & Navy to Defense Department merger. The controlling institutional factions of the US Navy and USAF (CINCPAC and the Bomber Generals, respectively) were particularly ruthless about altering wartime reports that threatened their post-WW2 budgetary interests.

This is not unusual, such politics are part of the human condition.

The thing that stands out in this particular case was the suppression of the size, scope and capability of Japanese military-technological culture to deploy over 30 land-based radars across an area the size of the Philippines in a month and a half.

I will be exploring this “hidden narrative” of Japanese military-technological culture in future columns.

REFERENCES

1) George K. Grande, Sheila M. Linden, & Horace R. Macaulay, CANADIANS ON RADAR, ROYAL CANADIAN AIR FORCE 1940 – 1945 Page VIII-6, Canadian Radar History Project; 1st Edition (2000)

See also downloaded copies at www.rquirk.com/cdnradar/cor/main.htm which provided the background on Anglo-American Radar deployment in Operation Husky.

2) Microfilm Reel A7237, filmed 8-12-75 by Archives Branch of the Albert F. Simpson Historical Research

Center at Maxwell AFB, Alabama, with the following Section 22 files used in this column —

o Maps of Japanese Radar, Dec 1944, Signal Corps File 710.654A

o Japanese Radio & Radar Activities, Jan 1945, Signal Corps File 710.654A

o GHQ SWPA Japanese Radar, Oct – Dec 1944, Signal Corps File 710.654B

o GHQ SWPA Japanese Radar, Nov – Dec 1944, Signal Corps File 710.654B

3) Evaluation of Photographic Intelligence in the Japanese Homeland, PART SEVEN, ELECTRONICS, PHOTOGRAPHIC INTELLIGENCE SECTION, Date of Survey 7 Oct 1945 through 16 March 1945, Final Report June 1946, United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS) Report #104

4) REPORTS OF THE U.S. NAVAL TECHNICAL MISSION TO JAPAN, 1945 1946, Operational Archives, U.S. Naval History Division, Washington, D. C.

http://www.fischer-tropsch.org/primary_documents/gvt_reports/USNAVY/USNTMJ%20Reports/USNTMJ_toc.htm

JM-200-B Series E: ELECTRONICS TARGETS

E-03 Japanese Land Based Radar

E-04 Japanese Centimeter Wave Techniques

E-07 Japanese Radar Counter-measures and Visual Signal Display EquipmentJM-200-F SERIES O: ORDNANCE TARGETS

0-56(N) Japanese Field and Amphibious Equipment Kyushu Defense Systems

5) A Short Survey of Japanese Radars Volumes I, II, & III, 20 Nov 1945, Prepared by 2d & 3d Operations Analysis Section, FEAF and Air Technical Intelligence Group, FEAF (ATIG Report No. 115)

6) Spreadsheet of USMC Radar Deployment at Okinawa, Author created compilation of radar deployment dates from War Diaries and War Histories Marine Air Group 43, and Marine Air Warning Squadrons One, Six, Seven, and Eleven, March – June 1945, downloaded Fold3 digitization service during 2014-2016 inclusive.

Did the Japanese Navy ever get radar placed on ships ? They certainly didn’t have it in 1942 at Guadalcanal. I don’t know that they had it at Leyte Gulf.

If they had, they might have realized that the Taffy 3 group was not Halsey.

I finished “The Rising Sun” and it is excellent.

A point from all the maps above, the Imperial Japanese Military radar network in Feb 1945 covered a much larger amount of air space than that of the British military at the same time.

>>Did the Japanese Navy ever get radar placed on ships ?

Yes, and several types, including a 10cm wavelength surface search radar with a independently invented Japanese cavity magnetron.

>>They certainly didn’t have it in 1942 at Guadalcanal

The Japanese navy went a different technological route before WW2 to fight at night.

They specially trained and selected observers with excellent night vision, created the best night time high magnification optics of any WW2 navy, as well as developing vitamin supplements that enhanced those specially trained night observer’s vision.

The IJN ordnance gurus also made a special flashless propellant for their naval rifles so they would not give away their position when they opened fire.

Against early meter band radars and high flash US Navy propellant through 1942, the Japanese made the better choice.

