Caroline Glick says: Yes. Worth reading.

Judaism

Quote of the Day

What has changed for the Jewish people over the past 75 years isn’t that we have ceased to love the countries where we live. It is that we are no longer compelled to bet—with our lives—that our love will be requited.

From: “Two Scenes From the Grand Synagogue of Paris: Netanyahu, the French national anthem, and what it all means” in Tablet Magazine.

(Via William A. Jacobson)

Book Review: A Time of Gifts

A Time of Gifts, by Patrick Leigh Fermor

In late 1933, Patrick Fermor–then 18 years old–undertook to travel from the Holland to Istanbul, on foot. The story of his journey is told in three books, of which this is the first. This is not just travel writing, it is the record of what was still to a considerable extent the Old Europe–with horsedrawn wagons, woodcutters, barons and castles, Gypsies and Jews in considerable numbers–shortly before it was to largely disappear.

Paddy, as everyone called him, was the child of a British civil servant in India and his wife who remained in Britain. At school, Paddy was an avid student of history, literature, and languages; of math, not so much. He was often in trouble–his housemaster wrote that “he is a dangerous mixture of sophistication and recklessness which makes one anxious about his influence on other boys.” Paddy’s career at the school came to an end after he was caught holding hands with the beautiful 24-year-old daughter of a local grocer. He then knocked around London for a while with a rather Bohemian crowd…his comments on the role of Leftism in this subculture, written many years later, are interesting:

In this breezy, post Stracheyan climate, it was cheerfully and explicitly held that all English life, thought, and art were irredeemably provincial and a crashing bore…The Left Wing opinions that I occasionally heard were uttered in such a way that they seemed a part merely, and a minor part, of a more general emancipation. This was composed of eclectic passwords and symbols–a fluent awareness of modern painting, for instance, of a familiarity with new trends in music; neither more important nor less than acquaintance with nightlife in Paris and Berlin and a smattering of the languages spoken there.

At this stage in his life, Paddy was not very interested in political matters, and his interests when he set out on his walking tour centered on art, architecture, languages/dialects, and folk customs. He didn’t have much money for the trip, and planned on living pretty rough…in the event, his general likeability got him many free stays in homes and taverns, and in some cases introductions from one aristocrat to another. There was still plenty of roughing it, though…in Holland, he found that “humble travelers” were welcome to spend the night in a jail cell, and were even given coffee and bread in the morning…and he spent quite a few nights out-of-doors. (He notes that a night in a castle can be appreciated much more when the previous night has been spent in a hayloft.)

With his considerable knowledge of art, Paddy found Holland to be strangely familiar even though he had never been there before:

Ever since those first hours in Rotterdam a three-dimensional Holland had been springing up all round me and expanding into the distance in conformity with another Holland which was already in existence and in every detail complete. For, if there is a foreign landscape familiar to English eyes by proxy, it is this one…These confrontations and recognition-scenes filled the journey with excitement and delight. The nature of the landscape itself, the colour, the light, the sky, the openness, the expanse and details of the towns and villages are leagued together in the weaving of a miraculously consoling and healing spell.

It did not take him long to cross Holland…”my heels might have been winged”…and soon he was in Germany, where the swastika flag had now been flying for ten months. In the town of Goch was a shop specializing in Nazi paraphernalia. People were gathered around photographs of the Nazi leaders. One woman commented that Hitler was very good-looking; her companion agreed with a sigh, adding that he had wonderful eyes.

For the most part, Paddy was treated in a very friendly way: “There is an old tradition in Germany of benevolence to the wandering young: the very humility of my status acted as an Open Sesame to kindness and hospitality.” In a bookstore he met Hans, a Cologne University graduate with a strong interest in literature, who invited him to stay at his apartment. The landlady joined them for tea, and expressed quite different opinions from those Paddy had heard at the Nazi store in Goch. “Such a mean face!” she observed about Hitler, “and that voice!” Hans and his bookseller friend were also anti-Nazi. Paddy observes that “it was a time when friendships and families were breaking up all over Germany” over the political question.

