A friend of mine posted the above on her Facebook page today. She is an extremely nice person, but believes in nonsense like accupuncture, and the vaccinations are bad for you woo-woo, and other things like that. She is also into all natural foods.

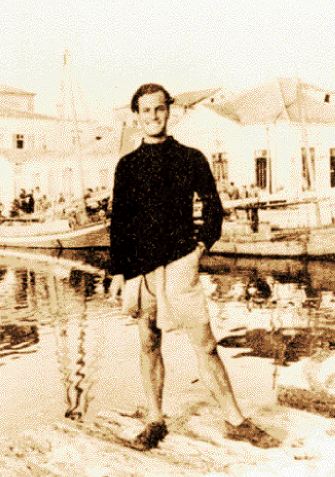

The above reminded me of my grandparents (my father’s parents), who I loved very much and had many great times with when I was a young boy. My Grandmother grew up in squalor in Munich, and my Grandfather did the same in Riga, Latvia. They met in Chicago. I have some photos of my Grandmother and her family in front of their rabbit cages – they raised them for meat. They had no indoor plumbing, of course. This was just after the turn of the century. I don’t have any photos of my grandfather when he was growing up. His father was killed in WW1 and he was shifted from relative to relative. I can only assume that a camera and photos were the last thing on his mind.

I was treated to the way that my grandparents ate when I spent summer weeks at their house in northern Wisconsin (Birchwood, for those who may be interested). We ate all sorts of shit that my friend of today would simply puke on if presented to her. Processed meats, fortified grains, you name it. Coming from the places they did, although they lived a comfortable retirement, they still wasted nothing. If we had chicken for dinner, we would make soup that night or the next day out of the carcass. It wasn’t even a question, we just did it. All the leftovers went into the soup.

I think my favorite was when after a roast or something was cooked, my grandmother would take the rendered fat and wait until it solidified, then scraped it up, put it in the fridge, and hauled it out for a lunch the next day. She would simply spread it on rye bread and that was it. Take it or leave it. My grandpa would wash that down with a beer or two.

This is what people, when they were poor, had to do to scratch it out every day. My comment, which ended all of the “hell yeas!” and “I agrees” in the Facebook thread above was:

I admit I miss the lard and rye bread sandwiches my grandmother used to feed us.

Lack of perspective cracks me up at times.