Wise words from two old masters…

Arts & Letters

With Greco: two views of Toledo

[ cross-posted from Zenpundit — perception, painting, pre-modern, modern, post-modern, heaven, sky, simulation, John Donne, El Greco ]

.

It is Sunday.

I find it powerfully interesting that the sky as perceived by painters (our “seers” par excellence) used to be filled with supernatural beings and is currently filled with natural ones — a clear sign that our culture has effectively moved from what one might call a theological vision of the world to a meteorological one (with astronomical trimmings under a clear sky)…

And I see that transition captured very precisely in four words, when John Donne writes:

At the round earths imagin’d corners, blow

Your trumpets, Angells, and arise, arise

From death, you numberlesse infinities

Of soules, and to your scattred bodies goe…

The “round earth” is that of modern science, the “imagin’d corners” those of pre-modern maps and angelology.

*

I have to admit, therefore, that I was surprised yesterday evening to come across an El Greco painting of Toledo that featured the blessed Virgin Mary over the city.

I have long been familiar with his better known View of Toledo, which is entirely naturalistic unless you want to consider storm-clouds as portents of a divine presence —

but the second of these images, from the View and Plan of Toledo, came as quite a surprise…

Repose

I have so much I should be doing I keep clamping down so I don’t have a panic attack.

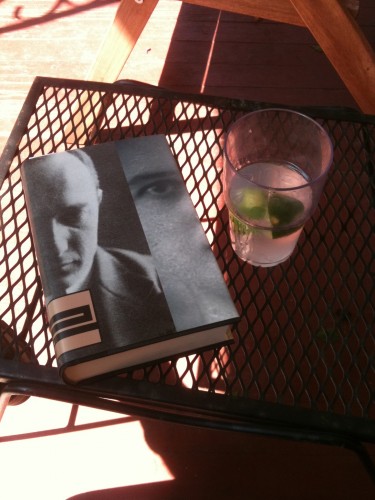

But, its Memorial Day and I am taking it easy. I have been going to read Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities for a long, long time. And I finally bought the highly praised recent translation last year. As a devotee of all things literary pertaining to the final years of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (e.g. the three masterpieces: The Radetzky March by Joseph Roth, and The Snows of Yesteryear by Gregor von Rezzori and The World of Yesterday by Stefan Zweig), Musil is long overdue.

So, I managed to evade the rest of the family and get a few minutes on the front porch with Musil and a stiff glass of lime, ice, tonic water and Tanqueray gin — which was in the back of the cabinet and forgotten until a few days ago.

Chicken and grilled veggies up next.

God bless America.

The Vestigial: It Seems Past – But Remains & Misleads

I’d like to note some minor irritations. Few lead as voyeuristic a life as I do, often using pop culture as a gauge to my reality. I know that betokens superficiality. Well, so be it. I’ve wasted much life in front of television sets and reading murder mysteries. And Humphrey Bogart’s image moved through that life.

So I followed ALDaily’s link to an LRB review of Stefan Kanfer’s Tough Without a Gun: The Life and Extraordinary Afterlife of Humphrey Bogart. Apparently, for Jenny Diski, as for many of us, Humphrey Bogart was bigger than life. He died before I became a teen, but his old movies reran constantly on fifties’ television; when I started college, French directors, as Diski notes, led us back to him. I watched many yet again at Chicago’s Clark in the late sixties. Bogart merged with the heroes of hard boiled thrillers and then Camus as we started to take our intellectual lives more seriously.