Hans arranged a ride for Paddy up-river with a barge tow, and he got off at Coblenz to continue on foot. Christmas Eve was spent at an inn in Bingen, where Paddy was the only customer. He was invited to help decorate the Christmas tree and to join them for church that evening. On the day before New Year’s, he stopped at a Heidelberg inn called the Red Ox, “an entrancing haven of oak beams and carving and alcoves and changing floor levels,” where an elderly woman greeted him with a smile and the question “Who rides so late through night and wind?”, which Paddy did not then recognize as the first line of Goethe’s Erlkoening. She and her husband were the owners of the inn, and invited Paddy to stay for a while. Paddy became friendly with Fritz, the son of the owners, and pestered him with questions about student life at Heidelberg, especially the custom of dueling with sabres. “Fritz, who was humane, thoughtful and civilized and a few years older than me, looked down on this antique custom and he answered my question with friendly pity. He knew all too well the dark glamour of the Mensur among foreigners.” (Many years later, Paddy wrote to discover what had become of this family, and discovered that Fritz had been killed in the fighting in Norway, where a battalion of his own regiment at the time had been engaged.)

When walking long distances, Paddy liked to either sing or recite poetry. Germans were very used to people singing as they walked, and such tunes as Shuffle off the Buffalo, Bye Bye Blackbird, and Shenandoah generally resulted in “tolerant smiles” from other wayfarers. Poetry, on the other hand, tended to cause “raised eyebrows and a look of anxious pity”…even, sometimes, “stares of alarm.” One woman who was gathering sticks dropped them and took to her heels, evidently taking Paddy for a dangerous lunatic.

Paddy devotes several pages to the names of poems that he remembers reciting, ranging from the choruses of Henry V and long stretches of A Midsummer Night’s Dream to Marlowe, Spencer, Browning; Kipling and Houseman…in French, Baudelaire, Verlaine, and large quantities of Villon. In Latin, there was Virgil, Catallus, and Horace; also some profane medieval Latin lyrics. And also a bit of Greek, including part of the Odyssey and two poems of Sappho. Amusingly, Paddy prefaces this section of the book with the statement “The range is fairly predictable and all too revealing of the scope, the enthusiams and limitations, examined at the eighteenth milestone, of a particular kind of growing up,” and ends it with the rather apologetic “a give-away collection…a fair picture, in fact, of my intellectual state-of-play…”

At a cafe in Stuttgart, he fell into conversation with two cheerful girls, Annie and Lise, who had come in to buy groceries. They invited him to a “young people’s party” in celebration of the Feast of the Three Kings, and then insisted that he stay overnight. (Annie’s parents were out of town.) The next day was rainy; the girls insisted that he stay longer and go to another party with them, this being one they were not looking forward to but couldn’t get out of: it was being held by an unlikeable business associate of Annie’s father.

The was “a blond, heavy man with bloodshot eyes and a scar across his forehead,” and “except for the panorama of Stuttgart through the plate glass, the house was hideous”…Paddy devotes quite a few words to critiquing its interior decoration. Particularly appalling was a cigarette case made from a seventeenth-century vellum-bound Dante, with the pages glued together and scooped hollow. The trio was very happy to finally escape and return to Annie’s residence. (After Paddy left to continue his journey, he wrote the girls and discovered that the wine bottles they had “recklessly drained” had been a rare and wonderful vintage that Annie’s father had been particularly looking forward to. “Outrage had finally simmered down to the words: “Well, your thirsty friend must know a lot about wine.” (Totally untrue.) “I hope he enjoyed it.” (Yes) It was years before the real enormity of our inroads dawned on me.”)

The Kurds and the Israelis are our only allies in the middle east.

The growth of the terrorist state ISIS has taken all the attention lately. This is just a resurgence of al Qeada in the vacuum left by Obama’s withdrawal of all US troops. Maybe, if we had kept a significant force in Iraq, something could be saved of all we bought at such terrible cost. Now, it is too late.

We do have allies worth helping but they are not in the Iraqi government. It is Shia dominated and dependent on Iran for support. They have alienated the Sunnis and the growth of ISIS is the result. We still have the Kurds as allies and they know we were their only hope in 1993. Jay Garner did a great job working with them once we decided to protect them after the First Gulf War. I have never understood why he was dismissed by George W Bush.

The Kurds have been an embarrassment for us for decades in the middle east because they occupy parts of three nations, two of which were at one time our allies.

