Jeff Carter is raising money to benefit the National World War II Museum, a worthy cause.

Here’s the link to Jeff’s GoFundMe page.

Some Chicago Boyz know each other from student days at the University of Chicago. Others are Chicago boys in spirit. The blog name is also intended as a good-humored gesture of admiration for distinguished Chicago School economists and fellow travelers.

Jeff Carter is raising money to benefit the National World War II Museum, a worthy cause.

Here’s the link to Jeff’s GoFundMe page.

November 9 marked the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Peter Robinson, who drafted President Reagan’s speech including the line Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!, has some thoughts.

Bill Brandt offers some remembrances and some video clips.

Bill’s post mentioned Anna Funder’s excellent book Stasiland: Stories from Behind the Berlin Wall, which I reviewed here.

An interesting website by a former East German MIG-21 pilot.

Before there were electronic digital computers, there were mechanical analog computers. Although now obsolete for practical computation, these devices might actually have an useful future ahead of them–in education.

Mechanical analog computation (analog means that calculation is done by measuring rather than by counting) goes back to the Greek Antikythera mechanism (65 BC), which was used to predict the positions of heavenly bodies. The modern era of analog computing began with the work done by James Thompson and his brother William (Lord Kelvin) in the 1870s. First, James Thompson created a mechanical device that performs the calculus function of integration.

Lord Kelvin applied this device…along with other mechanisms for addition and trigonometric functions…to create a mechanical tide-prediction system. These tide predictors had a pretty good run: the invention was announced in 1876, and some of these systems were still in use in the early 1970s!

For those who haven’t studied calculus, integration can be thought of as a kind of continuous addition. Imagine a hose with a fluctuating flow rate filling a pool: by integrating the rate of flow, you can calculate the volume of water added to the pool.

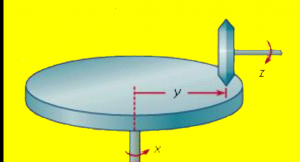

The basic concept of a mechanical integrator is shown below.

If the vertical shaft is turned at a constant rate, and the small wheel is moved in and out according to the changing value of some some variable Y, then the rotation of the horizontal shaft Z will represent the integral of Y with respect to time. If Y is the rate of flow of the a hose, Z will be the total volume added to the pool. If Y represents the acceleration of a vehicle, then the output shaft will give that vehicle’s speed at any moment. Connect the output to the input of another integrator, and you will get the distance traveled.

Vannevar Bush, who would become Roosevelt’s science adviser during WWII, combined the integrator and other computing mechanisms to create a highly general mechanical computer, called a differential analyzer. Completed in 1931, it was not restricted to a single application, but could be programmed–with a wrench and screwdriver to alter the connections–for a wide range of problems. Complex chains of calculation were possible, including the ability for a result at one stage to be fed back as input at an earlier stage–for example, the speed of a simulated vehicle affects its air resistance, which in turn influences its acceleration…which integrates back to its speed.

Other differential analyzers were built in the U.S., Norway, and Britain, and were used for applications including heat-flow analysis, electrical network stability analysis, soil-erosion studies, artillery firing table preparation, and studies of the loading and deflection of beams. It is rumored that a British analyzer was used in the planning for the bouncing-bomb attack on German hydroelectric dams during WWII. Differential analyzers appeared in several movies, including the 1951 film When Worlds Collide (video clip). The ultimate in mechanical analog computation was the Rockefeller Differential Analyzer, a rather baroque (and very expensive) machine built in 1942. It was decommissioned in 1954, on the belief that the future of calculation would belong to the electronic computer, and especially the electronic digital computer. Following the decommissioning, the mathematician Warren Weaver wrote:

It seems rather a pity not to have around such a place as MIT a really impressive Analogue computer; for there is vividness and directness of meaning of the electrical and mechanical processes involved… which can hardly fail, I would think, to have a very considerable educational value. A Digital Electronic computer is bound to be a somewhat abstract affair, in which the actual computational processes are fairly deeply submerged.

A bit of a loaded word, isn’t it? But a label that American anti-slavery activists would have felt entirely comfortable with, in the first half of the 19th century. Such was the knowledge that taking up the cross of a cause could be hazardous, indeed but the fight was for the right, and the eventual prize was worth it and more; the promise that every man (and by implication, every woman as well) had a right to be free. Not a slave, as comfortable as that situation might be to individuals but to be free, answering only to ones’ conscience, as was expressed in the Declaration of Independence. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness…” Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, never mind that one might have varying degrees of success in that pursuit one had the right to decide how to go about it, in whatever method and manner than one chose. One had the right to not be property, as if an ox or a horse.

This movie is focused on the interaction among Thomas Edison, George Westinghouse, and Nikola Tesla in the competition to create and build out America’s…and the world’s…electrical infrastructure. It has gotten mixed and generally not-very-enthusiastic reviews; I thought it was well-done and definitely worth seeing. Visually, it is striking and sometimes even beautiful, thus worth seeing on the big screen.

The movie gets the outline of the history right; also, I think, the essence of the characters. Edison is a brilliant inventor and self-promoter who is committed to his DC-based distribution system and will do some more-than-questionable things to get it universally adopted. Westinghouse, who had invented the railroad air brake (among other things) and already built a large company, sees the value of alternating current, which can be stepped up and down in voltage via transformers and hence can be economically transmitted over long distances. Tesla, a Serbian immigrant and brilliant inventor, provides the missing link in the form of a practical motor that can run on AC power. The relationships of Edison and Westinghouse with their respective wives are highlighted, and the future utility mogul Samuel Insull appears as Edison’s young secretary.

I was happy to see the movie’s positive portrayal of Westinghouse, a great man who has tended to be overshadowed by the more-glamorous figures of Edison and Tesla. (The legions of Tesla fans may be unhappy that Tesla did not get a more central role in the film.)

If this movie sounds interesting to you, better see it soon; I don’t think it’s going to be in the theaters for very long.