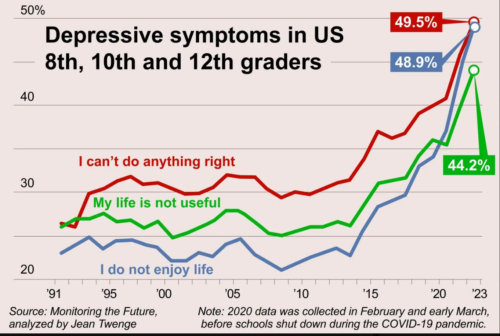

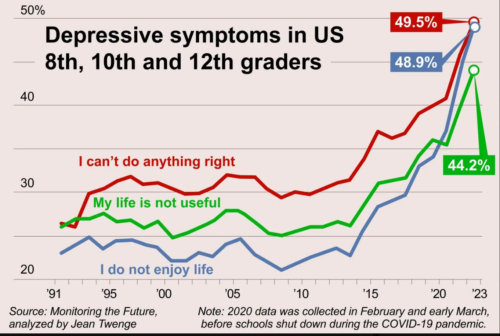

From cdrsalamander at Twitter, based on an analysis of Monitoring the Future survey data by Jean Twenge.

Thoughts?

Some Chicago Boyz know each other from student days at the University of Chicago. Others are Chicago boys in spirit. The blog name is also intended as a good-humored gesture of admiration for distinguished Chicago School economists and fellow travelers.

From cdrsalamander at Twitter, based on an analysis of Monitoring the Future survey data by Jean Twenge.

Thoughts?

New Zealand may adopt a new science curriculum that doesn’t have much actual science in it:

Central concepts in physics are absent. There is no mention of gravity, electromagnetism, thermodynamics, mass or motion. Chemistry is likewise missing in action. There is nothing about atomic structure, the periodic table of the elements, compounds or molecular bonding,” he said of the draft.

Rather than physics, chemistry, and biology, the document proposes teaching science through four contexts that appear to draw from fundamental principles of the United Nation’s Agenda 21: climate change, biodiversity, infectious diseases, and the water, food, and energy nexus.

Sounds a lot like the science curriculum that was proposed in the UK circa 2005:

Instead of learning science, pupils will “learn about the way science and scientists work within society”. They will “develop their ability to relate their understanding of science to their own and others’ decisions about lifestyles”, the QCA said. They will be taught to consider how and why decisions about science and technology are made, including those that raise ethical issues, and about the “social, economic and environmental effects of such decisions”.

They will learn to “question scientific information or ideas” and be taught that “uncertainties in scientific knowledge and ideas change over time”, and “there are some questions that science cannot answer, and some that science cannot address”. Science content of the curriculum will be kept “lite”. Under “energy and electricity”, pupils will be taught that “energy transfers can be measured and their efficiency calculated, which is important in considering the economic costs and environmental effects of energy use”. (The above is from John Clare’s article in the Telegraph.)

According to Melanie Phillips: “The reason given for the change to the science curriculum is to make science ‘relevant to the 21st century’. This is in accordance with the government’s doctrine of ‘personalised learning’, which means that everything that is taught must be ‘relevant’ to the individual child.”

2005 was a long time agoI don’t know whether or not this curriculum is still in place in the UK; I use it as an example because it makes a certain kind of thinking very clear. The class is not really about Science, it is about ‘Society’, and everything that is taught must be ‘relevant’ to the child.

And, closer to home, California has a new math curriculum. While math teaching certainly could use improvement, I don’t have a good feeling about this program…see for example this and this, also these comments.

Also, the curriculum includes “data science” as an alternative to Algebra II…see this critique: “Here’s the issue: the data science course is not a good path to a career in data science…It’s math lite for kids who don’t expect to use much math in life. And that’s fine!…as long as the kids KNOW that’s what they’re signing up for. But it’s not being sold that way — it’s being sold as a way to get more kids into data science. …and that’s misleading.”

An actual San Francisco data analytics guy offers this detailed analysis and critique of the curriculum.

Here’s a post with a rather arresting title from a few days ago at Ricochet: She’s a brilliant teacher, perhaps she should stop. At a BBQ, the writer encountered a teacher from his high school days.

Besides my mother, she is the best teacher I’ve ever had. She taught me Physics and Inorganic Chemistry. And the way she taught — understanding rather than memorization — allowed me to ace science and math classes in college and medical school. She helped me so, so much.

She is now 61 years old and is considering retirement. She moved from my public school to a private school, but it’s still wearing her down. She complains that modern students lack curiosity and motivation, while administration and parents pressure her to just give everyone A’s. She teaches how to understand science and math — but they just want her to stamp her approval on their resume. She’s growing increasingly frustrated, to the point where she doesn’t want to go to work anymore.

This is a different problem from the problems of deliberately-weakened curricula, but the root is the same: the belief that acquisition of knowledge is not what matters, rather, what matters is moving through the system and getting that piece of paper. (And, in the case of many updated curricula, ideological indoctrination is also a key objective)

Andy Kessler of the WSJ describes some conversations he has had with the founder/CEO of the Khan Academy, a nonprofit organization whose mission is “to provide a free, world-class education to anyone, anywhere.”

Three years ago, Sal Khan and I spoke about developing a tool like the Illustrated Primer from Neal Stephenson’s 1995 novel “The Diamond Age: Or, a Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer.” It’s an education tablet, in the author’s words, in which “the pictures moved, and you could ask them questions and get answers.” Adaptive, intuitive, personalized, self-paced—nothing like today’s education. But it’s science-fiction.

Last week I spoke with Mr. Khan, who told me, “Now I think a Primer is within reach within five years. In some ways, we’ve even surpassed some of the elements of the Primer, using characters like George Washington to teach lessons.” What changed? Simple—generative artificial intelligence. Khan Academy has been working with OpenAI’s ChatGPT since before its release last December.

In the novel, the main character Nell asks about ravens, and “the picture zoomed in on the black dot, and it turned out to be a bird. Big letters appeared beneath. ‘R A V E N,’ the book said. ‘Raven. Now, say it with me.’ ‘Raven.’ ”

Later, she asks, “What’s an adventure?” and “both pages filled with moving pictures of glorious things: girls in armor fighting dragons with swords, and girls riding white unicorns through the forest, and girls swinging from vines, swimming in the blue ocean, piloting rocket ships through space. . . . After awhile all of the girls began to look like older versions of herself.”

I admire what Khan Academy is trying to do for education..which, in America at least, needs all the help it can get…and I’m sure that AI has a lot of potential in this field. But a couple of things are bothering me here.

First, that Raven sequence. Is it really a good idea to teach reading with all those dramatic visual effects? Won’t kids later be disappointed when attempting to read anything that doesn’t include such effects? Indeed, I believe such concerns were raised, years ago, about Sesame Street.

Perhaps more importantly, consider that line After awhile all of the girls began to look like older versions of herself. Really? Do we want to bring up people who are so focused on themselves that they can’t identify with even fictional characters who don’t look like themselves? Might be of different ethnicity, difference gender, different age. I thought the development such broader perspective was supposed to be one of the purposes of education in general and of literature in particular.

Adam talks about God, the Forbidden tree, sleep, the difference between beast and man, his plans for the morrow, the stars and the angels. He discusses dreams and clouds, the sun, the moon, and the planets, the winds and the birds. He relates his own creation and celebrates the beauty and majesty of Eve…Adam, though locally confined to a small park on a small planet, has interests that embrace ‘all the choir of heaven and all the furniture of earth.’ Satan has been in the heaven of Heavens and in the abyss of Hell, and surveyed all that lies between them, and in that whole immensity has found only one thing that interests Satan.. And that “one thing” is, of course, Satan himself…his position and the wrongs he believes have been done to him. “Satan’s monomaniac concern with himself and his supposed rights and wrongs is a necessity of the Satanic predicament…”

From Harvard:

Young people are very, very concerned about the ethics of representation, of cultural interaction—all these kinds of things that, actually, we think about a lot!” Amanda Claybaugh, Harvard’s dean of undergraduate education and an English professor, told me last fall. She was one of several teachers who described an orientation toward the present, to the extent that many students lost their bearings in the past. “The last time I taught ‘The Scarlet Letter,’ I discovered that my students were really struggling to understand the sentences as sentences—like, having trouble identifying the subject and the verb,” she said. “Their capacities are different, and the nineteenth century is a long time ago.”

