Originally posted at The Scholar’s Stage on 20 March 2013.

“The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be.” – Ecclesiastes 1:9 [1]

Over the last few weeks the sections of the blogosphere which I frequent have been filled with predictions, advice, summaries of, and idle chatter about the situation in Ukraine and Crimea. I have refrained from commenting on these events for a fairly simple reason: I am no expert in Russian or Eastern European affairs. Any expertise that my personal experiences or formal studies allows me to claim is on the opposite side of Eurasia. Thus I am generally content to let those who, in John Schindler’s words, “actually know something” take the lead in picking apart statements from the Kiev or the Kremlin. [2] My knowledge of the peoples and regions involved is limited to broad historical strokes.

But sometimes broad historical strokes breed their own special sort of insights.

I have before suggested that one of the benefits of studying history is that it allows a unique opportunity to understand reality from the “Long View.” From this perspective the daily headlines do not simply record the decisions of a day, the instant reactions of one statesmen to crises caused by another, but the outcome of hundreds of choices accumulated over centuries. It allows you to rip your gaze away from the eddies swirling on the top of the water to focus on the seismic changes happening deep below.

To keep the Long View in mind, I often stop and ask myself a simple question as I read the news: “What will a historian say about this event in 60 years? How will it fit into the narrative that the historians of the future will share?”

With these questions are considered contemporary events take on an entirely new significance.

|

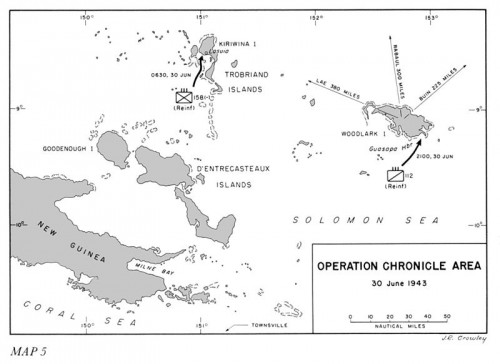

Expansion of Russia, 1533-1894.

Credit: Wikimedia. |

As I have watched affairs in Crimea from afar, my thoughts turn to one such ‘Long View’ narrative written by historian S.C.M. Paine. In Dr. Paine’s peerless The Wars for Asia, 1911-1949 she spares a few paragraphs to explain the broad historical context in which Soviet statesmen made their decisions. She calls this traditional course of Russian statecraft the Russian “strategy for empire”:

she spares a few paragraphs to explain the broad historical context in which Soviet statesmen made their decisions. She calls this traditional course of Russian statecraft the Russian “strategy for empire”:

“The Communists not only held together all of the tsarist empire but greatly expanded it in World War II. They did so in part by relying on Russia’s traditional and highly successful strategy for empire, which sought security through creeping buffer zones combined with astutely coordinated diplomacy and military operations against weak neighbors to ingest their territory at opportune moments. Russia surrounded itself with buffer zones and failing states. During the tsarist period, the former were called governor-generalships, jurisdictions under military authority for a period of initial colonization and stabilization. Such areas generally contained non-Russian populations and bordered on foreign lands.

Russia repeatedly applied the Polish model to its neighbors. Under Catherine the Great, Russia had partitioned Poland three times in the late eighteenth century, crating a country ever less capable of administering its affairs as Russia in combination with Prussia and Austria gradually ate it alive. Great and even middling power on the borders were dangerous. So they must be divided, a fate shared by Poland, the Ottoman Empire, Persia, China, and post World War II, Germany and Korea. It is no coincidence that so many divided states border on Russia. Nor is it coincidence that so many unstable states sit on its periphery” (emphasis added). [3]

It is difficult to read this description and not see parallels with what is happening in Ukraine now (or what happened in Georgia in 2008). Dr. Paine’s description of Russian foreign policy stretches from the 18th century to the middle of the 20th. Perhaps historians writing 60 years hence will use this same narrative–but extend it well into the 21st.

————————————————————

[1] Authorized Version.

[2] John Schindler. “Nobody Knows Anything.” XX Committee. 16 March 2014.

[3] S.C.M. Paine. The Wars for Asia, 1911-1949 . (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012), pp. 83-84.

. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012), pp. 83-84.