It was only when the microwave SG radar and it’s television like plan position indicator (PPI) radar display that the US Navy leapt ahead.

>> don’t know that they had it at Leyte Gulf.

Some of the battleships of Adm Kurita’s northern attack force at Leyte had gunnery radars. They were not very good as they meter band and lacked more advanced radar displays to determine whether they were shooting at Japanese Cruisers or Destroyers or at American ships beyond them.

“It was only when the microwave SG radar”

At the Battle of Guadalcanal, Ching Lee had it and knew how to use it. Dan Callaghan did not know how to use it and was a staff admiral who found himself in a battle to the death. He died bravely but incompetently.

Thanks Trent. It got me reading about the development of the cavity magnetron, SG radar (which is S-band radar, model G) and the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

Obrien seriously overreached in his assertion. Had he limited it to the Pacific War he might have had a better position.

A decisive action is one that precludes an opponent’s achieving his specific goal.That goal, whether tactical or strategic, would provide one side with the ability to determine the actions of the opponent. Midway and Alamein both decisively ended endeavors to establish commanding positions at geographical focal points of enemy resistance.

Midway was both a defensive and offensive threat to American seapower. Japan’s failure to acquire it while being materially damaged in the attempt completely reversed the dynamics in the Pacific. That this result was achieved almost solely by Air/Sea power buttresses his claim. Japan’s efforts from that point are entirely defensive. Their momentum was exhausted, decisively. The land battles thereafter were all outgrowths of American Air/Sea dominance.

Alamein, the land battle, decisively ended Axis advance upon the extremely vital chokepoint of Suez. While the author may argue that the eventual preponderance of Allied Air/Sea power was the decisive factor, it could also be argued that Allied intelligence, through the reading of Luftwaffe Command’s coded messages provided the decisive edge for the Allied navy to interrupt Rommel’s supply chain for fuel and reinforcements. Regardless of the many factors leading to it, the Nazi defeat and the near destruction of their army was decisive in precluding them from further entertaining their desires upon Suez.

Likewise, the Soviet capture/destruction of an entire army at Staligrad was decisive precisely as Midway was because it reversed the momentum of the war. Germany was entirely defensive after the loss of Paulus’ army. The author cannot realistically suppose that Soviet Air/sea power determined the battle which so decidedly interrupted Axis advance.

Pearl Harbor was Yamamoto’s operation and was a huge strategic mistake.

Midway was also Yamamoto’s but it was a result of Doolittle’s raid which baited the Japanese and had immense strategic consequences.

Thomas Hazlewood.

Actually, Obrien’s point was more confirmed by Alamein than refuted.

Alamein, the land battle, rested on a hing of fate known as Operation Pedestal. The resupply convoy that saved Malta as a air-sea base for the British.

See:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Pedestal

In September, with Malta supplied, Allied forces sank 100,000 long tons (100,000 t) of Axis shipping, including 24,000 long tons (24,000 t) of fuel destined for Rommel, leaving the Axis forces in Egypt consuming supplies faster than receipts, contributing to tactical paralysis during the Second Battle of El Alamein (23 October – 11 November) and Operation Torch (8–16 November).

Also see:

Operation Pedestal. The Crucial Malta Convoy of 1942

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=teTiIxRereg

With four carriers and two battleships in the British fleet, Operation Pedestal was the biggest Allied carrier fleet action in Europe. Only Midway, Leyte and the Marianas Turkey shoot were larger in the Pacific.

Trent – more wonderful stuff. You HAVE to eventually put all of your posts/research into book form.

“Germany was entirely defensive after the loss of Paulus’ army”

See the Battle for the Narva Bridgeheads in the winter & spring of 1944. The Germans with Estonian and Finnish volunteers and Danish conscripts stopped the Soviet advance. They launched a counteroffensive that badly beat back the Soviets who only recovered later in the summer when German units had to be pulled off the Eastern Front to fight the Anglo-American invasion. The swamps of Estonia provided ideal choke points to squeeze and annihilate the Red Army.

It’s important that we know about this history because our 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment, one of only two US Army combat units left in Europe, is in Estonia right now for exercises

https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=1098183163553444&id=281487588556343

Malta was more crucial to the allies than Midway was for the the Americans, yet the Germans did not go after it.

They took Crete which was a sideshow.

I’m on a Civil War bent right now then will have to get back to WWII.

I did some reading about Waterloo before our trip last September. Bernard Cornwall’s book, Waterloo, is essential for anyone wanting to understand that battle. I spent years reading about Napoleon’s campaigns but the subject is so vast you get lost, Does anyone know what the military schools, like West Point, select for reading?

Cornwell’s “Saxon Tales” are also excellent and I have read the first six or so.

Then, when the urge strikes, I have to plow through Genetics again. Heavy going but all medicine is going that way. The New England Journal has a couple of articles a week you can’t understand without genetics.

For example.

We identified 5234 driver mutations across 76 genes or genomic regions, with 2 or more drivers identified in 86% of the patients. Patterns of co-mutation compartmentalized the cohort into 11 classes, each with distinct diagnostic features and clinical outcomes. In addition to currently defined AML subgroups, three heterogeneous genomic categories emerged:

5234 mutations in 76 genes for acute leukemia.

Writing to make sure your Okinawa radar reference spreadsheet (Ref 6) is complete. AWS-8 also participated in the Battle of Okinawa and their numbers should be included. Great article as always.

I’d have to agree with the statement that “there are no decisive battles” in modern warfare. That was proved in WWI. Modern mass militaries are just too big to beat via a “desisive battle”. Stalligrad, Midway, Alamein, etc. were major victories. They also, in retrospect, mark turning points in the greater conflict. But modern wars are won by many victories on many fronts.

I have to totally disagree on winning wars via naval ard air power alone. All three are needed.

wkg_in_bham,

This —

>>I have to totally disagree on winning wars via naval and air power alone.

…is not what O’brien said.

This passage from the review I linked to puts in a nutshell the argument O’brien made.

Conventional wisdom asserts that the Soviet Union made the decisive contribution to Allied victory in the great land battles fought on the Eastern Front. The core reason for this “extraordinary consensus”, O’Brien asserts, “is the underlying assumption that manpower in armies is the determining measure of national effort”. To the contrary, what was truly decisive was the role of America and Britain in achieving predominance in air and sea power, and it was this that destroyed Germany’s and Japan’s ability to fight effectively and led to their defeat.

What won the war were not battles in the conventional sense of engagements limited in time and space, but what O’Brien terms “super-battles”, in which the UK and US fought an air and sea war on battlefields thousands of miles in length and breadth, areas that dwarfed the land war and which allowed for a far more systematic destruction of German and Japanese weaponry and munitions than was achieved by conventional battles.

These super-battles were fought over years and involved home economies and their capacity for production. That their importance was recognised was attested by the importance that all the great combatant powers, with the exception of Russia, attached to the manufacture of aircraft and ships as they geared their economies by a large proportion to their manufacture above that of armoured fighting vehicles.

Once Anglo-American dominance in the air and at sea was won, as it was in the super-battles in the Atlantic and Pacific – and, after the painful lessons of the earlier strategic bombing campaigns, in the skies above Europe – the Axis war effort was progressively destroyed. O’Brien categorises the methods of destruction as attacks upon the pre-production, production and deployment of weaponry, including aircraft and ships, and armaments; the first prevented weapons from even beginning to be made, the second saw their destruction as they were being made, and the third prevented them from ever being used in battle.

Such a thoroughgoing revision of the history of the war will outrage many historians. It will be argued that it seriously underestimates the importance of armies and land warfare; after all, only armies can take and occupy territory.

O’Brien has, however, made a strong case, backed up by a mass of statistical evidence, for the overwhelming importance of Anglo-American air and sea power. The success of D-Day and the Normandy campaign would probably have not been possible without it, nor would the US Army Air Forces and the RAF have been able to prevent the deployment of German forces without it.

There are huge weaknesses in his argument WRT Pacific war plans (Formosa versus the Philippines), PAcific aircraft range and not enough attention to radar as a part of air power. He also misses the connection of earlier Me-262 deployment & advanced German submarine designs he went on at great length about.

Mark M.

My spread sheet has the AWS-8 deployments.

I’ll update the foot note.