In his Foundation series of books, Isaac Asimov imagined a science, which he termed psycho-history, that combined elements of psychology, history, economics, and statistics to predict the behaviors of large population over time under a given set of socio-economic conditions. It’s an intriguing idea. And I have no doubt much, much more difficult to do than it sounds, and it doesn’t sound particularly easy to begin with.

In his Foundation series of books, Isaac Asimov imagined a science, which he termed psycho-history, that combined elements of psychology, history, economics, and statistics to predict the behaviors of large population over time under a given set of socio-economic conditions. It’s an intriguing idea. And I have no doubt much, much more difficult to do than it sounds, and it doesn’t sound particularly easy to begin with.

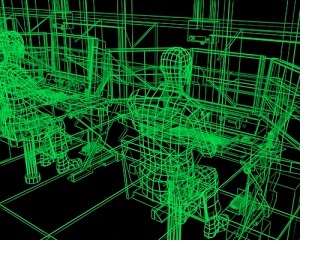

Behavioral modeling is currently being used in many of the science and engineering disciplines. Finite element analysis (FEA), for example, is used to model electromagnetic effects, thermal effects and structural behaviors under varying conditions. The ‘elements’ in FEA are simply building blocks, maybe a tiny cube of aluminum, that are given properties like stiffness, coefficient of thermal expansion, thermal resistivity, electrical resistivity, flexural modulus, tensile strength, mass, etc. Then objects are constructed from these blocks and, under stimulus, they take on macro-scale behaviors as a function of their micro-scale properties. There are a couple of key ideas to keep in mind here, however. The first is that inanimate objects do not exercise free will. The second is that the equations used to derive effects are based on first principles, which is to say basic laws of physics, which are tested and well understood. A similar approach is used for computational fluid dynamics (CFD), which is used to model the atmosphere for weather prediction, the flow of water over a surface for dam design, or the flow of air over an aircraft model. The power of these models lies in the ability of the user to vary both the model and the input stimulus parameters and then observe the effects. That’s assuming you’ve built your model correctly. That’s the crux of it, isn’t it?

I was listening to a lecture on the work of a Swiss team of astrophysicists the other day called the Quantum Origins of Space and Time. They made an interesting prediction based on the modeling they’ve done of the structure of spacetime. In a result sure to disappoint science fiction fans everywhere, they predict that wormholes do not exist. The reason for the prediction is simply that when they allow them to exist at the quantum level, they cannot get a large scale universe to form over time. When they are disallowed, the same models create De Sitter universes like the one we have.

It occurred to me that it would be interesting to have the tools to run models with societies. Given the state of a society X, what is the economic effect of tax policy Y. More to the point, what is cumulative effect of birth rate A, distribution of education levels B, distribution of personal debt C, distribution of state tax rates D, federal debt D, total cost to small business types 1-100 in tax and regulations, etc. This would allow us to test the effects of our current structure of tax, regulation, education and other policies. Setting up the model would be a gargantuan task. You would need to dedicate the resources of an institute level organization with expertise across a wide range of disciplines. Were we to succeed in building even a basic functioning model, its usefulness would be beyond estimation to the larger society.

It’s axiomatic that anything powerful can and will be weaponized. It is also completely predictable that the politically powerful would see this as a tool for achieving their agenda. Simply imagine the software and data sets under the control of a partisan governing body. How might they bias the data to skew the output to a desired state? How might they bias the underlying code? Might an enemy state hack the system with the goal to have you adopt damaging policies, doing the work of social destruction at no expense or risk to them?

Is this achievable? I think yes. All or most of the building blocks exist: computational tools, data, statistical mathematics and economic models. We are in the state we were in with regard to computers in the 1960s, before microprocessors. All the building blocks existed as separate entities, but they had not been integrated in a single working unit at the chip level. What’s needed is the vision, funding and expertise to put it all together. This might be a good project for DARPA.