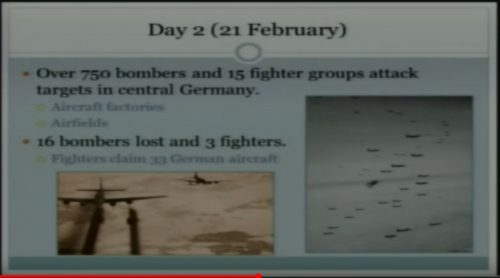

Today marks the 75th Anniversary of the second day of Operation Argument otherwise known as BIG WEEK. On Monday, February 21, 1944 the 8th Air Force went after the Luftwaffe in the skies over Germany for a second day to take air superiority for the Normandy invasion in June 1944.

These were the results of the 2nd day of combat —

Mission 228: 3 areas in Germany are targeted with the loss of 16 bombers and 5 fighters:

.

- 336 B-17s are dispatched to the Gütersloh, Lippstadt and Werl Airfields; because of thick overcast, 285 hit Achmer, Hopsten, Rheine, Diepholz, Quakenbrück and Bramsche Airfields and the marshaling yards at Coevorden and Lingen; they claim 12-5-8 Luftwaffe aircraft; 8 B-17s are lost, 3 damaged beyond repair and 63 damaged; casualties are 4 KIA, 13 WIA and 75 MIA.

- 281 B-17s are dispatched to Diepholz Airfield and Brunswick; 175 hit the primaries and 88 hit Ahlhorn and Vörden Airfields and Hannover; they claim 2-5-2 Luftwaffe aircraft; five B-17s are lost, three damaged beyond repair and 36 damaged; casualties are 20 KIA, 4 WIA and 57 MIA.

- 244 B-24s are dispatched to Achmer and Handorf Airfields; 11 hit Achmer Airfield and 203 hit Diepholz, Verden and Hesepe Airfields and Lingen; they claim 5-6-4 Luftwaffe aircraft; 3 B-24s are lost, 1 damaged beyond repair and 6 damaged; casualties are three WIA and 31 MIA.

,

Escort for Mission 228 is provided by 69 P-38s, 542 Eighth and Ninth Air Force P-47s and 68 Eighth and Ninth Air Force P-51s; the P-38s claim 0-1-0 Luftwaffe aircraft, 1 P-38 is damaged beyond repair; the P-47s claim 19-3-14 Luftwaffe aircraft, two P-47s are lost, two are damaged beyond repair, three are damaged and two pilots are MIA; the P-51s claim 14-1-4 Luftwaffe aircraft, three P-51s are lost and the pilots are MIA. German losses were 30 Bf 109s and Fw 190s, 24 pilots killed and seven wounded.[12]

,

Mission 229: 5 of 5 B-17s drop 250 bundles of leaflets on Rouen, Caen, Paris and Amiens, France at 22152327 hours without loss.

For extensive background, see this Wikipedia article, where the passage above came from:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Big_Week

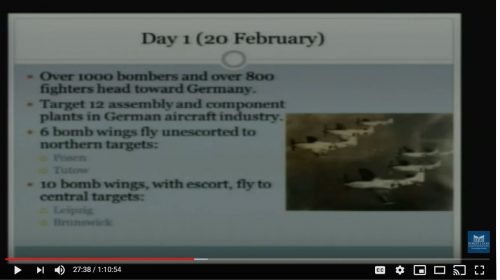

The USAAF Strategy of Big Week

Operation Argument marked a massive strategic change in how the Bomber Generals fought the air war. Previously the idea was that large formations of self-escorting heavy bomber would strike the key parts of the German “industrial web” with “precision bombing” and collapse it’s economy. This “win air superiority through industrial collapse” theory quite literally went down in flames on 14 October 1943 when the second Schweinfurt raid lost 60 bombers, while failing to destroy the German ball bearing industry.

Big Week abandoned this pre-war doctrine. Generals Carl Spaatz and Fred Anderson, respectively commander and chief of operations of United States Strategic Air Forces in Europe, and William Kepner, Eighth Air Force fighter commander decided to fight a different war, a war of attrition, aimed at the German fighter force. The heavy bombers were sent against the German aviation industry, not because they could destroy it — it would be great if they did — but because it was a target that the Luftwaffe had to defend.

Rather than being the single and only war winning super-weapon, the Heavy bomber was demoted to the role of a staked goat. The bomber streams of B-17 and B-24 were bait for the Luftwaffe fighter force to come up into the guns of American escort fighters.