(inspired by Are You an Alpha or a Beta Male? Take Our 20-Question Quiz and Find Out and the Bill of Rights)

Anglosphere

The Privileged and the Ruling Class

One of my internet guilty pleasures is perusing the website of the UK’s Daily Mail newspaper, both the US and UK sides. I know in the grand scheme of things, the Daily Mail is about one half-step up from a tabloid. The captions and headlines often give evidence of being written by middle-school students innocent of any knowledge of conventional grammar or spelling, they employ the execrable Piers Morgan, editorially despise Donald Trump, and have this inexplicable and unholy fascination with all things Kardashian. In my early blogging days, I favored the rather more high-class Times of London, and the Telegraph, but they went all pay-wall and frankly, hard to read. In any case and against the above-listed foibles and more, the Daily Mail is a free and straightforward read. Start at the top and scroll down; no hopscotching around to the various menu headings, hoping to get lucky and find something interesting. They nearly always do provide some daily amusement, or horror, depending on tastes. And they cover American news without fear or favor although, as noted, they have no abiding affection for The Donald. They didn’t have for The Barack, either, so I’ll take what I can get, for easy AM reading.

This week’s headline bruhaha made the American conservative side of the blogosphere develop that kind of nervous eyelid twitch demonstrated by Inspector Clouseau’s boss in the classic Pink Panther series: an elderly retiree in a distant London suburb surprised a pair of burglars who had broken into his house in the middle of the night with the intent of robbery and god knows what other kind of criminal mayhem. This being England, land of hope and glory and strict gun control, the thirty-something burglar (who had a comprehensive record as an honest-work-shy professional criminal) was armed with an assault screwdriver, with which he menaced the home-owner. Much to everyone’s surprise including, no doubt, the professional burglar and his faithful sidekick the elderly retiree succeeded in defending himself against a pair of younger and presumably bigger men. Indeed, one of the felonious pair was stabbed fatally with his own screwdriver, collapsing in the street outside, whereupon his faithful sidekick abandoned him, gunned their escape vehicle, and vanished in a cloud of exhaust. (The police are searching for him, at last result, although they have located the burned-out escape vehicle. So much for honor among thieves, and the ability of the London police force.) The assault screwdriver-wielding professional career criminal was found, bloodied and dying in the street, taken to a hospital, wherein he expired. Well, they always said that crime doesn’t pay, even though for him it seemed that the eventual bill was a long time coming.

Quote of the Day (Follow Up)

Mr. Trump isn’t the problem, but among the symptoms of the problem are that the director and deputy director of the FBI have been fired for cause as the Bureau virtually became the dirty-tricks arm of the Democratic National Committee, and that, as the Center for Media Studies and Pew Research have both recorded, 90% of national-press comment on Mr. Trump is hostile. Mr. Trump may have aggravated some of the current nastiness, but his chief offense has been breaking ranks with the bipartisan coalition that produced the only period of absolute and relative decline in American history.

I think Black is too harsh on George W. Bush but this column is otherwise excellent.

Quote of the Day

Here are two current examples of [the failings of the legal system and of journalism]: Canadians don’t like Donald Trump, largely because his confident and sometimes boorish manner is un-Canadian. He is in some respects a caricature of the ugly American. But he has been relentlessly exposing the U.S. federal police (FBI) as having been politicized and virtually transformed into the dirty tricks division of the Democratic National Committee. Few now doubt that the former FBI director, James Comey, was fired for cause, and the current director, backed by the impartial inspector general and Office of Professional Responsibility, asserts that Comey’s deputy director, Andrew McCabe, was also fired for cause. There are shocking revelations of the Justice Department’s illegal use of the spurious Steele dossier, paid for by the Clinton campaign, and of dishonest conduct in the Clinton email investigation, the propagation of the nonsense that Trump had colluded with Russia, and of criminal indiscretions and lies in sworn testimony by Justice officials. It is an epochal shambles without the slightest precedent in American history (certainly not the Watergate piffle), yet our media slavishly cling to a faded story of possible impeachable offences by the president.

The American refusal to adhere to the Paris climate accord is routinely portrayed as anti-scientific heresy and possibly capitulation to corrupt oil interests. The world’s greatest polluters, China and India, did not promise to do anything in that accord; Europe uttered platitudes of unlimited elasticity, and Barack Obama, for reasons that may not be entirely creditable, attempted to commit the United States to reducing its carbon footprint by 26 per cent, at immense cost in jobs and money, when there is no proof that carbon has anything to do with climate and the United States under nine presidents of both parties has done more for the ecology of the world than any other country. Journalistic failure on this scale, and across most of what is newsworthy, added to an education system that is more of a Luddite day-care network, produces a steadily less informed public, who, while increasingly tyrannized by lawyers, elect less capable public office-holders.

Lenin famously wrote: “What is to be done?” We must ask ourselves the same question but come up with a better answer than he did.

I Am a Barbarian

Scott, James C. Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

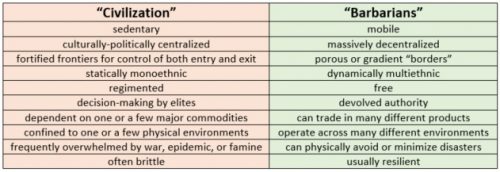

Scott has hit another metaphorical grand slam with this one, a worthily disconcerting follow-on to his earlier work. I have previously read (in order of publication, rather than the order in which I encountered them) The Moral Economy of the Peasant, Seeing Like a State, and Two Cheers for Anarchism, and found them congenial. Scott is particularly good at encouraging a non-elite viewpoint deeply skeptical of State power, and in Against the Grain he applies this to the earliest civilizations. Turns out they loom large in our imagination due to the a posteriori distribution of monumental ruins and written records—structures that were often built by slaves and records created almost entirely to facilitate heavy taxation and conscription. Outside of “civilization” were the “barbarians,” who turn out to have simply been those who evaded control by the North Koreas and Venezuelas of their time, rather than the untutored and truculent caricatures of the “civilized” histories.

By these criteria, the United States of America is predominately a barbarian nation. In the order given above: