I have often stated in an earlier Chicago Boyz columns on Gen Douglas MacArthur that:

“One of the maddening things about researching General Douglas MacArthur’s fighting style in WW2 was the way he created, used and discarded military institutions, both logistical and intelligence, in the course of his South West Pacific Area (SWPA) operations. Institutions that had little wartime publicity and have no direct organizational descendant to tell their stories in the modern American military.”

Today’s column is on another of those forgotten institutions, the New Guinea Air Warning Wireless (NGAWW) company, and the US military leader who saw to it that it’s story was forgotten in the institutional American military histories of World War II.

DESPERATION & INNOVATION

In January 1942 — after the Fall of Rabaul and before the Japanese Carrier Strike on Darwin — the Australian military recognized it needed a system of radio equipped ground observers in New Guinea to warn Australian outposts of incoming air attacks. Thus was born the New Guinea Air Warning Wireless Company (NGAWW), which was a inspired combination of innovation and desperation using the organizational templates (and Amalgamated Wireless Australasia (AWA) Teleradio series wireless sets) of the Australian Royal Navy Coast watchers and the Royal Air Force Wireless Observer Units used in North Africa. [1] [2]

The NGAWW was born as a “secret wireless unit” in January 1942, give a status as a “commando unit” in 1944 and was officially disbanded in April 1945. [3]

In early Jan-Feb 1942 some 16 air warning ground observer stations were established. There were positions set up along the Papuan coast as well as in the mountains near Port Moresby. By Dec. 1942 the New Guinea air warning network had quadrupled in size and was maintaining 61 operational stations with a strength of 180 men.[4]

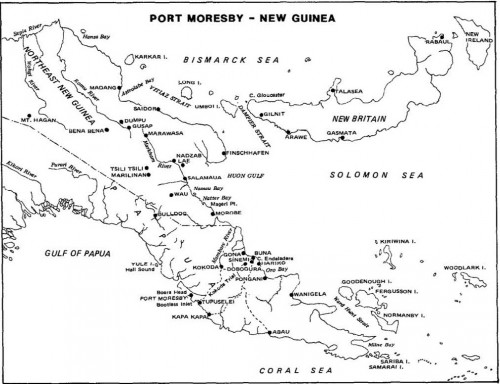

The NGAWW at its peak in late 1944 included more than 150 spotter stations deployed on islands and mainland territories throughout Papua, New Guinea and Dutch New Guinea. To support this expanded network the company’s headquarters had moved to Nadzab in June 1944, (See map below) by which time stations had been established as far as Hollandia. [5]

Many NGAWW company air warning ground observer stations operated behind Japanese lines watching air bases. Thus they were at risk of being captured by the Japanese due to the nature of their operations. These stations were minimally armed– one Owen sub-machine gun for the lead NCO and a rifle for enlisted observers — and lived off what they could pack in or obtain locally after travelling by foot for up to six weeks. A number of the air warning outstations operating near Japanese air bases were over-run and the men manning them killed.

THE POLITICS & LOGISTICS OF THE HOLLANDIA LANDING

In 1944 Australian ground forces captured a Imperial Japanese Army code book code. General MacArthur used this break in reading the previously unreadable mainline Japanese Army code to launch Operation Reckless, the invasion of Hollandia in then Dutch New Guinea. [6]

This operation on New Guinea’s north coast ran into several logistical and political issues between the Australian Labour government of Prime Minister John Curtin and the US military. [7] Hollandia was in Dutch New Guinea and more than two days air travel from Southern Australia. Effectively MacArthur’s forces at Hollandia would be closer to American forward bases in Admiral Nimitz’s Central Pacific theater than Australia. In addition, PM Curtin had made political promises to the Australian people that only Australian Imperial Forces (AIF) would serve outside Australia and Papua New Guinea. The NGAWW company was on the wrong side of that organizational line. So in September 1944 the Australian military refused MacArthur’s requests for the unit to serve outside the Australian area of operations.

DISAPPEARING GROUND OBSERVERS IN US NEW GUINEA HISTORIES

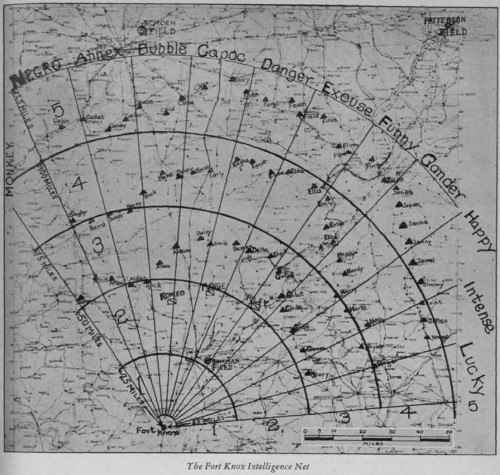

While the Australian air warning ground observers faded from MacArthur’s order of battle. The US Army’s Signal Aircraft Warning Battalions maintained the mission with a company of ground observers assigned to every “lightweight radar SAW battalion” in the theater.[8] These signal air warning ground observer company units owed their existence to then Captain Claire Chennault’s 1933 Ft. Knox air Defense Observer Network that so embarrassed the “Bomber Mafia”. [9]

The success of both the General Chennault’s and General MacArthur’s radio air warning ground observers in China, New Guinea and especially in Leyte in the Philippines was ruthlessly purged from the USAF institutional histories. General H.H. Hap Arnold set the tone for future USAF historians. This is how he put it in his autobiography, Global Mission:

“General Chennault, by his long years of experience with the Chinese, and his uncanny sense of anticipating what the japs would probably do, was able to adopt formations and techniques for the Tenth Air Force which could not be used in any other theater.”[10]

As the Australian New Guinea Air Warning Wireless Company (NGAWW). American SAW companies and RAF wireless observer companies showed. This was far from the case, but General Arnold’s anti-Chennault institutional narrative must be repeated, whatever it’s truth.

And now you know why another of General Douglas MacArthur’s military institutions was forgotten.

-End-

Sources and Notes:

[1] See respectively:

New Guinea Air Warning Wireless

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Guinea_Air_Warning_Wireless

The Coastwatchers 19411945

https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/history/conflicts/australia-and-second-world-war/resources/coastwatchers-19411945

A small Australian army signals unit, the New Guinea Air Warning Wireless Company (NGAWW), also existed as a single entity between February 1942 and 1945. In October 1942, the unit was officially renamed ‘New Guinea Air Warning Wireless (Independent) Company’ as part of New Guinea Force and later, as part of the Corps of Signals in October 1943. These Army ‘spotters’ served in the valleys, highlands and around the coastline of New Guinea and nearby islands as signallers. All members of the unit were volunteers and their unit colour patch was a double diamond, being the ‘independent’ unit (later ‘commando’) insignia. By 1943-1944, the NGAWW had 75 outposts in New Guinea and surrounding islands in the South-West Pacific Theatre of Operations. The unit was disbanded in 1945 and its members have been commemorated with a plaque in the grounds of the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

ROYAL AIR FORCE OPERATIONS IN THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA, 1939-1943

https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205208912

[2] VK2DYM’S MILITARY RADIO AND RADAR INFORMATION SITE.

THE 3BZ COAST WATCHERS WIRELESS SET.

http://www.qsl.net/vk2dym/radio/3BZa.htm

[3], [4], [5] Ibid opening paragraph of the Wikipedia article in note [1]

[6] See the following for Ultra code breaking and “Reckless” operational considerations:

Pages 104 – 115 of Edward J. Drea, MacArthur’s ULTRA: Codebreaking and the War against Japan, 1942-1945 (Modern War Studies) University Press of Kansas; Fourth Edition edition (December 20, 1991), ISBN-10: 0700605762, ISBN-13: 978-0700605767

Battle of Hollandia

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Hollandia

[7] Curtin Government

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curtin_Government

[8] See the following on SWPA SAW Battalions:

Braxton Eisel, “Signal Aircraft Warning Battalions in the South West Pacific in Workd War II, Pages 14 – 24, AIR POWER History, Fall 2004

No author “The SAW Battalions: Their Pacific Record,” Radar No. 11, Pages 26 – 28, 01 October 1945, Office of Air Communications Officer, USAAF

[9] History Friday: Claire Lee Chennault — SECRET AGENT MAN!

Trent Telenko on December 20th, 2013

https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/40740.html

[10] Page 376, General H. H. “Hap” Arnold “Global Mission” Tannenberg Publishing (January 18, 2016) ASIN: B01AYP67E8

https://www.amazon.com/Global-Mission-General-Hap-Arnold-ebook/dp/B01AYP67E8

A little off topic but I am reading a biography of Wendell Fertig, who led a guerrilla force in the Philippines that was very reluctantly aided by McA and who, in 1944, met American troops landing in Mindanao with 30,000 uniformed troops who had basically defeated the Japanese.

He was never promoted by McA and but a revered figure at the Special Warfare school for having led so many foreign troops in combat.

I never figured out why McA was hostile to him a d so reluctant to send supplies.

Commander Eric Feldt, RAN,

I have a copy of Feldt’s book.

I suppose one must allow for the existence of legitimate concern to advance a narrative which defends someone’s convictions that a particular paradigm does a better job than other paradigms. Ie, I gotta give some credence to guys like Arnold believing their understanding best accomplishes the terrible tasks of war, most effectively advances the U.S cause, and most likely saves lives, especially American servicemen, but also even those of enemies.

And I must make allowances for the limitations of leaders not knowing what I know with hindsight. Command involves awful decisions I’m thankful I have not had to face. The issue of mission vs men does not have trivial resolution.

Nonetheless I’m both grieved and disgusted when I learn bits of history that uncover how much some leaders opposed others–on their own side–for what turns out to perhaps primarily depend on self-aggrandizement or personal profit.

Command involves awful decisions I’m thankful I have not had to face.

Curtis LeMay changed the entire strategy of the B 29 force that was the XXI Air Force.

The B 29 was designed as a high altitude bomber and had a pressurized cabin for that purpose. It could fly to 40,000 feet.

However, the Air Force was unaware of the Jet Stream and the accuracy and performance was far below intended.

LeMay arrived and threw the high altitude precision bombing plan out the window.

The B 29s went in at low altitude and firebombed.

They took a lot of damage and that is why Iwo Jima was needed. It was also a fighter base.

In re Fertig – perhaps McA was a wee bit jealous of anyone daring to steal his thunder?

Honestly, I don’t get a very good vibe from reading about McA in the Philippines, or how he was caught again at the start of the Korean War.

There was a book that I reviewed a couple of months ago, about “Pappy” Gunn, https://www.amazon.com/Indestructible-Rescue-Mission-Changed-Course/dp/0316339407/ref=pd_sim_14_1?_encoding=UTF8&pd_rd_i=0316339407&pd_rd_r=cb1247d1-a403-11e8-a008-17cbddca9dad&pd_rd_w=j0xcU&pd_rd_wg=f3ZDT&pf_rd_i=desktop-dp-sims&pf_rd_m=ATVPDKIKX0DER&pf_rd_p=a180fdfb-b54e-4904-85ba-d852197d6c09&pf_rd_r=EGTC2A8BWQQ7X9NN3KD9&pf_rd_s=desktop-dp-sims&pf_rd_t=40701&psc=1&refRID=EGTC2A8BWQQ7X9NN3KD9

He was an early flier, and military retiree, caught as a civilian manager in the PI at the start of the war. From the book, he seems to have been PO’d as hell over how the defense of the PI caved. And he got sidelined, flying various important people to safety, while his own wife and family got left behind, to be interned by the Japanese. I gave it a five-star review on Amazon. It would make an amazing movie.

There is a similar story about guy named Wilson who joined Fertig but whose wife and kids were interned,

Yeh, Mike. Your LeMay summary personalizes one of perhaps a score or two other similar stories I think about when considering significant decisions regarding paradigms of war. Many of these decisions required power struggles I can barely imagine. Ponder, for example, what you know but your brief sketch “threw the high altitude precision bombing plan out the window” leaves out for the uninitiate. That plan had more invested in it (money, lives, people hours of work) than the Manhattan Project. Perhaps more than any single plan of WWII–or of any wars preceding. And LeMay challenged that. And got his way.

What I had in mind was other parts of such stories. The lives lost because of internal politics, because of the absurd stupidities of interservice rivalry, because of business decisions. I’m thinking of B-29s turning into infernos because squabbling over patent rights meant that for not weeks but perhaps years they had to use magnesium carburetors which a backfire would ignite and which, when ignited, could not be put out. This not only killed test crews, not only killed even combat crews, but served to delay development almost enough to make a serious difference in deployment. I’m thinking of American tanks vs German tanks, where American engineers knew the techniques for hardening the turret used by the Germans, yet the command decision was to not decrease production quantity by lengthening production time but instead out produce the Germans–and with the sacrifice of American tankers win by attrition.

Roy, have you read Cooper’s book, “Deathtraps”?

I have seen people disputing his story but it is a fact (I think) that armored divisions in Euroep had a 600% casualty rate.

Cooper’s book is very thoroughly discredited at this point. It’s not so much that he fabricated things as that he had a very narrow window on affairs and extrapolated incorrectly.

American tankers actually took incredibly light casualties, proportionally. Out of 936,259 total casualties for the US Army in WWII, the Armored Force suffered only 6,827, of whom 1,398 were KIA (total dead, including those injured who later died of their wounds, numbered 1,518). The infantry suffered 627,521 casualties, with 110,639 KIA, for comparison – more than 100X more.

The vast majority of the dead and injured tankers were from combat in the ETO. In the entire Mediterranean Theater, from Torch to the end of the war, only 73 American tankers were KIA. 97 tankers were KIA in the Pacific.

The above numbers are drawn from the authoritative postwar report of Office of the Adjutant General, “ARMY BATTLE CASUALTIES AND NONBATTLE DEATHS IN WWII.” It’s easily available via Google search so I’m not going to link it lest this post fall into moderation.

Speaking in more technical terms, the M4’s reputation as particularly vulnerable is largely unearned. Their armor and firepower were comparable to that of the vast, vast majority of the vehicles they faced (as the casualty numbers show) and their mobility was often superior. They were comfortable for the crew and had well-designed optics that gave the commander and gunner a high probability of getting off the first shot, which as postwar analyses showed outweighed all but the greatest disparities in mechanical characteristics. They were just the right size to be easily shipped. They were, perhaps most importantly, very easy to escape if knocked out. That kept crews alive so that they could learn from experience and come home after the war.

Sorry, bit of mental math fail there in my comment. Should read “almost 100X more.”

Cooper’s book was about Normandy. I don’t think the M4 was outgunned in Africa and certainly not in the Pacific.

He may well have had tunnel vision but a friend of mine had a story about tunnel vision in Normandy.

He was a neurosurgeon and was very busy in Normandy at the field hospital where he was the neurosurgeon. He kept getting busier and busier. He finally went to the hospital chief and said he had to have another neurosurgeon.

The chief said none fo the other field hospitals were that busy with head injuries.

He checked around and found out that the ambulance drivers used to watch him operate. He worked in a tent OR and had the wall rolled up to stay cooler. They had chairs and boxes to sit on and watch him through the mosquito net. . After he figured that out, he rolled down the tent wall. They were driving miles out of the way to bring all head injuries to him.

Maybe Cooper was just in the thick of it.

Trent,

Though your points on beaurocratic warfare are well supported, I wonder if there was another reason for Arnold to be circumspect about the China spotter network. A lot of that spotter network overlapped with OSS – see John Birch – and I suspect that at least some of those same people made the transfer to CIA’s payroll, even if they’d since fled to Taiwan and Burma.

This sparks other questions – you mentioned in a previous piece that the Panay was running captured Japanese airplane parts to the P.I. when the Japanese sank. I’ve read elsewhere (Pearl Harbor: Final Judgement by Clauson) that MacArthur complained that he’d had to “barter like an Arab rug merchant” for intelligence – did he have links to Chennault still while SWPA commander? Did Mac get along with Stillwell at all?

>>did he have links to Chennault still while SWPA commander?

Chennault’s 14th AF intelligence was talking to General Kenney’s 5th and later FEAF intelligence during the war.

MacArthur was sending tires salvaged from crashed USAAF P-40’s in the Philippines to Chennault’s Flying Tigers mercenary unit before Pearl Harbor on Chinese air liners.

In exchange for what is unknown, but intelligence on the Japanese was likely the coin of the realm in this highly illegal under US law transaction.

Mike K,

Nicholas Moran has a couple of you tube videos on the Sherman you should watch.

See this one:

Myths of American Armor. TankFest Northwest 2015

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bNjp_4jY8pY

And particularly this one:

US AFV Development in WW2, or, “Why the Sherman was what it was”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TwIlrAosYiM

Specific points to review in the above video are:

Sherman Roof mounted site

https://youtu.be/TwIlrAosYiM?t=3751

and this:

Death rate inside a Sherman.

https://youtu.be/TwIlrAosYiM?t=3798

Directrix and Trent re Shermans and tank armor:

Years ago a friend, knowing that I know something about metallurgy and a little about WWII, asked me how come people thought the Tiger v Sherman comparison left the Sherman short. I did not know. But, provided one is skeptical and somewhat aware already, the internet is one’s friend

As you two noted in your comments above, all-in-all the Sherman actually did fairly well. Your comments condense a lot of research into a reasonably complete short summary. The links you provided, Trent, provide cases in point, listing the strengths of the Sherman while pointing out its intention included much more than antitank assualt and also noting some of the failures of the Tiger. Much shortened version of that short summary: the Sherman had many tasks besides the relatively infrequent confronting of Tigers, and did these very well. It did not quickly break down, had good optics making for more accurate shots, was easy for the crew to escape when hit, was more mobile than other tanks, was tough enough to withstand anything less than fairly robust antitank weapons. Meanwhile, the Tiger suffered major maintenance headaches, was less mobile than the Sherman. Not only that, but (something the links did not note) the Tiger was many multiples of times more expensive to build than the Sherman. (Yes, this is part of the point I made about the decision to simply out produce the German.)

However, none of that addresses what I pointed out in my comment which energized the ‘tank thread’. American decision makers knew the same stuff the Germans did and could have made the Sherman much better. They knew it because not only did American engineers know it, but because the knowledge is common in nearly any given metal shop.

Somewhat over condensed version–Germans made their armor much stronger by two means: alloying with molybdenum and quenching. (They did not have access to molybdenum throughout the war. They captured mines during the course of the war. This lead to their armor going from fairly poor to very tough. Then, in the latter part of the war, American bombers destroyed the mine facilities. This joined a number of factors significantly decreasing the quality of German armor.) Molybenum made the metal tough, able to take abuse without breaking. Heat treating, annealing, and then quenching made it hard, much more resistant to abuse. (Think about flexing a strip of metal. The tougher the metal, the more it will not only resist being bent, but take being bent without it fracturing. Now think what would happen if you were to try to flex a piece of ceramic the same thickness, say that of a fine china plate””my wife does not like this illustration. The plate would prove much more resistant to being bent. But given enough bending force, the plate would not bend, probably not even merely crack, but shatter. Brittle, with shatter failure, is the trade off to making a metal hard.)

Americans could have made the Sherman much more able to survive the confrontation with the Tiger or other antitank weapons, much more likely to save American soldiers. Americans had access to molybdenum, knew how to quench harden. But these steps would have both driven up expense (a lot) and slowed production. For those (never acknowledged, as far as I know) reasons and, probably, others, the deciders chose to do as the Russians did with the T-34 and the Japanese with the Zero: overwhelm the enemy by sending lots of soldiers. (Recall re the Zero: it was agile because it was light from having little armor and missing many braces in its frame, and had to weigh little because Japan did not have access to metals that would have enabled building a far more robust engine, all of which meant the Zero could not survive much punishment.)

I maintain the point of my originating comment: many command decisions grieve me because I see that soldiers had too little value in those decisions.

Something that I think is worth noting –

Soviet Tank Ace Dmitry Loza wrote a memoir of some of his experiences during the war (you should be able to find a free to read copy of it online with an internet search). While I believe he started out in a T-34, he spent most of the war in an M4A2 Sherman. He briefly touched on the issue of safety, and wrote that he felt that the Sherman was a safer vehicle for the crew than the Soviet T-34.

I thought that was interesting and worth noting given the discussion above.

He also liked the Sherman for other reasons – namely, the crew comforts were much greater. Soviet tanks were much more spartan. And newly arrived American tanks had a note that included the signature of one of the members of the assembly line crew, and basically read (paraphrasing), “I helped build this tank, and stand behind the quality of it.” He felt that a person who would include a note like that in the vehicle that they were building was the kind of person who would take pride in building it properly.

The highest production M4 Sherman year was 1943 and that was before the 76mm gun and 2nd generation Sherman hulls appeared.

In addition it took 150 to 189 days for a Sherman to leave a factory to when it showed up on the battlefield. For the Germans the time from factory to front was more like a week to a month. Effectively, Shermans were fighting tanks from their design future.

