Kevin Meyer, in his post Leveraging the Solitude of Leadership, cites a lecture delivered at West Point by essayist William Deresiewicz…who started by describing his experience on the Yale admissions committee:

The first thing the admissions officer would do when presenting a case to the rest of the committee was read what they call the “brag” in admissions lingo, the list of the student’s extracurriculars.

So what I saw around me were great kids who had been trained to be world-class hoop jumpers. Any goal you set them, they could achieve. Any test you gave them, they could pass with flying colors. They were, as one of them put it herself, “excellent sheep.” I had no doubt that they would continue to jump through hoops and ace tests and go on to Harvard Business School, or Michigan Law School, or Johns Hopkins Medical School, or Goldman Sachs, or McKinsey consulting, or whatever. And this approach would indeed take them far in life.

That is exactly what places like Yale mean when they talk about training leaders. Educating people who make a big name for themselves in the world, people with impressive titles, people the university can brag about. People who make it to the top. People who can climb the greasy pole of whatever hierarchy they decide to attach themselves to.

But I think there’s something desperately wrong, and even dangerous, about that idea.

Dangerous how? Largely because of all that emphasis on hoop-jumping…

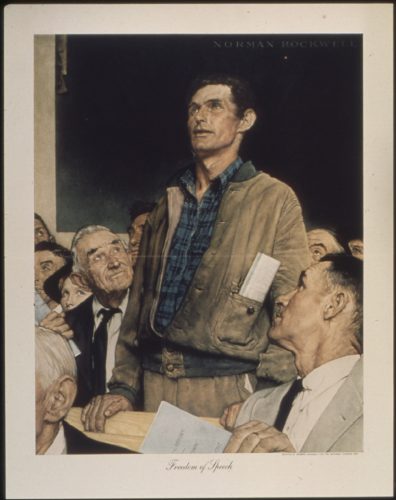

What we don’t have, in other words, are thinkers. People who can think for themselves. People who can formulate a new direction: for the country, for a corporation or a college, for the Army—a new way of doing things, a new way of looking at things. People, in other words, with vision.

A couple of weeks ago, a WSJ bookshelf piece titled The Price of Admission reviewed Little Platoons, by Matt Feeney, the theme of which is “a growing incursion of market forces into the family home.”

In the ambitious, competitive environments that Mr Feeney describes, year-round sports clubs and camps promote not joyful play or healthy exertion but ‘development’ and preparation for advancement to ‘the next level’–where the good, choiceworthy thing is always a few hard steps away. If there is a terminus to this process, it is admission to a good college, which is, for many of the parents Mr Feeney describes, the all-encompassing goal of child-rearing.

As a result, the most powerful and insidious interlopers in Mr Feeney’s story turn out to be elite college admissions officers. These distant commissars quietly communicate a vision of the 18-year-old who will be worthy of passing between their ivied arches, and ‘eager, anxious, ambitious kids’, the author tells us, upon ‘hearing of the latest behavioral and character traits favored by admissions people, will do their best to affect or adopt these traits.’

The emphasis on college admissions, especially ‘elite’ college admissions, has given enormous power to the administrators involved in this process–people who are ‘vain and blinkered’, in Mr Feeney’s words. They are also capricious:

Admissions officers once looked favorably upon students who captained every team, founded every club and spent every school break building homes in Africa and drilling for the SATs. Ambitious students and parents obliged, shaping family life in accordance to those preferences. In time, though, colleges found themselves deluged with résumé-padding renaissance students. Doing everything was no longer a sign of distinction, so admissions personnel changed the signals they were sending. “Now,” Mr. Feeney says, “instead of ‘well-rounded’ generalist strivers, admissions officers favor the passionate specialist, otherwise known as the ‘well-lopsided’ applicant.” Striving families are only too happy to comply.

I haven’t read Mr Feeney’s book, but at least as far as the college admissions process goes, I’d question whether it reflects ‘the intrusion of market forces’ into family life–if America was to go all the way to government ownership and control of those functions now performed by businesses, the malign effects of the admissions hoop-jumping described by the author would be just about the same.

In any case, people who are taught to center their lives and personalities around this admissions process, and the subsequent educational experience, are unlikely to be either first-class innovators or first-class leaders.

And, worse, the process makes them less likely to become thoughtful and courageous citizens. In the comments to this post, commenter OBloodyHell quoted Walt Whitman:

There is no week nor day nor hour when tyranny may not enter upon this country, if the people lose their roughness and spirit of defiance.

“Roughness and spirit of defiance” are not likely to be compatible with the admissions process…and the education…that are all too common in American universities today.