I have written in my columns on the end of WW2 in the Pacific about institutional or personally motivated false narratives, hagiography narratives, forgotten via classification narratives and forgotten via extinct organization narratives. Today’s column is revisiting the theme of how generational changes in every day technology make it almost impossible to understand what the World War II (WW2) generation is telling us about it’s times without a lot of research. Recent books on the like John Prados’ “ISLANDS OF DESTINY: The Solomons Campaign and the Eclipse of the Rising Sun” and James D. Hornesfischer’s “NEPTUNES INFERNO: The US Navy at Guadalcanal” focus in the importance of intelligence and the “learning by dying” use of Radar in the Solomons Campaign. Both are cracking good reads and can teach you a lot about that period. Yet they are both missing some very important, generationally specific, professional reasons that the US Navy did so poorly at night combat in the Solomons. These reasons have to do with a transition of technology and how that technology was tied into a military service’s training and promotion policies.

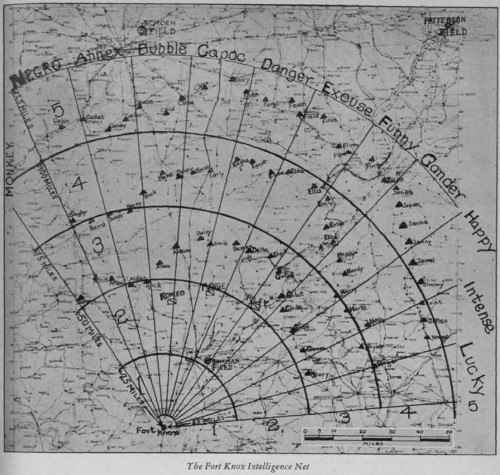

WW2 saw a huge paradigm shift in the US Navy from battleships to aircraft carriers and from surface warship officers, AKA the Black Shoe wearing “Gun Club,” to naval aviators or the Brown Shoe wearing “Airdales.” Most people see this as an abrupt Pearl Harbor related shift. To some extent that was true, but there is an additional “Detailed Reality” hiding behind this shift that US Army officers familiar with both the 4th Infantry Division Task Force XXI experiments in 1997 and the 2003 Invasion of Iraq will understand all too well. Naval officers in 1942-1945, just like Army officers in 1997-2003 were facing a complete change in their basic mode of communications that were utterly against their professional training, in the heat of combat. Navy officers in 1942-1945 were going from a visual communications with flag semaphore and blinking coded signal lamps on high ship bridges to a radio voice and radar screen in a “Combat Information Center” (CIC) hidden below decks. US Army officers, on the other hand, in 1997-2003 were switching from a radio-audio and paper map battlefield view to digital electronic screens. Both switches of communications caused cognitive dissonance driven poor decisions by their users. However, the difference in final results was driven by the training incentives built into these respective military services promotion policies.