The following is a 2008 post from the Axis History Forum regards Sherman tank production in WW2 —

=============

Dear me, didn’t we just go over this? :D Maybe I’ll give you the short answer?

Total Production:

M4 with 75mm 33,671

M4 with 76mm 10,883

M4 with 105mm 4,680

Total M4 49,234

Lend-Lease M4 shipped:

To the British Empire

With 75mm 15,256

With 76mm 1,335

With 105mm 593

Total 17,184

To Canada (not included above)

With 75mm 4

To France

With 75mm 755

To USSR

With 75mm 2,007

With 76mm 2,095

Total 4,102

To American Republics

With 75mm 53

Total Lend-Lease 22,098

Known US losses were:

Total Losses 12th AG to 12 May 1945 was 3,255

Total Losses 15th AG to 14 September 1944 was 588

Partial Losses 6th AG 15 August – 1 May 1945 was 295

Total Losses II Corps, Tunisia, 15 March-9 May 1943 was 60

Total Losses Seventh Army, Sicily was 8

Total Losses 1st AD, Tunisia, 14-21 February 1943 was 94

Total Known US Losses 4,300

Rebuilt and training tanks in the US 6,874-2,145 Lend-Leased (included above) = 4,729

Actual on hand and unit requirements were:

Total on hand with units of 12th AG as of 5 May 1945 was circa 3,738

Total T/E 12th AG as of 30 April 1945 was 4,184

Total on hand with units Seventh Army as of 30 April 1945 was 996

Total T/E Seventh Army as of 30 April 1945 was 1,029

Total T/E 15th AG as of 1 May 1945 was 561

Total T/E PTO as of 1 May 1945 was 789

Total T/E CONUS and en route was 240

Total on hand with units was circa 6,324

Total T/E with units was 6,731

US Army reserve requirments totaled roughly 2,309

Total conversions to other types (M35, TRV, etc) was 3,610

So 49,234-22,098-4,300-4,729- ~6,500- ~2,309-3,610 = 5,688 unaccounted for as of circa 1 September 1945.

Part of that is uncounted losses and USMC strengths in the Pacific, I simply don’t have a whole lot of data for those, but perhaps 1,000 is a fair estimate? That leaves about 4,600-odd, which actually isn’t very many as these things go.

Consider that the 1st QTR 1945 production was 4,076 and 2nd QTR 1945 was 2,687, ending the run and that, like the 4,729 rebuilt ones that weren’t Lend-Leased, most of those may never have left CONUS (reportedly in February 1945 there were about 7,000 still in the US)?

Certainly at the end of the war large numbers were put into reserve in protective containers for possible later use.

1) Deathtraps. Why does someone on the internet CONSTANTLY bring this book up? Its been discredited – and doesn’t say anything new.

2) “MacA was reluctant to send supplies” – I don’t know what that means. Prior to the Leyte invasion the only way to send supplies to the Philippines was by Sub. And the Navy controlled the Subs, not MacArthur. IRC, the Navy was only willing to use two obsolete subs and the occasional fleet sub for Philippine supply missions.

It could be, guerrilla units on Luzon or Leyte were given priority because those islands were more important. Mindinero was a lesser importance, and was not invaded till April 1945.

I did a blog post about the Sherman tank design and why I thought that the US ordnance dept. did what they did.

https://theartsmechanical.wordpress.com/2015/07/24/was-the-us-army-really-stupid-during-ww2/

The post was done before Nick Moran’s second Sherman video, but nothing that he did invalidates the post. Now as to why the US didn’t heat treat or use moly steels in the turret armor. I think that the big u=issue was that throughout the war and for a long period after the war US tank turrets were cast steel. That creates some problems when using a Moly steel because Moly steels have a higher melting point and you would have to take that into account in the foundry something that is not easy to do when you are under significant production pressures. As for heat treating, castings have to be carefully designed to avoid stress cracking. At the beginning of WW2 the US had just begun to be able to manufacture large steel castings without having a real problem with stress cracking without heat treating. Germany had to fabricate their turrets because the German railroad industry hadn’t developed the ability to cast the large components like the US industry had. Look closely at German and US locomotive from the mid 1930’s and see how many components are cast rather than fabricated. Just before the war, the US railroad industry was casting locomotive frame and I’m fairly sure that nobody else was. See the PRR GG1 as an example and compare it to similar electric locomotives from the same period in Europe.

