Neptunus Lex puts you in the cockpit. It’s a long series…you can always pull the Eject lever–but I don’t think you’re going to want to.

Thanks to Bill Brandt for locating and posting this.

Some Chicago Boyz know each other from student days at the University of Chicago. Others are Chicago boys in spirit. The blog name is also intended as a good-humored gesture of admiration for distinguished Chicago School economists and fellow travelers.

I’m currently on Season 5 of this series, which ran for 6 seasons on French TV. Set in the fictional town of Villeneuve during the years of the German occupation and directly afterwards, it is simply outstanding – one of the best television series I have ever seen.

Daniel Larcher is a physician who also serves as deputy mayor, a largely honorary position. When the regular mayor disappears after the German invasion, Daniel finds himself mayor for real. His wife Hortense, a selfish and emotionally-shallow woman, is the opposite of helpful to Daniel in his efforts to protect the people of Villaneuve from the worst effects of the occupation while still carrying on his medical practice. Daniel’s immediate superior in his role as mayor is Deputy Prefect Servier, a bureaucrat mainly concerned about his career and about ensuring that everything is done according to proper legal form.

Daniel’s brother Marcel is a Communist. The series accurately reflects the historical fact that the European Communist parties did not at this stage view the outcome of the war as important–it was only “the Berlin bankers versus the London bankers”…but this is a viewpoint that Marcel has a hard time accepting.

In addition to his underground political activism, Marcel works as a foreman at the lumber mill run by a prominent local businessman, Raymond Schwartz. A strong mutual attraction has developed between Raymond and Marie Germain, a farm wife whose husband is away with the army and is missing in action.

Much of the movie’s action takes place at the local school, where Judith Morhange is the (Jewish) principal and Lucienne Broderie is a young teacher. Jules Beriot, the assistant principal, is in love with Lucienne, but hopelessly so, it seems.

German characters range from Kurt, a young soldier with whom Lucienne shares a love of classical music, all the way down to the sinister sicherheitdienst officer Heinrich Mueller. The characters include several French police officers, who make differing choices about the ways in which they will handle life and work under the Occupation.

The series does a fine job of bringing all these characters–and many more–to life. Very well-written and well-acted, well-deserving of its long run on French television. Highly recommended.

In French, with English subtitles that (unlike the case with many films) are actually readable. Season 1 is available on Amazon streaming, and seasons 2-5 are available there in DVD form. MHZ Networks is another available source for the series. (Season 6, which I believe is now running in France, is not yet available in translation.)

Not to be missed.

A USAF jet fighter pilot flies a WWII P-51 Mustang.

An argument that China will never be as wealthy as America. (‘Never’ is a long time, though)

A huge database of artworks, indexed on many dimensions.

An ethics class that has been taught for 20 years (at the University of Texas-Austin) is no longer offered. According to the professor who taught it:

Students clam up as soon as conversation veers close to anything controversial and one side might be viewed as politically incorrect. The open exchange of ideas that used to make courses such as Contemporary Moral Problems exciting doesn’t happen. It’s not possible to teach the course the way I used to teach it.

At the GE blog: Direct mind-to-airplane communication…and, maybe someday, direct mind-to-mind communication as well. Although regarding the second possibility, SF writer Connie Willis raises some concerns.

Also at the GE blog: The California Duck Must Die – a very good explanation of the load-matching problems created when ‘renewable’ sources become a major element of the electrical grid. Media discussion of all the wind and solar capacity installed has tended to gloss over these issues.

The Battle of the Bulge, December 1944 – January 1945.

One of the important things to know about General Douglas MacArthur was that almost nothing said or written about him can be trusted without extensive research to validate its truthfulness. There were a lot of reasons for this. Bureaucratic infighting inside the US Army, inside the War Department, and between the War and Naval Departments all played a role from MacArthur’s attaining flag rank in World War 1 (WW1) through his firing by President Truman during the Korean War. His overwhelming need to create what amounts to a cult of personality around himself was another.

However, the biggest reason for this research problem was that, if the Clinton era political concept of “The Politics of Personal Destruction” had been around in the 1930s through 1950s, General Douglas MacArthur’s face would have been its poster boy. Everything the man did was personal, and that made everything everyone else did in opposition to him, “personal” to them. Thus followed rounds of name calling, selective reporting and political partisanship that have utterly polluted the historical record and require research over decades to untangle.

A case in point is the December 8th 1941 attack on Clark Field and the massacre of the American B-17 force. This 2007 article by Michael Gough titled “Failure and Destruction, Clark Field, the Philippines, December 8, 1941″ is a good example of the accepted narrative of the Clark Field attack.

The real reason we lost those planes on Dec 8th 1941 was American bad luck, delusion and political ghost dancing meeting a very well prepared Japanese enemy. Luzon was too close to the center of Japanese air power for the Far Eastern Air Force (FEAF) to survive. Nothing MacArthur did or didn’t do would have made a real difference in that outcome.

The following was posted to the Academic H-War listserve back in late May 2012 and addresses the timing of the raid on Clark and Iba fields Dec 8th 1941 —

“Hi Gang

I’ve refrained from commenting on this thread because of the subject’s

complexity, the dearth of primary documents, and a desire to avoid

replying to endless questions, but I will make a bit of an effort here:

From 0330 until 1014, HQ USAFFE specifically denied Brereton permission to

launch his bomber force at Clark (19 B-17s) against the Japanese

facilities on Formosa and did not allow him to speak directly with

MacArthur either in person or on the telephone.

FEAF dispersed the bombers to holding positions in the air at about 0800

to avoid an attack expected that morning. Most of the bombers were in the air

most of that morning.

MacArthur gave Brereton permission to attack Formosa during a telephone

call at 1014, and Brereton recalled the dispersed force which began landing

about 1100.

It took two to two and a half hours to refuel, load bombs, and prepare an attack,

thus FEAF’s aircraft were on the ground at about 1220 when the Japanese air

forces, delayed by fog on Formosa for roughly five hours, reached Clark.

USAFFE persistently denied Brereton’s efforts to conduct reconnaissance of

Formosa prior to 8 December, but the 19th Bomb Group’s target files

apparently contained enough information that, although dated, made an

attack on Formosa more than just a thrust into the unknown.

Who ignored MacArthur’s chain of command and in what way?

I am still working on my biography of Lt. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton.

Hopefully, it will get done.

Cheers,

Roger G. Miller, Ph.D., GS-14

Deputy Director

Air Force Historical Studies Office

HQ USAF/HOH

Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling

Washington, D.C. 20373-5899”

So the Far Eastern Air Force (FEAF) took precautions to protect their B-17s from a dawn Japanese strike on Dec 8, 1941, but as Dr. Miller mentioned, they landed out of fuel just in time for the delayed-by-fog Japanese naval air force strike from Tainan Airfield, Formosa.

Today is the 75th anniversary of the December 7th, 1941 Imperial Japanese Navy’s (IJN) surprise aerial attack on the American Pacific Fleet’s “Battleship Row” at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. With this air attack, and air attacks in the following weeks on Clark Field in the Philippines, and on the British fleet off Malaya — sinking the new British battleship Prince of Wales and the WW1 era battlecruiser Repulse — the Japanese established unchallenged air and naval superiority across the Pacific and ran wild for six months.

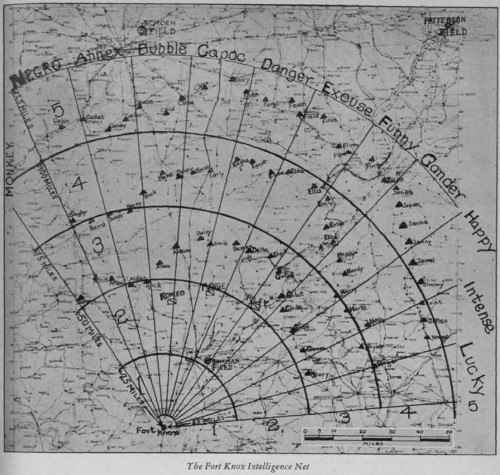

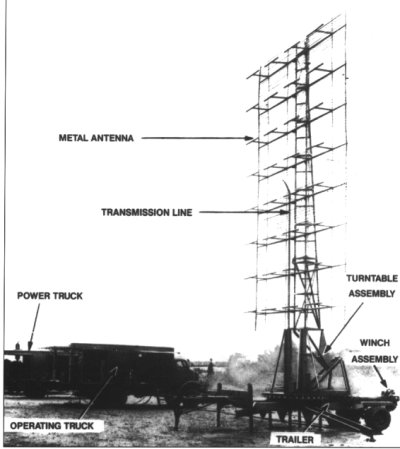

The key failure that day leading up to the attack — A final point falure in a years long list of failures starting with the US Army Air Corps purge of fighter advocate Claire Chennault for his all too successful telephone-equipped ground observer air warning network that threatened the budget of the B-17 heavy bomber — was the ignored warning from the US Army SCR-270B radar at Opana Point, Hawaii as the IJN Strike Force flew in.

In 2012 I discovered the book ECHOES OVER THE PACIFIC: An overview of Allied Air Warning Radar in the Pacific from Pearl Harbor to the Philippines Campaign by Ed Simmonds and Norm Smith that explained some of the reasons for that last failure. ECHOS is the story of Australian and wider Anglosphere efforts to field radar in the Pacific during WW2. This year I also found John Bennet’s “SIGNAL COMPANY, AIRCRAFT WARNING, HAWAII ORGANIZATIONAL HISTORY” which expanded on and clarified the background to those failures further.

ECHOS has these passages regarding the bureaucratic and political failings of radar deployment at Pearl Harbor: