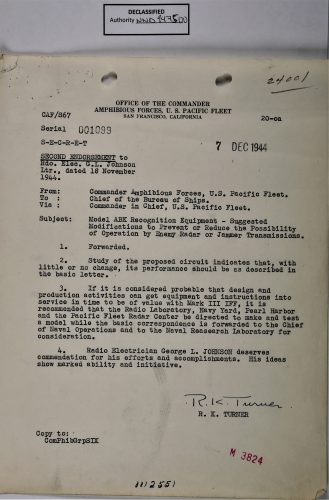

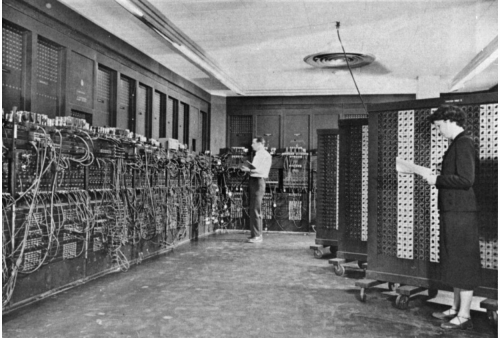

In February 1946, the first general purpose electronic computer…the ENIAC…was introduced to the public. Nothing like ENIAC had been seen before, and the unveiling of the computer, a room-filling machine with lots of flashing lights and switches–made quite an impact.

ENIAC (the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) was created primarily to help with the trajectory-calculation problems for artillery shells and bombs, a problem that was requiring increasing numbers of people for manual computations. John Mauchly, a physics professor attending a summer session at the University of Pennsylvania, and J Presper Eckert, a 24-year-old grad student, proposed the machine after observing the work of the women (including Mauchly’s wife Mary) who had been hired to assist the Army with these calculations. The proposal made its way to the Army’s liason with Penn, and that officer, Lieutenant Herman Goldstine, took up the project’s cause. (Goldstine apparently heard about the proposal not via formal university channels but via a mutual friend, which is an interesting point in our present era of remote work.) Electronics had not previously been used for digital computing, and a lot of authorities thought an electromechanical machine would be a better and safer bet.

Despite the naysayers (including RCA, actually which refused to bid on the machine), ENIAC did work, and the payoff was in speed. This was on display in the introductory demonstration, which was well-orchestrated from a PR standpoint. Attendees could watch the numbers changing as the flight of a simulated shell proceeded from firing to impact, which took about 20 seconds…a little faster than the actual flight of the real, physical shell itself. Inevitably, the ENIAC was dubbed a ‘giant brain’ in some of the media coverage…well, the “giant” part was certainly true, given the machine’s size and its 30-ton weight.

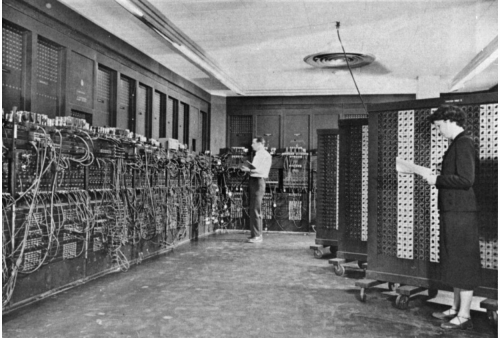

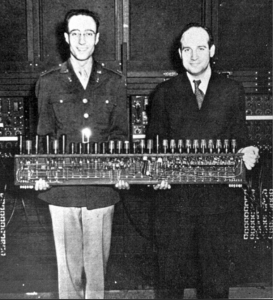

In the photo below, Goldstine and Eckert are holding the hardware module required for one single digit of one number.

The machine’s flexibility allowed it to be used for many applications beyond the trajectory work, beginning with modeling the proposed design of the detonator for the hydrogen bomb. Considerable simplification of the equations had to be done to fit within ENIAC’s capacity; nevertheless, Edward Teller believed the results showed that his proposed design would work. In an early example of a disagreement about the validity of model results, the Los Alamos mathematician Stan Ulam thought otherwise. (It turned out that Ulam was right…a modified triggering approach had to be developed before working hydrogen bombs could be built.) There were many other ENIAC applications, including the first experiments in computerized weather forecasting, which I’ll touch on later in this post.

Programming ENIAC was quite different from modern programming. There was no such thing as a programming language or instruction set. Instead, pluggable cable connections, combined with switch settings, controlled the interaction among ENIAC’s 20 ‘accumulators’ (each of which could store a 10-digit number and perform addition & subtraction on that number) and its multiply and divide/square-root units. With clever programming it was possible to make several of the units operate in parallel. The machine could perform conditional branching and looping…all-electronic, as opposed to earlier electromechanical machines in which a literal “loop” was established by glueing together the ends of a punched paper tape. ENIAC also had several ‘function tables’, in which arrays of rotary switches were set to transform one quantity into another quantity in a specified way…in the trajectory application, the relationship between a shell’s velocity and its air drag.

The original ‘programmers’…although the word was not then in use…were 6 women selected from among the group of human trajectory calculators. Jean Jennings Bartik mentioned in her autobiography that when she was interviewed for the job, the interviewer (Goldstine) asked her what she thought of electricity. She said she’d taken physics and knew Ohm’s Law; Goldstine said he didn’t care about that; what he wanted to know was whether she was scared of it! There were serious voltages behind the panels and running through the pluggable cables.

“The ENIAC was a son of a bitch to program,” Jean Bartik later remarked. Although the equations that needed to be solved were defined by physicists and mathematicians, the programmers had to figure out how to transform those equations into machine sequences of operations, switch settings, and cable connections. In addition to the logical work, the programmers had also to physically do the cabling and switch-setting and to debug the inevitable problems…for the latter task, ENIAC conveniently had a hand-held remote control, which the programmer could use to operate the machine as she walked among its units.

Notoriously, none of the programmers were introduced at the dinner event or were invited to the celebration dinner afterwards. This was certainly due in large part to their being female, but part of it was probably also that programming was not then recognized as an actual professional field on a level with mathematics or electrical engineering; indeed, the activity didn’t even yet have a name. (It is rather remarkable, though, that in an ENIAC retrospective in 1986…by which time the complexity and importance of programming were well understood…The New York Times referred only to “a crew of workers” setting dials and switches.)

The original programming method for ENIAC put some constraints on the complexity of problems that it could be handled and also tied up the machine for hours or days while the cable-plugging and switch-setting for a new problem was done. The idea of stored programming had emerged (I’ll discuss later the question of who the originator was)…the idea was that a machine could be commanded by instructions stored in a memory just like data; no cable-swapping necessary. It was realized that ENIAC could be transformed into a stored-program machine with the function tables…those arrays of rotary switches…used to store the instructions for a specific problem. The cabling had to be done only once, to set the machine up for interpreting a particular vocabulary of instructions. This change gave ENIAC a lot more program capacity and made it far easier to program; it did sacrifice some of the speed.

Read more