Fabricating a turret from rolled plates was expensive and heat treating and using more expensive steels just added to that cost and gave you a weaker, not stronger turret in the end. There are significant advantages to large steel castings.

Also, John Parshall has a good look at how the US and the Soviets built tanks as opposed as to how those Tigers were produced.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N6xLMUifbxQ&t=3021s

One thing to note, no tank armor on any tank could stop the round from an 88mm gun. ON the other hand, the 88 mm is a large gun to haul around. So you have all the problems that go with such a large gun, especially when you have to tow it.

As for the Tiger, from what I’ve seen, it’s actual performance in combat wasn’t much different than the Sherman’s in the role that a tank is supposed used for, offensive combat.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YM31hcc31QE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4_bJpeQ7bOU

King Tigers were knocked out and defeated just as a Sherman would be. The difference is that the loss of a Tiger represented a far larger cost than a loss of a Sherman.

Jccarlton,

US tank armor that was rolled and cast prior to mid-to-late 1943 was of very spotty quality, particularly with thicker castings.

The issue was caused by the lack of effective US Army Ordnance QC of American tank armor in 1942-1943 time period caused by multiple factors including;

1. A the lack of a trained inspectors,

2. _MANY_ new armor vendors with large production volumes, and

3. The delayed use of radiographic NDI inspection techniques until 1943.

This is covered in the book:

World War II ballistics : Armor and Gunnery – 2001

by Lorrin Rexford Bird, Robert D. Livingston

A copy of it is located on scribd here —

https://www.scribd.com/doc/219173969/WWII-Ballistics-Armor-and-Gunnery#user-util-view-profile

Pages 8-9 have a thumbnail history of American tank armor in WW2.

Pages 10-14 cover the other major tank producing powers minus Japan.

Google has a lot of images from the book here:

https://www.google.com/search?q=WWII+Ballistics+–+Armor+and+Gunnery&num=100&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj9i6q1t5rdAhUM7IMKHWHlB28QsAR6BAgGEAE&biw=1920&bih=912

Roy Kerns said —

>>Americans could have made the Sherman much more able to survive the confrontation with the Tiger or other antitank weapons, much more likely to save American soldiers. Americans had access to molybdenum, knew how to quench harden. But these steps would have both driven up expense (a lot) and slowed production.

The issue here is US Army Ordnance didn’t know what it didn’t know.

Every major power had a learning curve as pre-war they shot their projectiles at their own armor and not the enemy’s.

An example pf this is that early German 88mm APHE projectiles failed versus the KV-1 when it they faced much harder sloped armor than their projectiles were designed to defeat.

Only after hard combat experience did the experience of your projectiles versus enemy armor and enemy projectiles versus your own armor get through the bureaucracy. This generally took 12 to 18 months in WW2.

This was roughly the late Tunisian campaign for US Army Ordnance.

That was roughly when US Army Ordnance’s QC program caught up with it’s armor production in terms of eliminating protection flaws.

People constantly focus in on tank vs. tank warfare.

The biggest killers of Sherman tanks in WW2, were mines, Anti-tank guns, artillery and panzerfausts.

At anytime on the Western Front (Sept 44 onwards) you probably and 5000+ Allied Shermans and 500 Tigers.

Mechanical reliability and numbers are better than quality, at a certain point.

People do the same thing with fighters in WW2. The P-47 was an inferior dogfighter under 20,000 to the ME109. But the P-47 could carry more bombs than a Stuka, escort B-17s, and was a superior bomber destroyer. And could take damage that would send a Me-109 to the graveyard.

Trent, I am watching the video of “Chieftan.”

He recommends “Deathtraps.” He does say it is a “Memoir,” not history and I agree.

The things you find. I had seen it mentioned that the network that guided the fighters in the Battle of Britain did not rely on the Chain Home radar, but on ground based observers like Chenault did. Turns out that was indeed the case. Here is a pathe film of the observers in action.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DQWWmwrDFzU

And a website.

http://www.roc-heritage.co.uk/

This —

http://www.roc-heritage.co.uk/

is a very well developed site on UK ground observers. And in particular see the RAF operations center documents here:

http://www.roc-heritage.co.uk/operation-centres.html