There have been literally hundreds of books and thousands of articles on the June 6th 1944 invasion of Normandy. Almost every facet of the invasion has been examined in the last 75 years. Yet for all that, there are simply some subjects related to the Normandy invasion that professional military historians won’t deal with.

There are a lot of reasons for this, but at it’s heart, it is simply the case many, if not most, academic military historians got into history because they didn’t want to do math. When you start talking about bandwidth, frequency, wavelength, quartz crystal radio control, atmospheric transmissiblity, radio ducting, and how all this related to the command, control, communications and intelligence (C3I) systems of the Normandy Invasion. When you bring up all this “Retro-High Technology,” the vast majority run screaming from the subject.

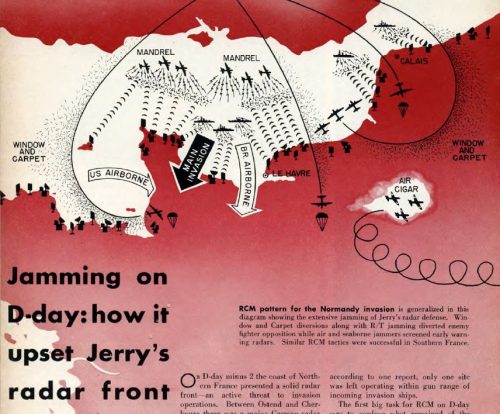

This is a real shame as it has left out the story of how the Allies created a C3I system to control all it’s air and sea forces. Projected this C3I system across the English Channel while destroying/stunning/jamming the German C3I system. And then implanted that C3I system in France. All the while making sure thousands of Allied fighters and anti-aircraft gunners didn’t shoot at each other or down dozens of troop laden transport planes filled with paratroopers or towing gliders, as happened in Operation Husky, the Invasion of Sicily. It simply hasn’t been addressed.

This post is my attempt to fill this gap in the historical record by explaining the problems the Western Allies faced. The Operation’s Neptune and Overlord planning process they used to overcome them with cunning yet simple ideas like invasion stripes, and a broad brush outline of how they executed those plans.

RETRO-HIGH TECH BACKGROUND

World War 2’s “Retro-High Tech” warfare was defined on the ground, in the air and on the sea by the use of electronic signals intelligence (SIGINT) with the addition of RADAR for land or sea based airpower. Both SIGINT and RADAR had to be tied together to an effective radio and wire telecommunications network in order to provide both intelligence services the necessary data for evaluation and the military commanders the processed intelligence to act upon in order to be effective.

The effective use of RADAR required a very rapid gathering, processing, decision making and dissemination of those decisions over a vast geographic area by radio, telegraph and telephone. During World War 2 (WW2) RADAR networks had the addition of first radio direction finding and then “low level” signals intercepts of voice and Morse code in the clear, simple, easy to use, but quickly breakable codes — Organizations doing this were called “Y-Service” by the British — followed eventually by higher level cryptographic code breaking (or “ULTRA”) being added into this network.

This four legged stool of military sensors, communications, intelligence, and decision making by military commanders is normally referred to as Command, Control, Communications and Intelligence or “C3I”. In particular, RADAR played the role of “Keystone Military Technology.” And by “Keystone” I mean an analogy to the biological concept of a “Keystone species” in an ecosystem, not unlike the role of algae in the ocean ecosystem or grass for a prairie ecosystem. This military C3I ecosystem model is far more developed in the 21st century especially with the arrival of digital electronic computers — but it is simply a conceptual embellishment of this 1940’s “Revolution in Military Affairs.”