Reading the above, the first thing that struck me was that a university dean, especially one who is an English professor, should not view the 19th century as ‘a very long time ago’…most likely, though, she herself probably does not have such a foreshortened view of time, rather, she’s probably describing what she observes as the perspective of her students (though it’s hard to tell from the quote). It does seem very likely that the K-12 experiences of the students have been high on presentism, resulting in students arriving at college “with a sense that the unenlightened past had nothing left to teach,” as a junior professor who joined the faulty in 2021 put it. One would hope, though, that to the extent Harvard admits a large number of such students, it would focus very seriously on challenging that worldview. I do not get the impression that it actually does so.

In a discussion of the above passage at Twitter, Paul Graham @PaulG said:

One of the reasons they have such a strong “orientation toward the present” is that the past has been rewritten for a lot of them.

to which someone responded:

that’s always been true! it’s not like the us didn’t rewrite the history of the civil war to preserve southern feelings for 100 years. what’s different is that high schools are no longer providing the technical skills necessary for students to read literature!

…a fair point that there’s always been some rewriting of history going on, or at least adjusting the emphasis & deemphasis of certain points, but seems to me that what is going on today is a lot more systematic and pervasive than what’s happened in the past, at least in the US. Changing the narratives on heroes and villains, selecting particular facts to emphasize (or even to make up out of whole cloth) is not the same thing as inculcating a belief that “the unenlightened past has nothing left to teach.”

I get the impression that a lot of ‘educators’, at all levels, have not much interest in knowledge, but are rather driven by some mix of (a) careerism, and (b) ideology. For more on this, see my post Classics and the Public Sphere.

And it’s also true that many schools are not providing students with the skills necessary to read literature–although there are certainly some schools that are much better than others in this area, and one would have hoped that graduates of such schools would be highly represented among those selected to become Harvard students. Maybe not. And technologies that encourage a short attention span–social media, in particular–surely also play a part in the decline of interest and ability to read and understand even somewhat-complex literature.

Trafalgar Day was marked last week, and I remembered again the essay written in 1797 by a Spanish naval official, Don Domingo Perez de Grandallana, on the question: “Why do we keep losing to the British, and what can we do about it?”

An Englishman enters a naval action with the firm conviction that his duty is to hurt his enemies and help his friends and allies without looking out for directions in the midst of the fight; and while he thus clears his mind of all subsidiary distractions, he rests in confidence on the certainty that his comrades, actuated by the same principles as himself, will be bound by the sacred and priceless principle of mutual support.

Accordingly, both he and his fellows fix their minds on acting with zeal and judgement upon the spur of the moment, and with the certainty that they will not be deserted. Experience shows, on the contrary, that a Frenchman or a Spaniard, working under a system which leans to formality and strict order being maintained in battle, has no feeling for mutual support, and goes into battle with hesitation, preoccupied with the anxiety of seeing or hearing the commander-in-chief’s signals for such and such manoeures…

Thus they can never make up their minds to seize any favourable opportunity that may present itself. They are fettered by the strict rule to keep station which is enforced upon then in both navies, and the usual result is that in one place ten of their ships may be firing on four, while in another four of their comrades may be receiving the fire of ten of the enemy. Worst of all they are denied the confidence inspired by mutual support, which is as surely maintained by the English as it is neglected by us, who will not learn from them.

Imagine Don Grandallana’s feelings when, eight years later, he read the reports of the Spanish naval catastrophe at Trafalgar. He had accurately diagnosed the key problems of his side, but had been unable to bring about the sweeping changes necessary to address them.

There are uncomfortable parallel in America today to the polities and mindset that Grandallana observed in his headed-for-defeat Spain.

Over at Ricochet, the physician who posts as Dr Craniotomy describes the extent to which his time is devoted to satisfying the bureaucracy and its systems.

It’s 9 p.m. on a Friday and I’m waiting for my hospital’s slow, clunky electronic health record (EHR) to load. I’m logging in from home because the administration emails became threatening.,,,The patients were already seen by me, and the notes written by either a resident or nurse practitioner. The hospital just can’t bill until I click the “cosign” button.

Meanwhile, there’s this JAMA article outlining how the National Academy of Medicine is going to tackle physician burnout. The plan revolves around installing a “culture of well-being” into the healthcare workplace. They want to develop training protocols to address discrimination, bullying, and harassment while increasing leadership roles such as Chief Wellness Officers. This sounds like more bureaucratic busywork to complete and administrators to answer to. I would be shocked to find out that there was a single aliquot of improved wellness from a wellness module.

I have governmentally mandated appropriate use criteria that questions every imaging order I place on a patient, forcing me to click box after box, justifying an MRI that I know is clinically indicated because I spent 12 years training in neurological surgery to know exactly when an MRI is indicated.

I have the joint commission telling me I’m not prescribing enough pain medication one day and the next day, I’m being threatened with manslaughter charges if I don’t check a slow, cumbersome, often nonfunctional online database every time I write a prescription.

As I noted in comments to the post: The “culture of compliance” and the micromanagement of employees by bureaucracies and by rigid automated systems, as practiced in America today, bear a disturbing resemblance to the cultural practices that Don de Grandallana identified as the main cause of his country’s repeated defeats.

There is a great deal of this kind of thing in many parts of America today, and trends have been running that way for a long time. See this Washington Post article from 2005, back when the WP was not yet totally politicized: Over-Ruled. Discussing hurricane response and some of the bureaucratic obstacles that appeared, the author says: “We’ve become a society of rule-followers and permission-seekers.”

Causes of this situation are multiple; certainly one factor is the prevalence of litigation. Another is the proliferation of top-down automated systems. And one factor, I think is the excessive emphasis on formal education and the associated credentials. In his post The Most Precious Resource is Agency, Simon Sarris observes that when looking at people who became highly successful in earlier times, “the individuals were all doing from a young age, as opposed to merely schooling.”

He goes on to say:

It seems that the more you ask of people, and the more you have them do, the more they are able to later do on their own. It is important to note that while we shouldn’t allow children to be bobbin boys, no one would describe Steve Job’s summer job at 13 as his exploitation. We should be thinking much harder about making sure children can make meaningful contributions to the world.

also

And I suspect the downplaying of agency in childhood not only creates fewer opportunities for great people, it must also create more marginal people. Ushering everyone into an endless default script is disastrous when underlying conditions or assumptions change. Even when they don’t, some people exit academia almost terrified to leave (to interact with the “real world”), a kind of Stockholm syndrome.

Does an assumption that people will spend 16 or 20 consecutive years in formal education…and the related assumption that this formal education will be the most important factor in their future success or lack of same…reduce the sense of individual agency? I think it probably does.

Also, this brings us to another factor that Grandallana did not mention, either because he didn’t see it as a problem or because he didn’t dare talk about it: the dominance of a hereditary aristocracy. I think it’s pretty clear to historians now that one major reason for Spain’s naval failures was that people tended to be placed in command positions because of their titles and bloodlines, rather than their demonstrated competence.

We don’t have a formal aristocracy in the US, of course; indeed, the Constitution explicitly prohibits any such thing. But while educational credentialism was initially sold as a form of meritocracy, and indeed did initially lead to some progress in that direction, it has devolved in too many cases to a form of aristocracy light, where obtaining the most ‘elite’ credential is largely a matter of conducting your early life in a manner of which admissions officers approve–including demonstrating the ‘right’ social attitudes–and, often, of having the right family and connections, rather than a matter of true performance-related merit.

More than 50 years ago, Peter Drucker wrote that a major advantage America had over Europe is that access to key roles in society was not controlled by a admission to a small number of ‘elite’ universities.

The Harvard Law School might like to be a Grande Ecole and to claim for its graduates a preferential position. But American society has never been willing to accept this claim…

American society today is much closer to accepting that and similar claims than it was when Drucker wrote the above in 1969, and I think this has something to do with the dysfunctionality of many of our institutions.

For discussion: How far are we down the road to the kind of environment that Grandallana described? What are the causes, and what are the potential paths for reversal?