Kurdistan includes parts of Iraq, Turkey and Iran. They have never had a modern nation and the neighbors are enemies. Only the mountains have protected them. Now, it is time we did something. Iran is certainly no friend. Iraq has dissolved and it is time to allow it to be broken up into the Sunni, Shia and Kurdish provinces it should be. Turkey is increasingly Islamist and has not been an ally at least since 2003 when they blocked our 4th Infantry Division from invading Iraq from the north.

The 4th was initially ordered to deploy in January 2003 before the war began, but did not arrive in Kuwait until late March. The delay was caused by the inability of the United States and Turkey to reach an agreement over using Turkish military bases to gain access to northern Iraq, where the division was originally planned to be located. Units from the division began crossing into Iraq on April 12, 2003.

The Kurds know this is their opportunity and Dexter Filkins’ piece in the New Yorker makes this clear.

The incursion of ISIS presents the Kurds with both opportunity and risk. In June, the ISIS army swept out of the Syrian desert and into Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city. As the Islamist forces took control, Iraqi Army soldiers fled, setting off a military collapse through the region. The Kurds, taking advantage of the chaos, seized huge tracts of territory that had been claimed by both Kurdistan and the government in Baghdad. With the newly acquired land, the political climate for independence seemed promising. The region was also finding new economic strength; vast reserves of oil have been discovered there in the past decade. In July, President Barzani asked the Kurdish parliament to begin preparations for a vote on self-rule. “The time has come to decide our fate, and we should not wait for other people to decide it for us,” Barzani said.

The Kurds were surprised and routed by ISIS mostly due to limited weapons and ammunition. We could supply the deficit but Obama seems to be oblivious to the true situation. The Iraqi Army will not fight, a characteristic of all Arab armies. To the degree that the Iraqi army is Shia led, the Sunni Arabs will not cooperate or will join the enemy.

The present situation in Kurdistan is desperate.

Erbil has changed a lot since I was there last. In early 2013, on my way into Syrian Kurdistan, I had stopped off in the city for a few days to make preparations. Then, the city had the feel of a boom town shopping malls springing up across the skyline, brand new SUVs on the road, Exxon Mobil and Total were coming to town. It was the safest part of Iraq, an official of the Kurdish Regional Government had told me proudly over dinner in a garden restaurant.

A new kind of Middle East city.

What a difference a year makes. Now, Erbil is a city under siege. The closest lines of the Islamic State (IS) forces are 45 kilometers away. At the distant frontlines, IS (formerly ISIS) is dug in, its vehicles visible, waiting and glowering in the desert heat. The Kurdish Peshmerga forces are a few hundred meters away in positions hastily cut out of the sand to face the advancing jihadi fighters.

The problem and a solution are both clear. Obama is not serious about doing anything in Iraq or Syria and the Kurds may have to fend for themselves. Interesting enough, there are Jewish Kurds. Israel may have more at stake here than we do.

The phrase “Kurds have no friends but the mountains” was coined by Mullah Mustafa Barzani, the great and undisputed leader of the Kurdish people who fought all his life for Kurdish independence, and who was the first leader of the Kurdish autonomous region. His son, Massoud Barzani, is the current president of Iraqi Kurdistan. Other family members hold key positions in the government.

Perhaps the Israelis and Kurds can work out an alliance. The US, under Obama, is untrustworthy. We will see what happens.

The Yazidi minority we hear about in the news is not the only Kurdish minority. The Jews of Kurdistan, for example, maintained the traditions of ancient Judaism from the days of the Babylonian exile and the First Temple: they carried on the tradition of teaching the Oral Torah, and Aramaic remained the principal tongue of some in the Jewish Kurdish community since the Talmudic period. They preserved the legacy of the last prophets — whose grave markers constituted a significant part of community life — including the tomb of the prophet Jonah in Mosul, the prophet Nahum in Elkosh and the prophet Daniel in Kirkuk. When the vast majority of Kurdish Jews immigrated to Israel and adopted Hebrew as their first language, Aramaic ceased to exist as a living, spoken language. Although our grandparents’ generation still speaks it, along with a few Christian communities in Kurdistan, Aramaic has been declared a dead language by the academic world.

