She was born to privilege and a degree of wealth, at the turn of the last century Muriel Morris, an heiress of the Swift meatpacking fortune, and by most accounts conflicted over that circumstance. Like a scattering of her peers in the debutant world, she had an interest in social justice, as it was generally understood at the time. She is reported to have read Upton Sinclair’s polemic The Jungle as a teenager and been horrified doubly so as both sides of her family had made their fortunes in the industry which Sinclair portrayed as especially brutal and gruesome. Muriel Morris was also of an unexpectedly intellectual bent and determined enough to pursue her intellectual interests first with studies at Oxford, England in the 1920s, and then in of all places, Vienna, Austria, where she hoped to study psychoanalysis with Sigmund Freud. She briefly married a British artist, Julian Gardiner, by whom she had a single child, a daughter, before deciding to pursue a medical degree at the University of Vienna in 1926. She had a trust fund sufficiently generous to support herself and her small daughter.

Book Notes

Koonin Offers a Check on “The Scienceâ€

I ordered Steven Koonin’s Unsettled? more out of perversity than honest curiosity. It was a vote for a skeptic, for a man labelled a “denier” and thus worthy of canceling. I was wrong on several counts: it is holding on Amazon with a fairly high rating, and, I was able to get something out of it. He clearly wants to reach people like me, bewildered by charts and graphs. The tables are there, but his style and analogies accessible. (Which means it is dumbed down, but I appreciate his desire for a larger audience.) He has some of the commonsense of Lomborg: practical, prioritizing what is certain, seldom emphasizing the “wrong” and more often the imprecise, the unknown. Some reviewers found him full of himself, but his voice is that of a close reader, looking at the body of reports, comparing assertions and data with the summaries and interpretations. I assume his readings are honest and he is a good physicist but what do I know.

What struck me were the assumptions of a method he promotes, one other disciplines use and he sees as appropriate. In Chapter 11, “Fixing the Broken Science,” he suggests major reports on climate would benefit from being “Red Teamed.” The “Red Team” critiques it, “trying to identify and evaluate its weak spots,” “a qualified adversarial group would be asked ‘What’s wrong with this argument?’” Then the authors, the “Blue Team” rebuts, seeking more information, firming up arguments, gaining precision. He looks at examples where a report’s data did not support the conclusions or summaries (sometimes leading to popular articles with further overstatements). Perhaps the authors had more data, perhaps the summaries were written by those holding too strong an opinion to let the results stand on their own. Perhaps. . . But, of course, if conclusions don’t match research, that’s important.

Traditionally, peer review even in the humanities is designed to note such problems, but these have been less and less rigorous as more subjective definitions of “truth” evolve (or perhaps of careerism). More importantly, “The Science” (climate consensus) is not limited to the ivory tower; it influences awards of positions, grants, research. And, it affects policy. Seeing “The Science” as “settled” tempts those doing “science.”

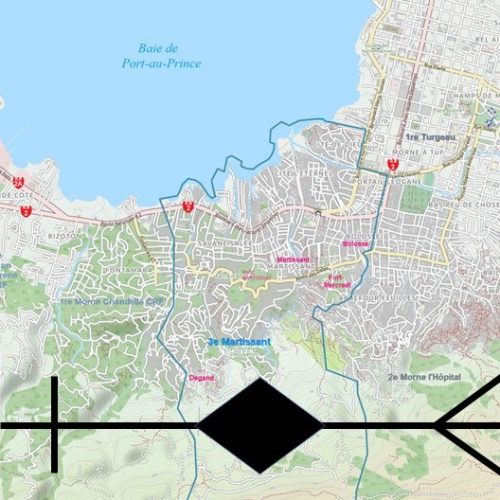

Dilèm Aksyon Kolektif nan Matisan

Generatim discite cultus

(Learn the culture proper to each after its kind)

— Virgil, Georgics II

Stephen Biddle, Nonstate Warfare: the Military Methods of Guerrillas, Warlords, and Militias (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021)

By way of making this more than a merely armchair review, I will be discussing the developing situation of state failure in Haiti, which is providing a personally harrowing example of the phenomena theorized and studied in this book. NB: additional situation reports like the one I quote from below will appear at this OCHA webpage.

