Sometime around the middle of the time my daughter and I lived in Athens, the Greek television network broadcast the whole series of Jewel in the Crown, and like public broadcasting in many places— strictly rationing their available funds— they did as they usually did with many worthy imported programs. Which is to say, not dubbed into Greek— which was expensive and time-consuming— but with Greek subtitles merely supered over the scenes. My English neighbor, Kyria Penny and I very much wanted to watch this miniseries, which had been played up in the English and American entertainment media, and so she gave me a standing invitation to come over to hers and Georgios’s apartment every Tuesday evening, so we could all watch it, and extract the maximum enjoyment thereby. We could perhaps also make headway with our explanation to Kyrie Georgios on why Sergeant Perron was a gentleman, although an enlisted man, but Colonel Merrick emphatically was not.

Lit Crit

Pushing Back Against Branding Bureaucratese

A thoughtful and well-written piece from COMJAM: Dear Admiral…

The applicability of these thoughts is not limited to the Navy.

Bureaucratic language and the bureaucratic mindset are not the friends of the true marketing imagination.

Natty Bumppo Would Understand

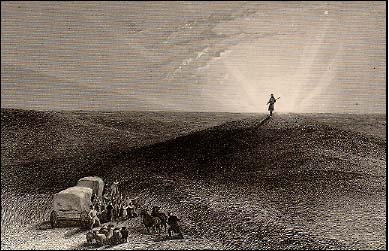

Tea Partiers want to be left alone government kept from faith and speech, guns and books. Government restrained from taking property house or wallet. Anyone who thinks those beliefs don’t have legs isn’t getting my phone calls the tea party candidate’s supporters in the primary fill the answering machine and from my husband’s relatives fill our in-box. It has legs because this is who we are, or at least want to be: responsible adults, autonomous. Equivalence with the Occupiers misses core differences; Occupiers want what they fantasize the 1% have. We are human we covet. But Americans haven’t taken to OWS because we aren’t proud of our envy; we prefer grandeur to pettiness.

The Tea Party has roots – aware that restraint of power is difficult, but has a proud American history. Washington’s greatness lay not only in his victories but also his restraint he refused (as few have) to abuse his power restraint gained him respect, gave him another kind of power. Respect for flag and country characterizes the tea party; it is respect for a greatness defined by its restraint recognizing the limits of government when it bumps against man’s intrinsic rights.

A Love Like That

In “Those Sexy Puritans,” Edmund Morgan argues “Puritan theology placed a high value on the affections, specifically on the love that Christ excited in believers.” Noting that “the most intense love that most people knew or felt was sexual,” in Puritan sermons, like Taylor’s poetry, the conversion experience was naturally analogized to marriage. Christ was bridegroom, the bride a believer of either sex (24). Morgan further observes that “In giving meaning to religious experience, sexual union in return acquired a religious blessing. It was, of course, conferred only on sex in marriage. Christ was a bridegroom, not a libertine. But marriage without sex was as hollow as religion without the fulfillment of Christ’s union with the soul” (25). Biology, religion and the practical linkage of family all reinforced each other, as a mother’s desire to free her heavy breasts keeps her close to and nurturing her child. The physical isn’t opposed to the spiritual; this is no denigration in Puritan thought. To them, God created natural desires that conform to a greater plan of course, when those desires are willful and alienated, they thwart the plan. Few subscribe to these beliefs now, but entering their world still helps us understand ours.

The Spectacle of Wrecks on the Internet Superhighway

I am not one of those people who thrive on discord which may be one of the reasons that I gave up posting on Open Salon yea these many months ago. I am at heart a rather peaceful and well-mannered person who does not actively seek out confrontation, on the internet or in real life … no really, stop laughing! I merely present myself as someone who doesn’t suffer fools lightly, and who will not hesitate to squash them, which has the pleasing result of not being very much bothered by fools. It’s called ‘presence’… and has worked out pretty well, actually online and in real life. I can easily count the number of fools I have squashed … only a dozen or so that I remember. And none of them came back for seconds.

I don’t deliberately slow down to gawk at epic highway pileups either … except that in real life, everyone ahead of you has slowed down anyway, and the full spectrum of destruction is spread before you. And as for epic internet crackups … one can go for months without being made particularly aware of them, but this week my attention was caught by news of the mother-in-law-of all internet crack-ups to do with books. This one I must pay some attention to, as books are my vocation. It’s a more appalling spectacle than the Great Books And Pals/Jacqueline Howett Review Crackup of 2011, which should have served as an object lesson in how an author should not respond to a mildly critical review. This fresh slice of internet literary hell is what I am dubbing the Great Stop the Goodreads Bullies Cluster of 2012.