Israel might be an answer to the Kurds’ dilemma. I don’t think we are, except for supplying materials which we should have been doing all along.

Book Review: Menace in Europe, by Claire Berlinski

Menace in Europe: Why the Continent’s Crisis Is America’s, Too by Claire Berlinski

—-

I read this book shortly after it came out in 2006, and just re-read it in the light of the anti-Semitic ranting and violence which is now ranging across Europe. It is an important book, deserving of a wide readership.

The author’s preferred title was “Blackmailed by History,” but the publisher insisted on “Menace.” Whatever the title, the book is informative, thought-provoking, and disturbing. Berlinski is good at melding philosophical thinking with direct observation. She holds a doctorate in international relations from Oxford, and has lived and worked in Britain, France, and Turkey, among other countries. (Dr Berlinski, may I call you Claire?)

The book’s dark tour of Europe begins in the Netherlands, where the murder of film director Theo van Gogh by a radical Muslim upset at the content of a film was quickly followed by the cancellation of that movie’s planned appearance at a film festival–and where an artist’s street mural with the legend “Thou Shalt Not Kill” was destroyed by order of the mayor of Rotterdam, eager to avoid giving offense to Muslims. (“Self-Extinguishing Tolerance” is the title of the chapter on Holland.) Claire moves on to Britain and analyzes the reasons why Muslim immigrants there have much higher unemployment and lower levels of assimilation than do Muslim immigrants to the US, and also discusses the unhinged levels of anti-Americanism that she finds among British elites. (Novelist Margaret Drabble: “My anti-Americanism has become almost uncontrollable. It has possessed me, like a disease. It rises up in my throat like acid reflux…”) While there has always been a certain amount of anti-Americanism in Britain, the author notes that “traditionally, Britain’s anti-American elites have been vocal, but they have generally been marginalized as chattering donkeys” but that now, with 1.6 million Muslim immigrants in Britain (more worshippers at mosques than at the Church of England), the impact of these anti-Americans can be greatly amplified. (Today, there are apparently more British Muslims fighting for ISIS than serving in the British armed forces.)

One of the book’s most interesting chapters is centered around the French farmer and anti-globalization leader Jose Bove, whose philosophy Berlinski summarizes as “crop worship”….”European men and women still confront the same existential questions, the same suffering as everyone who has ever been born. They are suspicious now of the Church and of grand political ideologies, but they nonetheless yearn for the transcendent. And so they worship other things–crops, for example, which certain Europeans, like certain tribal animists, have come to regard with superstitious awe.”

The title of this chapter is “Black-Market Religion: The Nine Lives of Jose Bove,” and Berlinski sees the current Jose Bove as merely one in a long line of historical figures who hawked similar ideologies. They range from a man of unknown name born in Bourges circa AD 560, to Talchem of Antwerp in 1112, through Hans the Piper of Niklashausen in the late 1400s, and on to the “dreamy, gentle, and lunatic Cathars” of Languedoc and finally to Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Berlinski sees all these people as being basically Christian heretics, with multiple factors in common. They tend appeal to those whose status or economic position is threatened, and to link the economic anxieties of their followers with spiritual ones. Quite a few of them have been hermits at some stage in their lives. Most of them have been strongly anti-Semitic. And many of the “Boves” have been concerned deeply with purity…Bove coined the neologism malbouffe, which according to Google Translate means “junk food,” but Berlinski says that translation “does not capture the full horror of bad bouffe, with its intimation of contamination, pollution, poison.” She observes that “the passionate terror of malbouffe–well founded or not–is also no accident; it recalls the fanatic religious and ritualistic search for purity of the Middle Ages, ethnic purity included. The fear of poisoning was widespread among the millenarians…” (See also this interesting piece on environmentalist ritualism as a means of coping with anxiety and perceived disorder.)

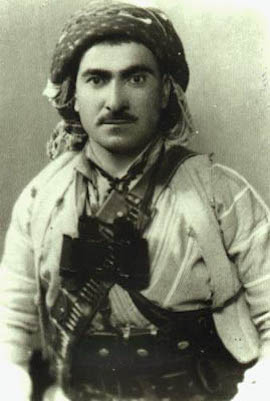

Barzani

Barzani