I. Increasingly Scale-Free Military Activity in the 21st Century

In this follow-up to 2004’s Military Power: Explaining Victory and Defeat in Modern Battle (also from Princeton), Stephen Biddle continues to elucidate the many ramifications of the one-to-many relationship which came to dominate the battlefield between the Napoleonic Wars and World War I. Over that century and in the decades that followed, individual-service weapons increased in rate of fire from a (very) few rounds per minute to ~10 rounds per second, in effective range from ~100 to >300 meters, and in accuracy from (optimistically) 10 to 1.5 milliradians. Say 2 ½ orders of magnitude improvement in RoF, half an order of magnitude in range, and one order of magnitude in accuracy; multiplying these together to create a sort of index of effectiveness, I get an overall change of 4 orders of magnitude, with stark implications for battlefield environments.

Xi and Me

It turns out that Xi Jinping and I have something in common: we are both fans of Goethe’s Faust. Indeed, Xi is said to even know the work by heart.

I wonder what aspects of Faust have been particularly meaningful to Xi, both personally and as relates to his current job as Dictator. Here’s the passage that immediately came to my mind on learning of Xi’s Faust-affinity…

As a reward for services rendered, the Emperor grants Faust a narrow strip of land on the edge of the sea, which Faust intends to turn into a new and enlightened society by reclaiming land from the sea…along the lines of the way that Holland was created, but in a much more intensive manner. Faust’s land-reclamation project goes forward on a very large scale, and is strictly organized on what we would now call Taylorist principles:

Up, workmen, man for man, arise anew!

Let blithely savor what I boldly drew

Seize spade and shovel, each take up his tool!

Fulfill at once what was marked off by rule

Attendance prompt to orders wise

Achieves the most alluring prize

To bring to fruit the most exalted plans

One mind is ample for a thousand hands

Faust’s great plan, though, is spoiled (as he sees it) by an old couple, Philemon and Baucis, who have lived there from time out of mind. “They have a little cottage on the dunes, a chapel with a little bell, a garden full of linden trees. They offer aid and hospitality to shipwrecked sailors and wanderers. Over the years they have become beloved as the one source of life and joy in this wretched land.”

And they will not sell their property, no matter what they are offered. This infuriates Faust…maybe there are practical reasons why he needs this tiny piece of land, but more likely, he simply cannot stand having the development take shape in any form other than precisely the one he has envisaged. Critic Marshall Berman suggests that there is another reason why Faust so badly wants Philemon and Baucis gone: “a collective, impersonal drive that seems to be endemic to modernization: the drive to create a homogeneous environment, a totally modernized space, in which the look and feel of the old world have disappeared without a trace…”

Faust directs Mephisto to solve the problem of the old couple, which task Mephisto assigns to the Three Mighty Men… who resolve the issue by the simple expedient of murdering the pair and burning down their house.

Faust is horrified, or at least says that he is:

So you have turned deaf ears to me

I meant exchange, not robbery

This thoughtless, violent affair

My curse on it, for you to share!

To which the Chorus replies:

That ancient truth we will recite

Give way to force, for might is right

And would you boldly offer strife?

The risk your house, estateand life.

Xi seems resolved to ensure that the ancient pattern recited by the Chorus will be the one that rules in China. And there are plenty of influential people in America who reject progress we made in evolving beyond this ancient and brutal pattern..by building a wall consisting of free speech, due process of law, separation of powers, and a written constitution, and fighting to defend that wall. Such people evidently want to demolish the wall and let the ancient pattern be firmly emplaced here as well…apparently under the assumption that they will be the ones who ultimately direct the Mighty Men.

See Claudia Rosett’s related post: Xi Jinping’s Tianamen Vision is Coming for Us All.

My review of Faust is here.

Ferdinand and Hermann’s Excellent Frontier Adventure

(As promised during the Zoom meet-up this afternoon, the absolutely true story of the first cataract surgery in Texas.)

The practice of medicine in these United States for most of the 19th century was a pretty hit or miss proposition. Such was the truly dreadful state of affairs generally when it came to medicine in most places and in all but the last quarter of the 19th century that patients may have been better off having a go with the D-I-Y approach. Doctors trained as apprentices to a doctor with a current practice or studied some books and hung out a shingle. Successful surgeons possessed two basic skill sets; speed and a couple of strong assistants to hold the patient down, until he was done cutting and stitching.

But in South Texas from 1850 on, there was doctor-surgeon who became a legend, for his skill, advanced ideas, and willingness to go to any patient, anywhere and operate under any conditions and most usually with a great deal of success. Doctor Ferdinand Ludwig von Herff, who dropped the aristocratic ‘von’ almost immediately upon arriving in Texas, was also an idealist, and prepared to live in accordance with his publicly espoused principles. He came to Texas in 1847 as part of a circle of young men called the “Forty,” who had a plan to establish a utopian commune along ideas fashionable at the time.